When Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi ordered a 21-day national lockdown on March 25 to fight the spread of the coronavirus, the people of Kashmir were not fazed. The COVID-19 lockdown was essentially an extension of the months-long restrictions put in place by the central government last August when Article 370, which granted Jammu & Kashmir (J&K) a degree of regional autonomy within the Indian Union, was withdrawn. Thus, to Kashmiris, the national lockdown did not seem that different from their prevailing state of affairs.

Yet this isolation has not protected J&K from the spread of the coronavirus. Over 650 COVID-19 cases have been reported as of May 2, a significant number for a population of 12.5 million. Tens of thousands have been placed under quarantine. J&K reported its first case in mid March when a woman from downtown Srinagar who had just returned from Umrah (a shorter pilgrimage to Mecca) was found to be COVID-19 positive. Although she has since recovered, the number of cases accelerated after a religious leader from the city’s uptown area was diagnosed with the virus. He, along with an unspecified number of clerics, had returned from attending a Tablighi Jamaat gathering in New Delhi and visited some mosques in Kashmir. He later died and four of his contacts were also found to be infected.

But even as the number of people testing positive for the coronavirus continues to rise in J&K, the residual restrictions from the post-Article 370 shutdown continue to be in place, negatively impacting the pandemic response as well as intensifying the existing conflict.

Communication Restrictions Remain

Even as the number of people testing positive for the coronavirus continues to rise in J&K, the residual restrictions from the post-Article 370 shutdown continue to be in place, negatively impacting the pandemic response as well as intensifying the existing conflict.

After enforcing a total communications blackout across the Valley following the withdrawal of Article 370 last August, the government has yet to restore high-speed mobile internet for the general population. It took the government six months after the August move to open up 2G internet and seven months to restore fixed-line internet, but it has yet to restart 4G services. Similarly, access to social media has also only recently been restored. Citing the potential “misuse” of high-speed internet, the government has justified the ban on 4G on security grounds, saying it is “in the interest of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the state and for maintaining public order.”

However, the continued internet restrictions have denied the population of Kashmir easy access to necessary information on how to combat the spread of COVID-19. With only 2G speeds, it remains a time-consuming process for doctors to download important guidelines, such as from the World Health Organization, on preventing the spread of the virus, while conducting appointments over video is all but impossible. Further, for the section of society that cannot read or write, videos are essential for information sharing, but these cannot be streamed with restrictions on internet speeds. There are implications beyond healthcare as well, with the continued internet restrictions impacting students who need to attend classes online or those who need to work from home.

A Heavy-Handed Pandemic Response

While it is true that COVID-19 requires some stringent measures to combat it, New Delhi’s fight against the virus is melding with its counterinsurgency measures. This securitized approach to a public health crisis has the potential to exacerbate the conflict in Kashmir.

In recent days, many videos have circulated online of police beating people out on the roads for violating lockdown orders. As of March 29, 337 FIRs have been lodged against those defying the lockdown and 627 have been arrested, while 118 shops and 490 vehicles have been seized. In addition, police are reportedly using ground and cyber surveillance to track down those with recent history of travel as well as utilizing GPS information, in order to decide who needs to be quarantined. Citizens are also encouraged to keep tabs on their neighbors and inform the authorities if they know of anyone who has returned from travel outside the region or abroad. However, given the history of police and army excesses in Kashmir, there are apprehensions that in the garb of tracking suspected COVID-19 cases, authorities are also monitoring those deemed as security threats. Such heavy-handed tactics suggests that the government is treating a health emergency as a law and order problem, turning the fight against coronavirus into a security operation, which has struck fear into people rather than offer a sense of safety and assurance.

Moreover, even though former chief ministers Farooq Abdullah and Omar Abdullah have been released, the government has continued to detain many Kashmiri leaders despite calls for their release in view of the ongoing pandemic. These include former chief minister Mehbooba Mufti, former minister in the Peoples Democratic Party-Bharatiya Janata Party coalition Sajjad Gani Lone, and bureaucrat-turned-politician Shah Faesal, These senior leaders and politicians know the region well and enjoy a good rapport with people. They could have been involved in preventive action such as generating awareness about the virus and issuing appeals to citizens to stay indoors, lending a humane face to the severe measures to contain COVID-19. However, the government has inexplicably balked at letting them play such a role.

