Sri Lanka’s strategic location in the Indian Ocean has long been touted as an asset that could transform the island nation into a regional trading hub. Adjacent to Indo-Pacific shipping routes, Sri Lanka is located in one of the fastest growing sub-regions in the world. However, due to a combination of history and economics, Sri Lanka now finds itself caught between an ongoing geo-strategic battle between China and India. While India has historically enjoyed considerable influence over Sri Lankan affairs, China’s growing engagement and investment in Sri Lanka could undermine that influence in time. China’s role in Sri Lanka’s economic rebirth after Sri Lanka’s 25-year civil war underscores this point. However, the success of Sri Lanka’s strategic interests and economic growth likely depends on maintaining harmonious relations via “strategic promiscuity” between China and India.

Filling a Vacuum

China’s economic and strategic interest in Sri Lanka emerged as a result of the void created by India and Western developed economies. As countries like the United States ended direct military aid to the Sri Lankan government following allegations of human rights abuses in Sri Lanka’s civil war, China “leapt into the breach.” For example, even as the United States withdrew military aid in 2007, Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa signed a $37 million dollar deal for Chinese ammunition, ordinance, fighter jets, and anti-aircraft guns. That same year, Sri Lanka leased land to a Chinese consortium to construct the one billion dollar Hambantota deep-water port.

Moreover, in the immediate aftermath of the war, the Rajapaksa administration relied on Chinese support to shield Sri Lanka from international pressure regarding allegations of human rights violations in the United Nations Security Council and the UN Human Rights Council. Meanwhile, the Indian government faced significant pressure from its southern electorate to take a hard line against the Sri Lankan state. As Indian and Western support and influence dwindled, Colombo seized the opportunity to forge a stronger political relationship with China.

This political support eventually translated into deep economic engagement. In the aftermath of the war, China provided crucial monetary support to Sri Lanka. Chinese loans funded several important infrastructure projects across Sri Lanka, including a new expressway between Colombo and the Katunayake international airport, Hambantota Port, and Mattala Airport. As per a 2014 estimate, 70 percent of Sri Lankan infrastructure projects were funded by Chinese banks. Offering loans and other forms of assistance with few conditions, China positioned itself as the lynchpin of Sri Lanka’s economic growth, though some within Sri Lanka worry about an over-reliance on the Asian giant.

Debt and Development

While China has been instrumental in Sri Lanka’s post-war development, external debt has become a major economic concern. Sri Lanka’s external debt rose from $10.6 billion dollars in 2006 to $25.3 billion in 2016, amounting to 34 percent of Sri Lanka’s gross domestic product. Approximately 13 percent ($3.3 billion dollars) is owned by China. This debt has allowed China an even greater opportunity to strengthen its role in Sri Lanka as the island seeks to liquidate assets to offset its debt burden. For example, a recent agreement, worth $1.1 billion dollars, grants China a 70 percent stake in Hambantota port with a 99-year lease. In addition to operational control of the port, the agreement also includes the creation of a special industrial zone spanning 15,000 acres.

China has also become a prominent investor in Sri Lanka, especially in the tourism and construction sectors. In 2005, annual foreign direct investment into Sri Lanka from China totaled just under one million dollars; this figure has risen to $400 million as of 2014.

A vast amount of this investment has come in the form of the controversial Colombo Port City project, now renamed as the Colombo International Financial Centre. In addition to allegations of mass corruption and environmental concerns, the project has been viewed in some quarters as a threat to Sri Lankan sovereignty. Namely, the financial district would have granted China 50 hectares of land on a permanent, freehold basis. The current government, however, renegotiated the agreement down to 20 hectares on a 99-year extendable lease rather than full Chinese ownership. This renegotiation appeased sovereignty and security concerns domestically as well as among international partners, particularly India.

Balancing Indo-Chinese Interests

China’s economic activities have caused much consternation in India, but strategic issues also loom large in New Delhi’s mind. One such strategic concern centers around China’s possible use of Sri Lanka as a naval base. In 2014, the docking of two Chinese submarines in Colombo Port underscored this concern. Since then, however, Sri Lanka has been careful to allay Indian fears, even going so far as to reject a Chinese request to dock a submarine in May this year.

In addition, Sri Lanka has also taken proactive steps to balance its engagements with China with similar commercial opportunities for Indian investors. This year, Sri Lanka and India agreed to pursue a joint venture to redevelop and operate an oil storage facility in Trincomalee. Likewise, Sri Lanka is currently negotiating free trade agreements with India and China.

Conclusion

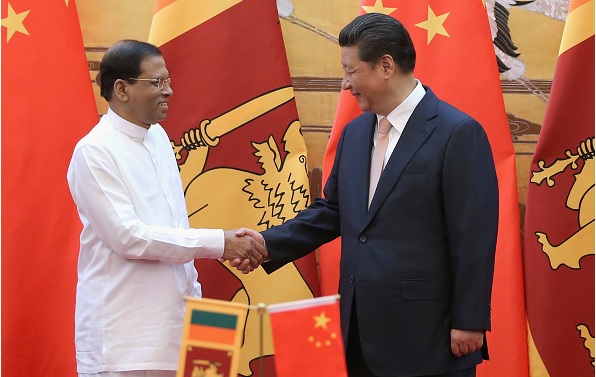

Consequently, rather than firmly aligning with either China or India, Sri Lanka is currently practicing a form of “strategic promiscuity.” In response to domestic pushback against growing Chinese influence in Sri Lanka and the political stance of the current Maithripala Sirisena government, China has been willing to compromise on its own interests for now. In the meantime, India may seek to reinvigorate its relations with its island neighbor and woo Sri Lanka back to its traditional sphere of influence. As long as Sri Lanka can find common ground with both China and India, especially economically, it can reap the benefits of having strong relations with both countries while preventing fallout from favoring one country over the other.

Editor’s note: This is the fourth installment of South Asian Voices’ new six-part series, China in South Asia. In this series, our contributors Fatima Raza from Pakistan, Saimum Parvez from Bangladesh, Avasna Pandey from Nepal, Kithmina Hewage from Sri Lanka, Ahmad Shah Angar from Afghanistan, and Pushan Das from India explore China’s strategic and economic goals in their respective countries, the challenges China may face in implementing those goals, and how China’s engagement will affect the regional balance of power in South Asia. Read the entire series here.

***

Image 1: Dhammika Heenpella via Flickr.

Image 2: Feng Li-Poo, Getty Images