This comes quite late to the party. George Perkovich and Toby Dalton’s Not War, Not Peace?: Motivating Pakistan to Prevent Cross-Border Terrorism has been well-received by many of India’s strategic and security analysts through their reflections and reviews. The 300-page primer on India’s options to deal with Pakistan’s sponsorship of cross-border terrorism draws significantly from the authors’ interviews with Indian experts and officials (although most of the interviewees have not been named, the book is resplendent with incisive quotes). This way, the author-duo allows the Indian strategic community to be a discussant in the investigation rather than making this yet another American analysis of the India-Pakistan situation.

The central question addressed in the book is: how can India motivate Pakistan to prevent cross-border terrorism? The underlying research questions are more nuanced – how effective and feasible is the use of force or the threat of use of force by India against Pakistan? How can India minimize the risks of escalation (into a conventional war and eventually nuclear exchange) while pursuing strategies of deterrence and compellence with Pakistan? Three assumptions appear to inform the study: first, that the Pakistani state (especially the Pakistan Army and the Inter-Services Intelligence) lend support to anti-India terror groups; second, that the Pakistani security leadership makes a rational cost-benefit analysis of its use of proxy groups as a sub-conventional strategy to fight India; and third, that the onus of peace-making in the complex bilateral relationship lies with India. These assumptions, more than the assessment of India’s options and capabilities, are likely to stimulate a sense of comfort as well as discomfort to the Indian reader.

The authors suggest that in order to deal with cross-border terrorism, India has to not only deter Pakistan from supporting anti-India terror groups but also compel Pakistan to act to dissuade and dismantle such groups. The latter is obviously a more onerous task to execute for any Indian government, since India has found it difficult even to deter Pakistan. At the heart of the assessment, therefore, is a combination of deterrence and compellence strategies. Five “ideal type options” are discussed neatly in five separate chapters in the book: the Army-centric incursions (into Pakistani territory à la Cold Start), the limited airborne operations, covert operations, signalling and posturing through innovations in nuclear capabilities and doctrine (to complement the Army-centric and Air-Force led options) and non-violence compellence (which ranges from restraint to punishing Pakistan economically, politically and diplomatically). Each option is then weighed against the parameters of India’s military-technological capability and political will, likely consequences, and Pakistan’s response, escalation management, and damage limitation. While the Indian leadership would be likely to respond to a high-level terrorist attack in India by Pakistani-sponsored terror groups like the Jaish-e-Muhammad and the Lashkar-e-Taiba through symbolic airstrikes on terrorist-related targets and covert operations, it is argued that both options fair sub-optimally. The Air Force-led operations risk escalation to ground warfare. Besides, India’s fairly-known military and technological weaknesses take away significant mileage from this option. Throughout the book runs the theme of India’s operational intelligence problem, which makes any military strategy, especially covert operations, weak. In the overall assessment, the authors conclude then, almost predictably, that non-violent compellence is the least escalatory and most damage-limiting of the five options for India.

The book’s five-by-three matrix (five options versus three strategic objectives) risks being read as one which shows India to be weak in the face of Pakistan’s sponsorship of terrorism. The options are therefore posed not as alternatives but as a set of responses that would constitute a multi-pronged Indian strategy to deter and compel Pakistan to prevent cross-border terrorism. The matrix helps in understanding the prospects and dangers of escalation, particularly since the objective of escalation domination would guide any Indian military action once confrontations begin. And escalation would be “inevitable and unpredictable” as Ajai Shukla notes in his review of the military escalation ladder for cross-border operations. The strategy of non-violent compellence fares best as compared to the other four options not in terms of how close it gets to achieving the objective of stopping cross-border terrorism from Pakistan, but in terms of its low escalatory nature. Options like a naval blockade can arguably result into escalation, depending on the nature of the blockade and how Pakistan chooses to interpret it.

As India’s military and political leadership discuss options and strategy in the aftermath of the Pathankot, Pampore, and Uri attacks, there appears to be continued interest in maintaining strategic restraint. The question here is also whether any of these attacks constitutes as a “high profile” terrorist attack, as could be understood in the discussion about India’s response options. Polemics against Pakistan help the leadership to satisfy the domestic-psychological conscience but they would have to be supported by prudent strategies and capabilities. Security imperatives require that while India works on violent and non-violent coercive strategies vis-à-vis Pakistan, the fortification of defensive capabilities is indispensable.

