For the past few months, tens of thousands of farmers primarily from India’s agriculture-dependent northwestern states of Punjab and Haryana have gathered on the outskirts of New Delhi to protest three recently passed farm laws. The protests represent a serious challenge to the Modi government given the dire consequences of being seen as hostile to the interests of farmers in a country where more than half the population earns its living through agriculture. In the midst of this charged scenario, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s comments expressing support for the farmers resulted in a diplomatic spat between the two nations, with the Indian establishment warning Canada of damaging consequences to the relationship. Trudeau’s comments also sparked solidarity rallies and marches in Canada to protest the new agriculture bills.

Trudeau’s comments and India’s response underscore a pattern of domestic political concerns entering the bilateral relationship, which has long been overshadowed by what India views as Canadian sympathies for Sikh separatists in its diaspora population. Despite the relationship’s potential in the realms of trade, energy, and cooperating towards a multipolar Indo-Pacific, this most recent diplomatic quarrel once again raises the question of whether India-Canada ties can move past Sikh diaspora concerns. To do this, the internal politics of both countries will need to put the relationship above partisan considerations for narrow political gains.

Why is India Irked?

On the surface, Trudeau is well within his right in speaking up for the democratic rights of citizens globally and supporting the just cause of peaceful protest. Engaging with and looking after the Sikh community that forms part of his constituency and continues to have stakes in India’s Punjab is a natural course of action for any democratic leader. The root of India’s resentment, however, lies in its troubling history of Sikh separatism and the perceived support that Canadian politicians continue to lend to the Khalistan movement.

Demands for an independent and separate state called Khalistan for Indian Sikhs in Punjab led to over a decade of violence that killed thousands in the 1980s and early 1990s. Among the starkest public memories of this violence include the 1984 Golden Temple raid, the assassination of India’s Prime Minister Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards, the 1984 anti-Sikh riots, and the Air India flight terrorist attack that killed all 329 passengers on board.

The root of India’s resentment, however, lies in its troubling history of Sikh separatism and the perceived support that Canadian politicians continue to lend to the Khalistan movement.

Despite the challenges of managing India’s distinct diversity, the Indian Union has successfully thrived under a strong overarching Indian national identity. For a country whose current integrity, as Grant Wyeth puts it, is “reliant on a compact of pluralism,” separatist diaspora movements, despite limited traction for the same within India’s borders, threaten the core of India’s unity—something New Delhi is particularly sensitive to given the historic memory of a violent partition, the fallout of which continues today in the form of cross-border terrorism emanating from Pakistan.

While the Sikh separatist movement has been almost irrelevant in India since the mid-1990s, with Sikhs well integrated into India’s political mainstream, it continues to gain traction in Canada, albeit amongst only a small but vocal minority. In the 1960s, small sections of the Sikh diaspora in the United Kingdom, United States, and Canada also played a role in calls for an independent Khalistan and the later insurgency by offering crucial financial and political support. As detailed in a Macdonald-Laurier Institute report by veteran journalist Terry Milewski, Sikh separatists in Canada have received funding and support from Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence.

The Khalistan issue has previously trailed and disrupted efforts to improve India-Canada relations. Despite clumsy attempts to woo Indians with Punjabi dance moves and attire, Trudeau’s Liberal Party’s perceived association with Sikh separatists dominated coverage of his maiden 2018 India visit, so much so that Trudeau had to validate his support for a united India. In 2017, India objected to Trudeau’s presence at a Khalsa Day parade in Canada, which featured effigies of Sikh separatists amidst calls for a separate Khalistan. Such parades were cautiously avoided by Canada’s previous Prime Minister Stephen Harper to respect Indian sensitivities. Indian officials have also been denied entry into Canadian gurudwaras (Sikh places of worship), with no action taken by the Canadian government.

Building Domestic Support

There are about half a million Sikhs in Canada, constituting only 1.4 percent of the country’s population, however, Sikhs also represent an established, politically active, and coveted voting bloc in Canadian politics. Sikhs make up approximately five percent of the Canadian parliament and 12 percent of Trudeau’s cabinet. Punjabi origin MPs more than doubled in the Canadian Parliament from eight to eighteen in the 2015 elections. It is not surprising then that vote bank considerations and playing to a domestic constituency of Canadian Sikhs – many of whom maintain close links with Punjab and still have families and agricultural lands there – remains an important part of Trudeau’s agenda.

