After the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) lost its single-party majority in the recently concluded Lok Sabha elections in India, some analysts argued that the BJP’s loss of seats was driven by economic concerns — especially, high unemployment. For the new government, therefore, managing the economy and creating jobs will be the primary challenge, and this has in turn reignited a wider debate on the best developmental model for job creation in the country. Some experts argue that India would be best served by relying on high-skilled services, given the current state of the global economy. But others have championed the more traditional manufacturing-driven growth model. Given its geopolitical goals and decarbonization needs, India would need to invest more heavily in the latter.

High-Skilled Services or Low-Skilled Manufacturing?

While India has generally enjoyed robust growth in recent years, high unemployment remains a key impediment for the country in maximizing its demographic dividend. According to various estimates, India needs to generate between 12 million and 16 million jobs a year over this decade to absorb new entrants to the labor market. Agriculture continues to employ over 40 percent of the labor force, but given low productivity in the sector, agricultural workers still only generate 16 percent of GDP. Surplus labor from agriculture needs to be shifted to the manufacturing and service sectors.

In their new book, Breaking the Mould: Reimagining India’s Economic Future, economists Raghuram Rajan and Rohit Lamba argue that in the contemporary age, low-skilled manufacturing does not represent the best path for India to transition to a high-income country. According to Rajan and Lamba, the service sector has historically absorbed a larger share of those moving away from agriculture, while the share of jobs in manufacturing has stayed constant. They argue that in the present context, Indian firms will be further unable to generate jobs or sufficient profit margins because Indian labor tends to be relatively costlier than labor in Bangladesh or Vietnam. Moreover, even if India was to be successful in scaling up manufacturing, its ability to become yet another exporting power like China would be limited by growing protectionism against merchandise goods around the world. As a result, Rajan and Lamba assert that an export model led by high-skilled services would be a better bet for India. They counsel the government to build on the competitive edge generated by India’s massive population of English speakers and invest in education and skill-building.

Surplus labor from agriculture needs to be shifted to the manufacturing and service sectors.

Despite this logic, however, a growth model based on the export of services may not generate sufficient jobs for India’s large and relatively unskilled workforce that is bereft of decent higher education. In 2023, services exports only made up 25 percent of global trade. On the other hand, as developing countries improve their purchasing power, some analysts believe that demand for manufactured goods will increase in the years ahead, providing India with an opportunity to tap into these emerging markets. Under these circumstances, India cannot avoid investing in the manufacturing sector.

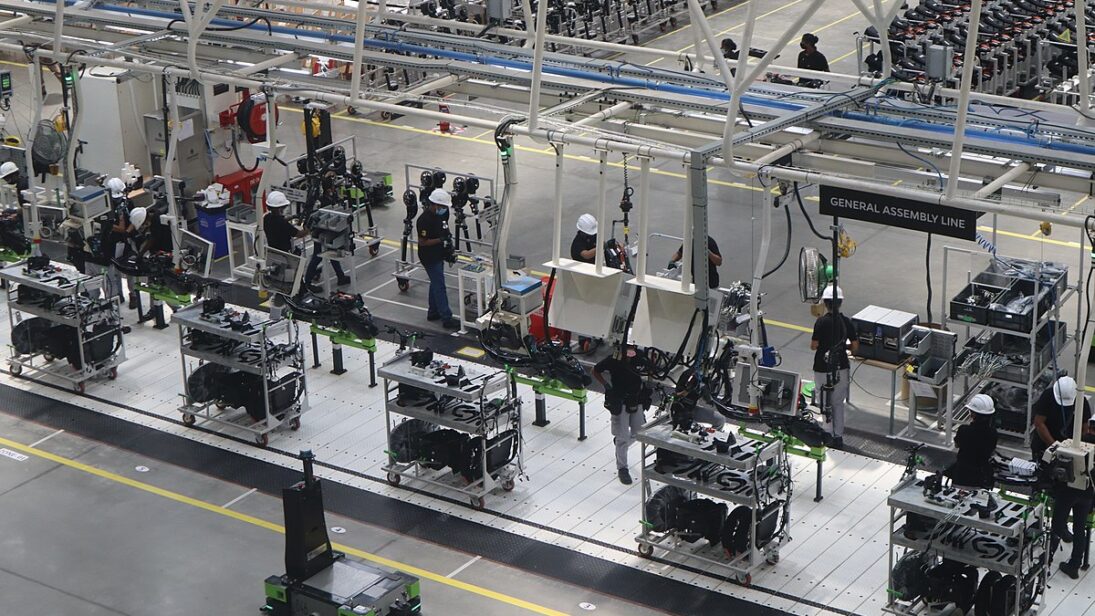

In addition to these factors, there are two further concerns that make it necessary for India to grow its manufacturing sector: a fraught geopolitical environment and the urgent imperative to decarbonize. These overlapping factors make a robust domestic manufacturing sector critical for India in its quest to become a developed economy and great power.

