2016 has been a game changer in terms of redefining the global political and economic landscape. Rivers of ink are being spilled in trying to both politically and behaviorally analyze Trump’s recent victory in the U.S. presidential election. However, it has become clear that there remains limited ability among mainstream psephologists, or political scientists, to gauge the different degree of motivations underlying voting behavior among today’s voter class.

There is a tendency to over utilize the Rational Choice Theory, and assume all individual voters are “rational agents,” who make decisions to maximize their own self-interest. However, in Western discourse, recent political events, such as Trump’s victory in the United States and Brexit in the European Union (EU), indicate that individuals may not always vote rationally, but may vote under a level of bounded rationality. At the same time, identifying an economic explanation for the U.S. election for why voters preferred an authoritative, unconventional candidate like Trump can be instructive. The stagnation of real wages in the United States provides an explanation for the larger socio-economic issue: the increasingly discontented low-skilled labor force.

Increasing Productivity with Stagnating Wages

The recent rise of economic and political nationalism in countries like the United States and the United Kingdom, in addition to the rise of right-wing politics in other European countries, can be seen as a product of a “skills mismatch” and rising levels of educational disparity, together causing a persistent stagnation of productivity, wages, and employment opportunities for low-skilled workers.

These adverse effects of decreasing trade barriers, outsourced production, and capital mobility, are not a recent phenomenon. They are the basic intuitive idea behind the Stolper-Samuelson model. This model explains how opening trade between developed and developing nations can hurt unskilled workers in the developed nation. Developed nations with relative capital abundance will specialize in producing capital-abundant goods and import labor-abundant goods, thus decreasing the reliance on labor. This phenomenon can be seen in the United States and the United Kingdom, which are both relatively capital-abundant nations, which over the past few decades have specialized in capital-intense goods and have increasingly off-shored and out-sourced production of labor-intensive goods, like manufacturing. The move away from manufacturing and other labor intense industries has hurt the low-skilled worker class.

Countries in Eastern Europe have experienced similar issues, as explored by The Economist in an investigation of the “dark side of globalization.” Eastern Europe has seen increased globalization cause a rise in labor costs from bouts of foreign investment that have decreased upward social mobility, causing low-skilled workers and their real wages in these countries to be worse off than they were before the 2008 EU debt crisis.

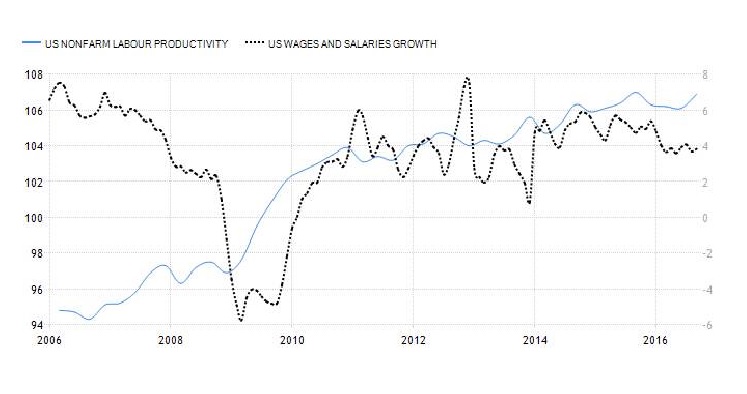

Figure 1: U.S. Nonfarm Labor Productivity vs. U.S. Wages and Salaries Growth

Source: Extractions from Trading Economics database

As evident from Figure 1, post the 2007-08 economic crisis, there was a sharp decline in both labor productivity and wages in the non-farm low-skilled sector across the United States. While labor productivity picked up in the quarters following the crisis, real wages grew much slower. According to a recent study, real wages per hour in the non-farm business sector were 0.5 percent lower 20 quarters, or six and a half years, after the start of the recovery.

What remains worrying is that over the last decade, mostly under the Obama administration, the rise in labor productivity during the recovery process has not caused real wages to proportionately rise at the same pace for the U.S. labor force.

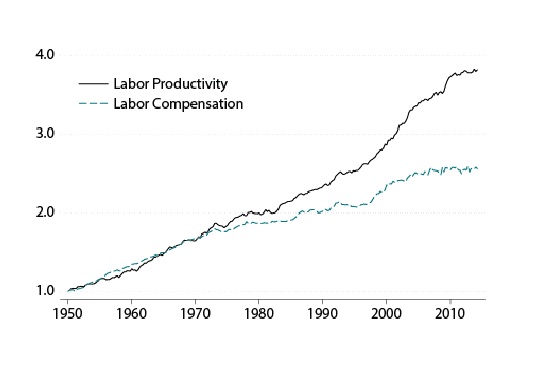

Figure 2: Labor Compensation and Productivity after the 2007-08 recession

Source: BLS Labor Productivity and Costs dataset for the nonfarm business sector

The wage stagnation for the non-farm, low-skilled base since the 2007-08 financial crisis is strongly related to the reduction of public spending on education at both the primary and university levels. The sharp reduction in public spending on education was due to budget cuts during the recession, and the rise of private schools and universities. However, these cuts have drastically hindered upward social mobility for the low-skilled labor base. Not only does the rise in private education further increase educational disparity, public schools also provide an important source of steady employment for the working class. Furthermore, although making budget cuts is the instinctual first move of state and local governments during times of recession, taking a neo-Keynesian approach of increasing public spending on social programs, like education, would have propped up the economy and provided employment.

In a series of research articles, The Economist analyzed the freeze in wages seen in the United States over the last decade and a half. Scholars including Dani Rodrik, Ha Joon Chang, Joseph Stiglitz, Raghuram Rajan, and Kaushik Basu have been talking about this phenomenon as well. Especially surprising is how the Hillary Clinton electoral campaign in particular did not gauge the level of discontent amongst low-skilled nonfarm workers, usually referenced as the white population who voted for Trump.

67 percent of non-college-educated whites, who make up most of the nonfarm, low-skilled labor base, voted for Trump, 72 percent of whom were men and 62 percent were women. The majority of white voters voted for Trump in the hope that he would “make America great again” by nurturing the manufacturing sector and restoring high-paying jobs while at the same time raising tariffs on goods imported from China. While the Democrats were conscious of the harmful effects of such trade policies, Hillary Clinton’s campaign was unable to convince the low-skilled labor force that her economic policies would increase wages and employment options.

Concluding Thoughts

Perhaps a more detailed empirical examination of economic trends in the United States over the last decade may shed more light on how a leader like Trump was voted into the White House. In times of looming political and economic uncertainty, there is also a need to revisit pre-existing political and economic analysis frameworks to allow for better policymaking.

An empirically tested, field-based, validated method for policy assessment will be most useful in depicting the reality on the ground to address intensifying socioeconomic problems. Having said that, in such transformative times where leaders like Trump are shifting the tectonic plates of politics, it will be hard to stay even cautiously optimistic for such methodological processes to be incorporated.

***

Image: Matt Johnson, Flickr