Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and U.S. President Joe Biden are looking forward to creating new horizons within their strategic partnership. Following Modi’s official state visit to Washington in June, the United States and India listed several new areas for cooperation but missed one critical opportunity: the agricultural sector. Within the context of the G-20 resolution to strengthen cooperation on food security and nutrition, strengthening U.S.-India cooperation in agriculture will support resilience in the global food supply chain, help combat China’s growing agricultural footprint, revitalize India’s struggling agricultural sector, and deaccelerate agro-induced climate change.

Incentives for U.S.-India Agricultural Cooperation

Correcting the Hazards of the Green Revolution

On the wider spectrum of bilateral cooperation between the United States and India, the agricultural sector has often been sidetracked, and the discussion on reform remains contentious on some multilateral forums. For instance, the United States believes that agricultural subsidies provided by India to its farmers violate the World Trade Organization’s norms. However, both countries have recently agreed to resolve some trade tariff-related issues within the WTO. Furthermore, the United States’ decision during the Trump Administration to push India out of the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) negatively impacted the prospects of agricultural cooperation.

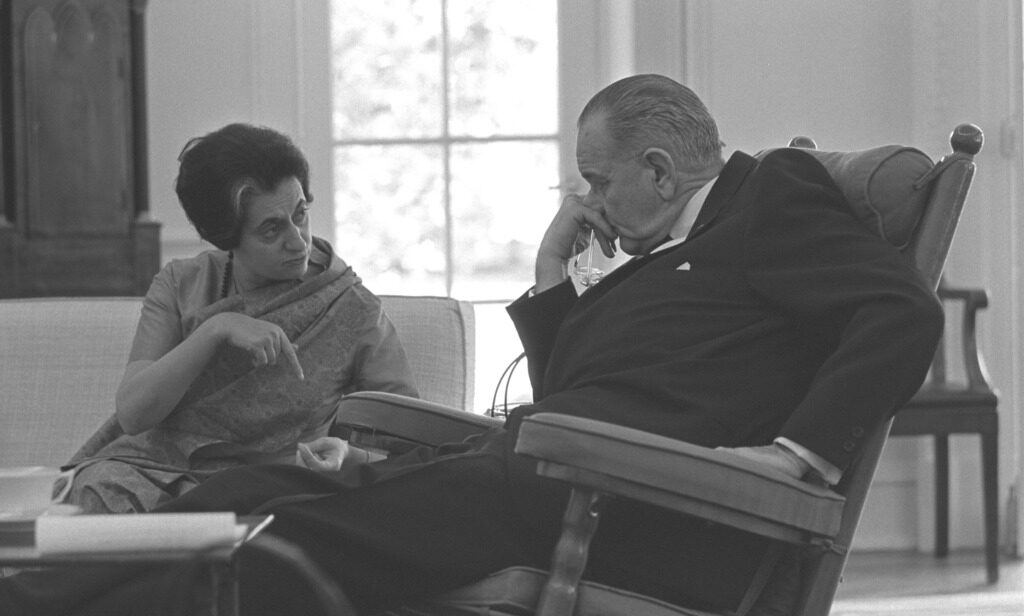

However, despite recent developments, the United States and India have had a unique historical record of agricultural cooperation. The United States revolutionized India’s agricultural sector through the Green Revolution in the 1950s and 1960s, which pioneered research on high yielding varieties of seeds and temporarily relieved India of its food crisis. However, the Green Revolution was uneven, incomplete, and limited, and created further challenges such as ecological imbalances, internal migration, and health hazards due to the limited geographical reach and inadequate implementation of market reforms. This historical precedent provides the United States a key rationale to initiate structural reforms in India’s agricultural sector to complete and correct the work it began in the 1960s.

However, the Green Revolution was uneven, incomplete, and limited, and created further challenges such as ecological imbalances, internal migration, and health hazards due to the limited geographical reach and inadequate implementation of market reforms.

Strengthening Global Food Supply Chains

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has disrupted the global food supply chain, already strained by the COVID-19 crisis. Given that both countries are net exporters of essential agricultural products and fertilizers, the war has increased food insecurity in poorer and more vulnerable countries in Asia and Africa. For instance, Egypt, Benin, and Somalia are heavily dependent on wheat imports from Ukraine and Russia. A study suggests that more than 47 million people may suffer from acute food shortages due to the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict. This will increase the bar of global hunger and malnutrition. Russia is also a global hub of fertilizer supply for upholding global food production. In this way, the conflict is adversely impacting the global food value chain from farmers to consumers, including the Indian farm sector.