Meanwhile, the administration is struggling to cope with the growing number of infections in the region. Estimates suggest that the Kashmir Valley has less than 100 ventilators and only 85 ICU beds. In addition, doctors have raised concerns over the shortage of medical supplies such as personal protect equipment. Such meager resources can hardly accommodate the expected growth in the number of COVID-19 patients. Like elsewhere in India, the virus was initially spread by residents with a recent history of travel, but the fast increasing number of cases indicates that community transmission may have taken place. And while the government has announced a relief package for different categories of workers, more needs to be done to ramp up healthcare facilities. Instead of focusing on a strict enforcement of the lockdown, the priority must be to ensure that Kashmir’s fragile medical infrastructure is not overwhelmed and that the virus can be effectively contained.

COVID-19 and Ongoing Political Conflict

Intermittent clashes along the LoC in the past few weeks and their potential to escalate into a greater conflict between India and Pakistan as well as increased militant activity threaten to draw attention away from, or even disrupt, the fight against COVID-19 in J&K.

It was expected that with the enormity of the health crisis facing the region in light of COVID-19, the ongoing political conflict in J&K would be relegated to the background, with both the central government and the local administration focusing on containing the spread of the virus. But not quite. In the middle of efforts to deal with the pandemic, on April 1, New Delhi slipped in a new domicile law that entitles anyone who has stayed in J&K for 15 years to domicile status—enabling him or her to buy land and apply for local jobs. Conditions are more lenient for central government officials and students, who require a residence record of ten and seven years respectively.

The law, which is being seen in the Valley as geared towards altering the region’s demography, has brought the conflict back into the picture. There is now public pressure on leaders to react to this perceived onslaught, particularly National Conference leaders Farooq Abdullah and Omar Abdullah. Omar has called the domicile order an insult upon injury whereas separatist Hurriyat leader Syed Ali Shah Geelani has warned people against selling their land to outsiders, stating “the people of Jammu and Kashmir must not accept this domicile law and must fight tooth and nail against the plans of our occupier who wants to make us aliens in our own land.” While the COVID-19 lockdown may temporarily deter a visible expression of public resentment over this order, it is likely to sharpen the grievances of Kashmiris towards the state.

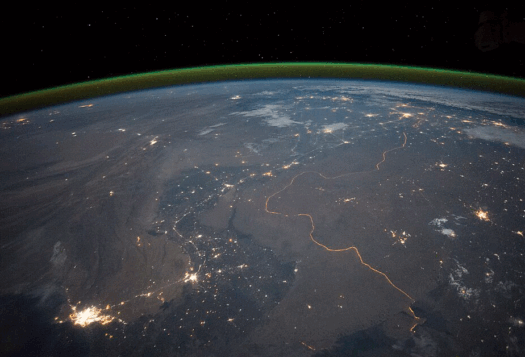

Meanwhile, militant violence and cross-border shelling have continued unhindered along the Line of Control. In an encounter in Keran sector in the first week of April, five Indian soldiers and five militants were killed while a heavy cross-border exchange took place between India and Pakistan along the border on April 12. Most recently, an encounter operation by the Indian military in Handwara in North Kashmir led to the death of five security personnel and two militants. Intermittent clashes along the LoC in the past few weeks and their potential to escalate into a greater conflict between India and Pakistan as well as increased militant activity threaten to draw attention away from, or even disrupt, the fight against COVID-19 in J&K.

There may be no break from violence for Kashmir even during a pandemic, and it remains to be seen how the government balances its response between addressing security threats and containing the spread of the virus.

***

Image 1: Tauseef Mustafa/AFP via Getty Images

Image 2: Tauseef Mustafa/AFP via Getty Images