Editor’s note: In this four-part series, SAV contributors Mayuri Mukherjee, Muhammad Faisal, Fahd Humayun, and Tanvi Kulkarni review authors George Perkovich and Toby Dalton‘s new book Not War, Not Peace?: Motivating Pakistan to Prevent Cross-Border Terrorism (Oxford University Press, 2016). Read the entire series here.

***

Image 1: Jack Zallium, Flickr

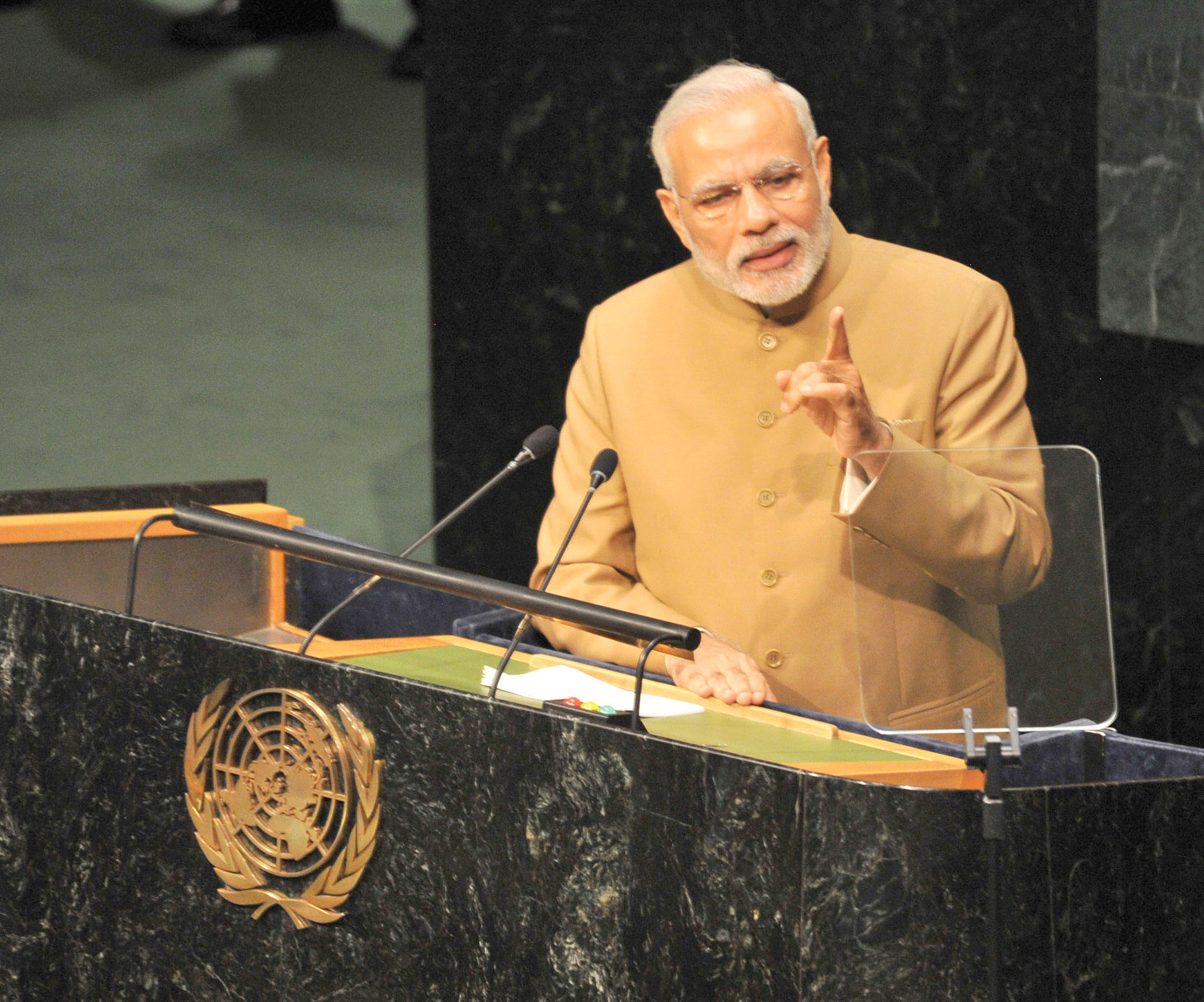

Image: Narendra Modi, Flickr