“We need to look at three things here: Getting more women to engage with foreign policy issues, reflect women’s interests in foreign policy, and bring in a feminist perspective to foreign policy.”

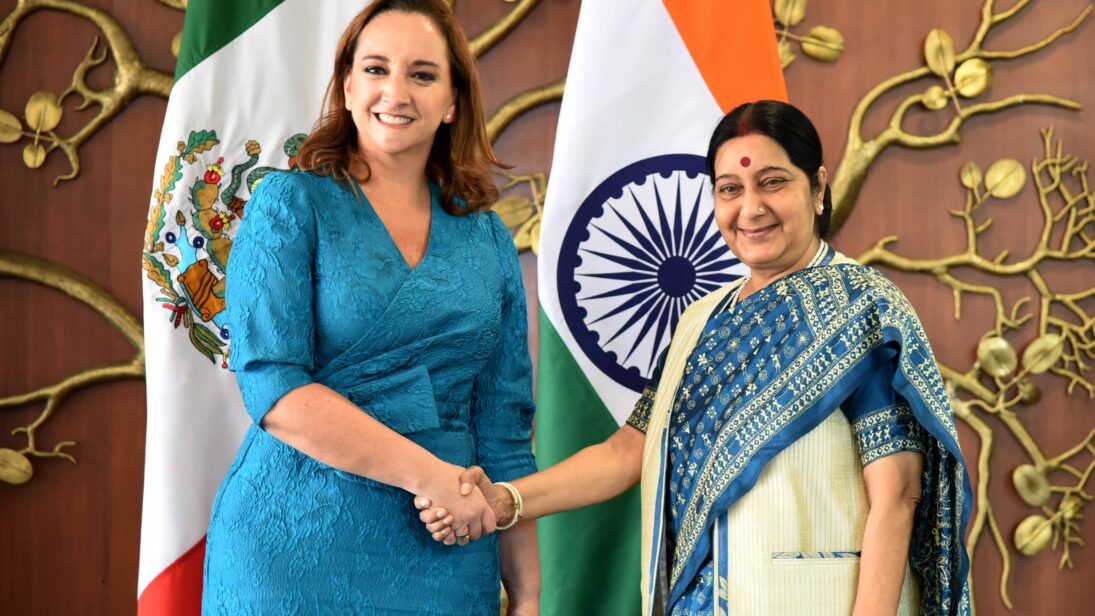

In a recent interview, India’s External Affairs Minister, Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, articulated the need for India to embrace a more gender-balanced foreign policy. But time and again, onlookers have raised concerns about what an Indian Feminist Foreign Policy (FFP) would look like. To mitigate these concerns, Indian leaders should apply lessons from Mexico’s implementation of a FFP. The two countries face similar development challenges and Mexico is the first country from the global south to adopt a FFP, suggesting that regardless of development barriers, any government can make commitments to ensuring tangible gender equality.

Mexico is a good point of comparison to India for several reasons. First, reform came slowly to Mexico, which, like India, houses a deeply patriarchal society. Second, both countries host massive income inequality and social stratification. Third, corruption and misogyny are so deeply embedded in the political settlements in India and Mexico that it is extremely difficult to bring any kind of transformation. India can successfully build from Mexico’s example by initiating affirmative measures to promote women’s participation, adopting a National Action Plan (NAP) on UNSCR 1325, and implementing cross-sectoral reforms to include gender issues in its policies.

Lessons from Mexico

Mexico’s FFP initiatives have focused on the creation of gender parity in its foreign and national policy mechanisms. As a result, the Mexican government has been enforcing policies aimed at improving female representation in all political spheres. These programs began in 2003 when Mexico introduced a 30 percent quota for women political party nominees. In 2014, Mexico mandated gender parity in its constitution to ensure that more female voices were represented in politics. The Mexican Foreign Relations Department committed in 2016 to the new batch of ambassadors including 50 percent women. Subsequently, the Mexican Senate in 2019 granted a 50 percent reservation for women in government positions.

India can successfully build from Mexico’s example by initiating affirmative measures to promote women’s participation, adopting a National Action Plan (NAP) on UNSCR 1325, and implementing cross-sectoral reforms to include gender issues in its policies.