Although Trudeau did reject the “Referendum 2020” vote on a separate state of Khalistan organized by the U.S.-based Sikhs for Justice group, shoring up Sikh support has become all the more important. In January 2021, for instance, Trudeau’s Liberal Party ousted parlimentarian Ramesh Sangha, who allegedly accused the Party of pandering to Sikh separatists and derailing India-Canada relations. Trudeau’s minority government has also faced challenges from Sikh opposition leader Jagmeet Singh – who heads Canada’s New Democratic Party (NDP) and has been referred to as a Khalistan sympathizer by Punjab Chief Minister Amarinder Singh. Although the NDP only won 24 seats in Canada’s 2019 elections (as compared to 157 by Trudeau’s Liberal party), the results were still a strong showing compared to the NDPs performance in 2015 and Singh has drawn attention as a rising political figure for his prominent role in revitalizing the party. Singh also recently created an online petition urging Trudeau to condemn violence against farmers in India.

However, it is not just Canadian politicians who are guilty of prioritizing domestic optics over bilateral relations. The Khalistan bogey has also been exploited by Indian leaders for personal vendetta, as in Captain Amarinder Singh’s dubbing Canadian defense minister Harjit Singh Sajjan and three other cabinet ministers as “Khalistan sympathizers,” after Canadian authorities prevented Amarinder from visiting Canada before the 2016 Punjab assembly elections on legal grounds of barring political canvassing by foreigners. Further, Indian politicians have thrived on painting popular protest as existential threats to India’s unity, thereby polarizing the populace and cementing their support base by propagating a “nation under siege” mentality.

Can India-Canada Relations Move Beyond the Sikh Separatism Issue?

India-Canada ties have historically lacked a strong strategic component as neither prioritizes the other. For India, the major powers and its neighborhood take precedence especially when it comes to dealing with China, and Canada has historically prioritized relations with the United States and Europe. However, as middle powers see value in banding together in the context of heightened U.S.-China competition and the balance of power shifts to Asia; Canada too is increasingly engaging with Asia, for instance through its cooperation with the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), and its interest in the East Asia Summit (EAS). India, as an important rising Asian power, cannot be overlooked.

There is potential for these two vibrant, English-speaking democracies and G20 states to build on existing convergences. Both countries vie for a multipolar Indo-Pacific, and are looking to diversify their business supply chains. There is significant untapped potential in trade and energy as India exports to Canada accounted for only USD $2.9 billion in 2019; and, despite India’s uranium procurements from Canadian company Cameco, there is room for more substantial energy cooperation given India’s burgeoning energy needs and Canada’s oil and gas reserves. A 2020 report by the Canadian think tank the Asia Pacific Foundation also indicates that a growing number of Canadians support cooperation amidst rising concerns over China’s economic clout in the region.

As middle powers see value in banding together in the context of heightened U.S.-China competition and the balance of power shifts to Asia; Canada too is increasingly engaging with Asia…India, as an important rising Asian power, cannot be overlooked.

India has also played an important role in Canada’s COVID-19 vaccine procurement process, with Canada purchasing two million vaccine doses from the Serum Institute of India. This came soon after internal criticism of Canada’s slow vaccine procurement led to questions about whether Canada’s comments on the farmers protests impacted its ability to procure vaccines from India especially in light of India’s rigorous vaccine diplomacy.

Yet unless Canadian governments rethink their pandering to fringe elements for political gains and instead view India through a broader lens beyond the prism of its Sikh diaspora, it will be difficult for the relationship to transcend the Khalistan issue. India has recent memories of Khalistan separatism and those memories remain a part of its sensitivities towards Canadian politics. As researcher Karthik Nachiappan states, “Ottawa should think broadly, not purely in terms of votes and dollars.” On India’s part, it should remember that certain Indian ministers themselves played the Khalistan bogey to delegitimize the ongoing farmer protests. If India expects others to be sensitive to its history, it should reconsider dredging up long-buried ghosts of its past for narrow partisan gains. Instead, it can do with paying better heed to peaceful dissent within its borders.

***

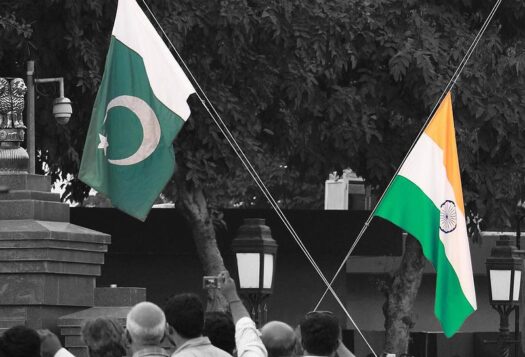

Image 1: Ministry of External Affairs, India via Flickr

Image 2: PRAKASH SINGH/AFP via Getty Images