Strategic Importance of Manufacturing

A nation’s manufacturing sector is a key determinant of its military power. All emerging powers need to have a robust manufacturing sector because factories that churn out consumer goods can also be converted to produce weapons. Therefore, given the possibility of military confrontation with China and Pakistan and the need to avoid over dependence on external partners in wartime, India cannot afford to neglect its manufacturing sector.

Manufacturing is also critical to the overall strategic standing and leverage enjoyed by a nation. With the increased weaponization of economic networks through sanctions, export bans, and other measures, countries can no longer be content with merely improving the military prowess of their standing army. They must also improve their overall industrial capacity, including their infrastructure, energy supply, natural resources, and financial systems. The recognition of this link between domestic manufacturing capabilities and national security interests is what is, for instance, driving the West’s strategic goal of decoupling from China. The West understands that the production of essential goods cannot be located in the territory of a strategic rival. India too must realize the same and build its domestic industrial capacity.

This is not to say that India should decouple completely from geopolitical competitors such as China. Instead, it should engage with them to build its own capabilities. India recently eased visa restrictions on skilled Chinese technicians to help manufacturing units that are in the process of installing Chinese equipment. This is a welcome move toward leveraging China’s technical know-how for India’s own development. India needs to similarly encourage the influx of Chinese investment through joint ventures while ensuring that such investment helps boost India’s domestic capabilities. As commentator Mihir Sharma wrote, “To depend less on China in the long run, countries must engage with it in the medium term.”

Opportunity and Demands of Decarbonization

In the effort to build its manufacturing sector, India’s decarbonization goals can be an opportunity. India has set itself the ambitious target of achieving carbon neutrality by 2070. This will require the manufacture of new, carbon-efficient machines to replace the stock of existing machines. On the whole, this process will also create more jobs because clean energy measures tend to be more labor-intensive. One study found that for each USD $1 million shifted from fossil fuels to renewable energy, there will be a net increase of five jobs. India needs a Green New Deal of its own to take advantage of this energy transition — to create jobs, spur innovation, and create an export market for Indian firms in the clean energy sector, including in the manufacturing of electric vehicles, photovoltaic cells, and batteries.

A transition to clean energy without investing in domestic industrial capacity would render India vulnerable to external factors. In the face of geopolitical tensions, there has been an increase in export restrictions on critical minerals in recent years. Therefore, the endeavor for countries like India should be to advance the exploration and production of clean energy minerals. India has already identified 30 minerals that are crucial to its decarbonization efforts. India must not rely excessively on other countries for its supply of these minerals as it does for oil.

Manufacturing Investment is the Need of the Hour

While India certainly needs more of both manufacturing and service sector jobs, scaling up manufacturing remains the best bet for India’s relatively low-skilled youth. In the face of geopolitical tensions, manufacturing has become crucial for national security and industrial self-sufficiency. The need to decarbonize the economy also serves as an opportune moment for India to boost manufacturing.

…there are two further concerns that make it necessary for India to grow its manufacturing sector: a fraught geopolitical environment and the urgent imperative to decarbonize.

But in order to build its manufacturing sector, the Indian government will need to play a significant role in ensuring that resources reach the right projects. In this context, policies such as the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme — which provides financial incentives to manufacturing firms based on incremental sales — are welcome. In the same spirit, the government must stop providing state support in terms of grants, subsidies, and tax incentives to firms that fail to be profitable. As economist Dani Rodrik argues, “Successful industrial policy is not about picking winners, it’s about letting the losers go.”

The central government would also have to build collaborative institutions to ensure policy coordination across ministries, and between ministries and the private sector. Successful industrial strategies require the participation of multiple ministries, which often operate within silos. India must overcome this challenge by creating a body that facilitates cross-ministerial coordination. Such institutions should also involve technical, academic, and industry experts to help design policies, implement them, and track their outcome. This will enhance transparency in decision making and establish greater institutional credibility.

Finally, prioritizing public investment in healthcare, education, and vocational training is critical. According to the government’s latest Economic Survey, India’s public spending on education as a percentage of total expenditure has decreased from around 11 percent in 2017-18 to 9 percent in 2023-24. Spending on healthcare has only increased marginally from 5 percent to 6 percent in the same period. Investing in its youth, especially in the next decade or so, is key to India’s developmental goals.

As a country that has historically cherished its strategic autonomy, India cannot eschew the development of the manufacturing sector or of critical supply chains for clean energy minerals and other strategically vital resources. At a time when great power politics is reshaping the global order, India must reinvigorate its industrial capacity to ensure that it can stand as an independent power and command the direction of its own path.

Also Read: India-Afghanistan Critical Mineral Cooperation: Opportunities and Challenges.

***

Image 1: An electric scooter manufacturing plant via Wikimedia Commons.

Image 2: A manufacturing plant in Haryana, India via Flickr.

.