In addition to these reforms, Mexico has also worked across sectors to engage women in issues—such as combating climate change, trade and immigration, and LGBTQ+ rights—that disproportionately affect women. For instance, Mexico in 2018 launched the “Pro-Equality” project to increase support for international women’s rights treaties and promote women’s participation. In 2019, Mexico pushed for the inclusion of a Gender Action Plan on Climate Policy at the UN Climate Change Conference by making a strong case for the interdependence of gender and climate policies. And, last year, Mexico adopted its first NAP for the implementation of UNSCR 1325, which incorporates gender discussions and women’s perspectives in its domestic policies.

These systematic efforts to include women have successfully improved the equal representation of men and women in law-making processes to bring about an equitable foreign policy. The Mexican government has become one of the most gender-equal in the world. Today, women hold 50 percent of seats in the Lower House of the Mexican Parliament and 49.22 percent in the Upper House. Nearly 56 percent of its Foreign Service is female, a substantial increase from 42.4 percent female staffers in 2015. And this increased gender equality manifests in Mexico’s foreign policy by ensuring that the attitudes and interests of Mexico’s women are well represented.

Applying Mexico’s Strategy to India

Parallel structural inequalities, masculinized political systems and socio-economic status suggest that similar reforms in India could yield successful FFP implementation. As in India, government corruption and persisting inequalities have exacerbated gender divisions. Adding on to this is the heavy patriarchal structure of both countries that allows for cultural norms to shape acceptable roles and behaviors for women.

A few decades ago, gender discussions were unthinkable in Mexico, stemming in large part from the “weight of the Catholic Church, patriarchy, and a conservative political class.” Many religious traditions in India reinforce harmful socio-cultural practices such as child marriage, dowry, female genital mutilation—all of which threaten gender equality.

And as both countries share a common vision of establishing a rules-based international order, India—following Mexico’s lead—should commit to a FFP by adopting reforms, a localized NAP, and a cross-sectoral gender approach. First, the Indian administration should consider applying affirmative action—such as reservations policies—that can pave the way for improving women’s access to political office and reducing statistical discrimination. These reservation policies could then help engender substantive equality, work towards dismantling structural inequalities and emphasize social human rights.

Additionally, India has not yet adopted a NAP on UNSCR 1325, which identifies priorities, responsibilities, resources, and initiate strategic actions that have an impact on its gender foreign agenda. Mexico’s case has revealed that a NAP can serve as an important instrument in aligning a country’s domestic goals with its FFP approach. Mexico in fact designed its NAP in a way that ensures the mainstreaming of gender issues into all areas of Mexican foreign policy. In this sense, India lacks a proper mechanism for guaranteeing women’s participation, protection, inclusion—all of which can be collectively addressed with a NAP. A NAP could also provide India with a detailed roadmap for meaningful transformation towards a more gender equal and peaceful society.

Finally, India’s efforts have remained limited in terms of initiating cross-sectoral policy reforms that are inclusive of gender. As such, the primary area where practitioners have considered gender in India’s foreign policy has been development assistance. And while development programs have had a positive impact on the lives of women around the globe, many have been designed in an ad-hoc manner, failing to address the root causes of gender inequality.

Mexico’s FFP has demonstrated that regardless of the patriarchal structure and low GDP, governments can and should make commitments to amplifying the voices of women. India can follow in Mexico’s stead.

Mexico, on the other hand, has been able to bring in more and more women in part because it has cautiously decided to work on many different policy issues through a gendered lens, gradually addressing persistent inequalities. For India, as female representation improves with reforms that deliberately work across sectors, policymaking is also likely to become more humane and gender-sensitive, protecting as well as upholding the rights of all.

Conclusion

Mexico’s FFP has demonstrated that regardless of the patriarchal structure and low GDP, governments can and should make commitments to amplifying the voices of women. India can follow in Mexico’s stead. But despite contextual similarities between the two countries, there is no guarantee that institutionalizing gender representation will yield the exact same results in India. Still, a FFP will only complement India’s current security policy—especially as it shores up its resources in its neighborhood—and orient its foreign policy in a more peaceful direction.

***