Contrary to the concerns of some international observers, India has been dealing reasonably well with the COVID-19 catastrophe, so far. From mid-January until March 8, India had recorded under fifty cases of infection compared to Iran’s 7,200, Italy’s 9,200, and China’s 80,900. India’s early risk assessment and stringent travel restrictions helped South Asia’s largest, most populous, and highly-connected country maintain a relatively low rate of confirmed positive cases at 0.4 per one million. However, the number of cases has been rising very rapidly in recent days, with the total as of March 24 at 536 with 10 deaths. As India imposes a national lockdown, possibly the largest in human history, effective March 25, all eyes will be on whether this unprecedented measure can help the country combat the menacing pandemic and arrest the global spread of COVID-19.

Contrary to the concerns of some international observers, India has been dealing reasonably well with the COVID-19 catastrophe, so far. […] As India imposes a national lockdown, possibly the largest in human history, effective March 25, all eyes will be on whether this unprecedented measure can help the country combat the menacing pandemic and arrest the global spread of COVID-19.

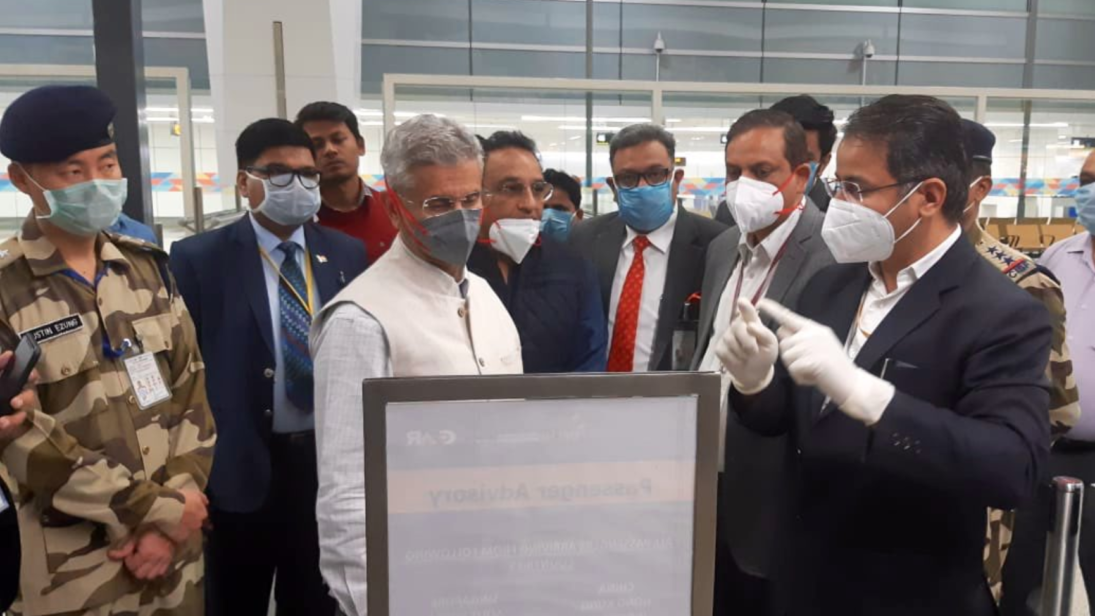

Indian authorities began assessing the potential risks of COVID-19 as early as January 8—three days after the news about a “pneumonia of an unknown cause” infecting people in Wuhan broke. Soon after, the government issued an advisory on suspending travel to China and began screening incoming passengers and testing individuals with travel history to the country, which allowed the early identification of cases. Over February, India reported only three positive cases—all with recent travel to China. However, as COVID-19 started taking the shape of a pandemic, spreading rapidly into Europe, South-East Asia, and the Middle East in March, India saw a sudden spate of cases. Leaders cautioned against large gatherings, and thermal screening began at airports, trains, tourist sites, hotels, and restaurants. After the country’s third coronavirus-related death, authorities ordered a shutdown of public places including schools, gyms, museums and theatres. Simultaneously, New Delhi continued carrying out several large-scale evacuations of its citizens from China, Italy, and Iran. As the epicenter of COVID-19 moved to Europe, India suspended visas for nationals of Germany, Spain, and France—a suspension it later extended to all foreigners. It also extended the quarantine requirement for all incoming travelers (including Indian citizens). These proactive measures were instrumental in avoiding a higher fatality rate.

However, as the cases began to rise despite early action, India banned all international traffic into the country and Prime Minister Narendra Modi created momentum for an eventual lockdown by appealing for a self-imposed public curfew (called “Janata Curfew”) on March 22. Subsequently, all passenger train and domestic air services were also suspended, all border checkpoints closed, and public transport restricted. On March 24, Modi finally announced a complete national lockdown for three weeks starting March 25 and promised an emergency healthcare package of around USD 2 billion to fight the virus. This prudent step was taken relatively early in India’s COVID response cycle at 10 deaths, whereas Italy and Spain saw 800 and 200 deaths respectively before they imposed their lockdowns.

The government’s COVID-19 response faces a few critical challenges. Some experts fear that India’s low rate of testing may be masking the actual number of COVID-19 cases in the country. Secondly, there are concerns about the costs of the national lockdown, particularly on the Indian economy and those employed as casual labor and within the country’s large unorganized sector.