Countering Beijing’s Agricultural Footprint

India’s gross cropland is 32 million hectares (mha) more than China’s total cropland. Despite this, the value of Chinese agricultural production is three times more than India’s. Some studies suggest that despite evolving from similar conditions, Chinese agricultural productivity is 50 to 100 percent higher than Indian output. A key reason for this disparity is the lack of adequate agricultural reforms in India since 1991. India’s investment in agriculture is almost six times less than China’s investment in the same.

From 2020 to 2023, there was a sharp fall in India’s cereal exports to China because of market access issues. This has created an overall trade deficit between the two countries of USD $73.31 billion in 2021-22. However, experts believe that despite the ongoing border conflict with China, India is eager to export food grains to China as ‘a strategic act’ to reduce its trade deficit with its neighbor. Meanwhile, China has charted out a plan for enhancing cooperation with its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) partners in the agricultural sector to meet its food security concerns. Furthermore, this year, China has chosen ‘Agricultural Development and Food Security’ as the theme to mark the 30th Anniversary of China-ASEAN cooperation. In Southern Asia, China is also exploring possibilities to modernize the agricultural sectors of its allies, including Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. Countering growing Chinese dominance in the Asian food market requires a collaborative Indo-U.S. effort.

The Need for Indian Agricultural Reforms

China has carried out focused agricultural reforms since the 1970s to accelerate growth, reduce poverty, and mobilize surplus labor towards the manufacturing sector. On the contrary, India’s agricultural sector engages more than 45 percent of the workforce, but the share of agricultural contribution to India’s GDP is only 18.3 percent. As per official sources, the declining share is ‘due to structural changes in the economy and more employment opportunities coming up in new areas’. In reality, the structural reforms have not only inadequately mobilized the workforce to other sectors but have also been insufficient to increase agricultural productivity.

The 2022-23 budget stated that the government will use the help of new start-ups, the banking sector, investors, universities, and research centers to revive the agriculture sector. However, most of these plans need U.S. support to finance agricultural start-ups, facilitate Indian products in the international market, and share modern agricultural practices. Without this, Indian agricultural productivity would be low despite its surplus labor.

The absence of newer climate-friendly technologies, the sustained use of traditional methods of cultivation and animal husbandry, and increasing deforestation are accelerating climate change in India.

Achieving Joint Climate Goals

The agriculture sector is a key source of the climate problem in India. Various studies suggest that agriculture-related activities contribute a third of total greenhouse gas emissions at the global level. The absence of newer climate-friendly technologies, the sustained use of traditional methods of cultivation and animal husbandry, and increasing deforestation are accelerating climate change in India. Additionally, increasing food spoilage, loss, and wastage intensifies environmental stress.

The 2023 Indian Economic Survey underlines the fact that the Indian agricultural sector needs technological advancements to combat the adverse impacts of climate change. However, India does not have sufficient technological capabilities to achieve the goals of climate-smart agriculture (CSA), and, therefore, needs a multi-pronged strategy for technology and knowledge transfer from the United States. U.S. support can reorient India’s traditional farming practices, while also diversifying its crop production and investing in better monitoring and weather forecasting systems. However, the U.S.-India Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology’s (iCET) scope has not been expanded to these dimensions.

A Way Forward

During the 13th Ministerial-level meeting of the India-United States Trade Policy Forum (TPF), both countries agreed to increase dialogue on food and agricultural trade. This group has played an instrumental role in resolving some issues related to agro-trade, but their cooperation in facilitating agricultural reforms and enabling the fulfillment of CSA goals remains limited. For instance, without re-admitting India into the GSP list, both countries may not be able to open new avenues for Indian agricultural products. At the same time, it is hard to imagine significant agricultural reforms in India without extensive support from the United States to develop agricultural infrastructure and improve financial and insurance systems for technological development. Expanding the scope of iCET to include the agriculture sector could be a lead move.

Moreover, facilitating Indian agricultural reforms would not only improve India’s domestic resilience but would also resolve many issues related to the global food supply chain. As per the Global Food Policy Report 2022, increasing climate change and overreliance on traditional patterns of agriculture are disrupting the global food supply chain. Thus, both partners need to widen and accelerate cooperation in the agriculture sector through community consultation for adopting the best agriculture governing practices to make the industry profitable for farmers, cost-effective and nutritious for consumers, and environmentally sustainable.

Also Read: Bangladesh is Forging Ahead with a Green Foreign Policy

***

Image 1: Indira Gandhi meeting Lyndon B. Johnson via Wikimedia Commons

Image 2: A farmer in Bihar, India via Flickr