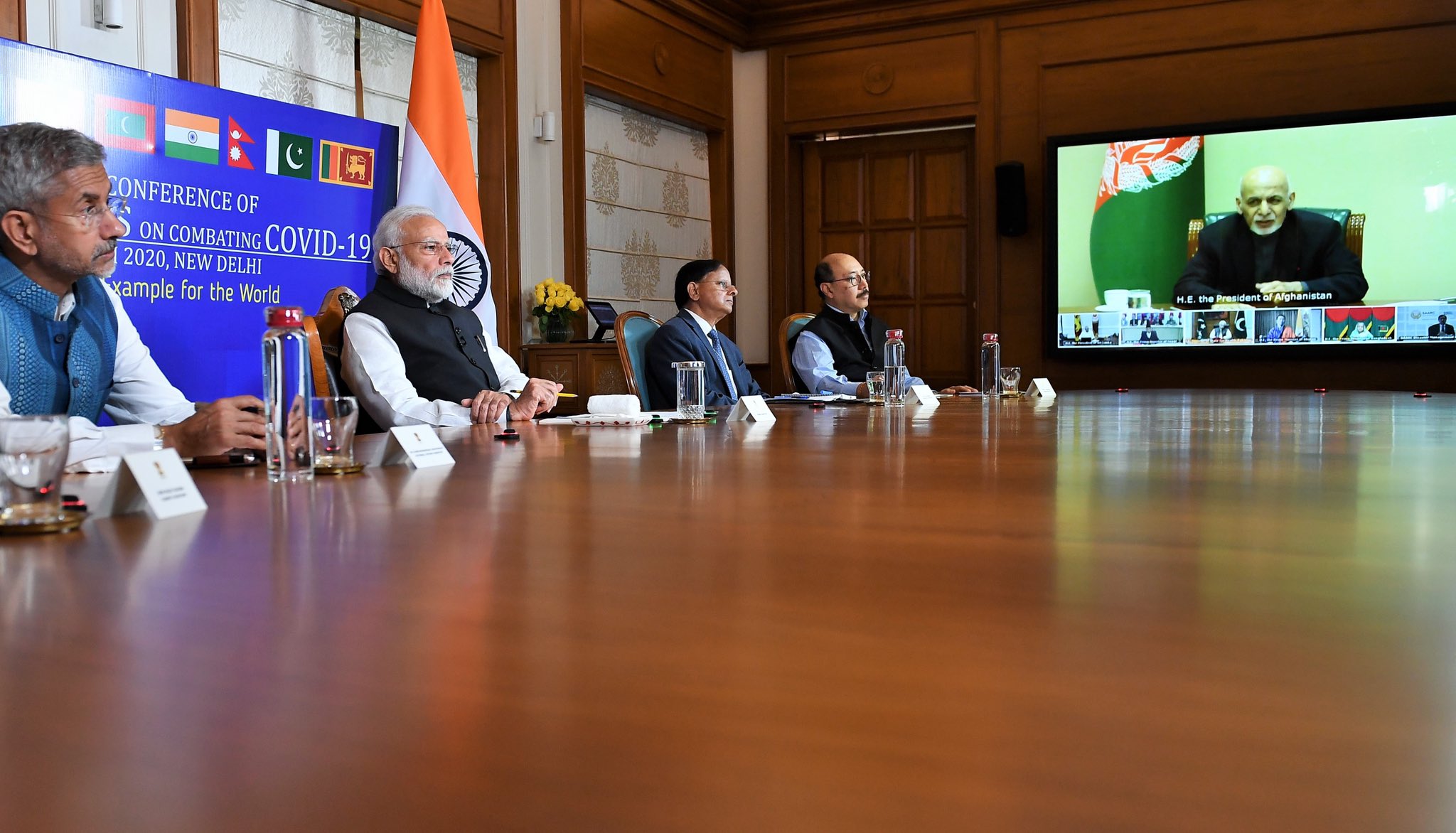

Relatively advanced medical facilities have allowed India to recover the most number of COVID-19 patients in South Asia. In fact, India has been leading efforts to formulate a regional response to the outbreak and has been offering medical assistance as well as evacuating citizens of neighboring countries from affected regions. To minimize the community spread of the infection, it has been stamping individuals ordered to mandatorily home-quarantine, and tracking violators. The combination of affordable mobile data and dedicated coronavirus web-chats and mobile applications has not only enhanced community awareness about the disease but also enabled community policing of misbehavior.

However, the government’s COVID-19 response faces a few critical challenges. Some experts fear that India’s low rate of testing may be masking the actual number of COVID-19 cases in the country. Secondly, there are concerns about the costs of the national lockdown, particularly on the Indian economy and those employed as casual labor and within the country’s large unorganized sector. Finally, a deluge of misinformation online propagating incorrect cures for the disease could impact India’s fight against COVID-19.

India has announced several steps to address these issues. It plans to import more test kits even as an indigenously-made test kit has been granted commercial approval. The government has also allowed some private labs to conduct testing. Further, an economic task force has been set up that is expected to announce relief packages for the worst-hit sectors of the economy very soon. Finally, cyber chatbots will be utilized to quell the spread of online misinformation.

As countries debate the efficacy and practicality of preventive lockdowns, the Indian government’s attempts to implement it in a country of 1.3 billion people are sure to be instructive. If this measure succeeds in flattening India’s upward climb along the coronavirus curve, it would be no mean feat.

Editor’s Note: SAV contributors analyze how governments in the region are responding to the spread of COVID-19, as well as the potential far-reaching economic and security impacts of the pandemic. Read the entire series here.

This piece also appears as part of the Stimson Center series Coronavirus Response in Asia, featuring expert voices on how governments throughout Asia are responding to the pandemic. The article can be viewed on the Stimson Center website here.

***

Image 1: S Jaishankar via Twitter

Image 2: Narendra Modi via Twitter