India witnessed a massive rise in COVID-19 cases due to the advent of the Delta-variant in April 2021, with the country recording 1,876,792 cases in a day at the height of the pandemic. The public healthcare infrastructure collapsed because of rising infection rate while the private healthcare system came under considerable strain. The “tsunami of cases” that India witnessed exposed pre-existing vulnerabilities within India’s healthcare system as shortage of basic medical equipment—such as oxygen cylinders and ventilators—led to a massive death toll. The Indian healthcare system as fewer oxygen cylinders meant that fewer lives could be saved, as India’s daily oxygen requirement increased by 76 percent in just 10 days—from 3,842 metric tons (MT) on April 12, 2021 to 6,785 MT on April 22, 202. During this time, India produced only 7,127 MT.

A year on, as India recovers from the pandemic, public health appears an issue of peripheral importance for the Indian state. As India focuses on conventional security threats, prioritizing a realpolitik foreign policy, it has failed to rebuild trust in government institutions, invest in state infrastructure, and address poor governance domestically. Social security issues like public health have so far received scant attention in India. However, if India is to reverse the tide and build towards its great power ambitions, India must transform itself on the global stage and become a “net healthcare provider.” This would involve providing healthcare benefits to its core and peripheral neighborhood in the form of vaccines and other medical care and engaging proactively with international organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO). India can only assume this role after improving its performance in the healthcare sector domestically by investing in good governance and institutional infrastructure.

Healthcare in India

The central government’s lack of commitment to public health stems from the fact that public health is categorized as a subject within the “state list” in the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution, meaning states/provinces can legislate on the issue without interference from the central government. India attempts to follow a healthcare model that sees a convergence between the ideal Bismarckian (welfare) and Beveridgean (taxation) model. According to this model, taxation and state intervention act as catalysts in ensuring the well-being of the citizenry, and public and private players collaborate to provide healthcare to the citizens. Yet the “right to health” is not explicitly mentioned as a fundamental right in the Indian constitution and it is read into the constitution through judicial interpretation, weakening the healthcare distribution apparatus in India.

India can only become a net provider to its neighborhood after improving its performance in the healthcare sector domestically by investing in good governance and institutional infrastructure.

India allocates less than two percent of India’s GDP to healthcare. In comparison, Japan, at 9.2 percent, and China, at 2.9 percent, invest more in healthcare. As a result of this low government allocation, most Indians pay out-of-pocket for access to healthcare facilities and 70 percent of India’s population opts for private healthcare. These figures are staggering considering nearly one-third of India’s population lives below the poverty line and the pandemic has pushed over 230 million more Indians into poverty.

COVID 19 & India’s Response

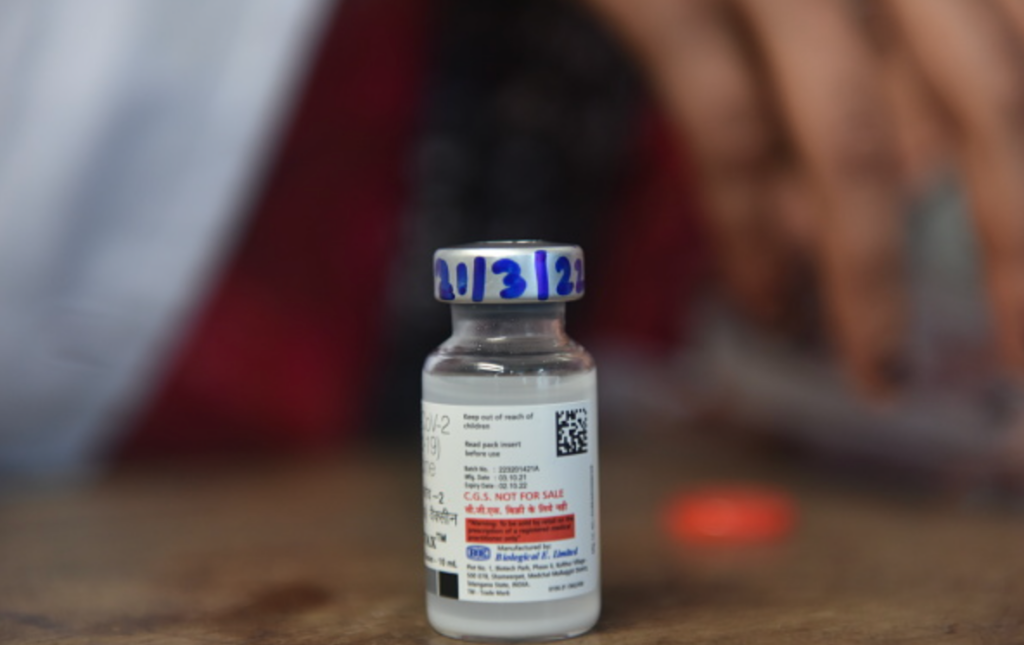

India’s failed response to pandemic has negatively affected its image at the international and national stages. Internationally, India’s inability to reinitiate the Vaccine Maitri initiative in its neighborhood—despite being the largest producer of vaccines globally—has demonstrated its limited capacity for managing global health crises, giving China an opportunity to expand its footprint in South Asia. Initial goodwill generated by the Vaccine Maitri initiative has not endured a year on as India’s failure to provide vaccines to its neighbors led them to opt for alternative sources to meet their needs. As a result, India’s soft power credentials have taken a hit as India’s inability to provide vaccines has exposed its limitations as a core supplier of medical equipment.

India’s inefficient management of the pandemic has, in setting back its domestic development and international perceptions, dented India’s great power ambitions. The India’s Vaccine Maitri initiative was careless and mismanaged given India’s own population had not yet been vaccinated. This act of self-sabotage — providing vaccines to its neighborhood and beyond at the cost of its own population—ultimately can be attributed to poor governance on the part of the Indian government. On the international stage, this negatively affected India’s ability to play crisis manager on the international stage, exposing a crucial mismatch between India’s intentions and capabilities. Beyond affecting India’s image on the international stage, this volte-face exposed the inherent inefficiencies present in India’s ineffective healthcare system.

At the national level, the pandemic also sharpened class and caste inequalities within India. The state acted as a racketeer during the pandemic and monopolized violence while targeting poor migrants—citizens who could not adhere to social distancing norms due to their existing limitations that were exacerbated during the pandemic. The Guardian aptly captured this brutal treatment meted out to migrant workers by law enforcement agencies as it wrote “the crush of human bodies was the antithesis of the social distancing ordered by Modi, and the police responded by beating up workers who tried to board the buses.” These instances effectively eroded the citizens’ trust in government institutions.

Among wealthier city-dwellers, erosion of trust meant a preference for private healthcare—an option that is not accessible to the poor. The Indian state effectively rendered its poorer citizens invisible—in many instances, deaths of citizens without access to resources were not included among official counts.

Prioritizing Healthcare

If the present election results are taken as a gauge, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has escaped with seemingly greater popular support than ever despite pandemic mismanagement. Still, the COVID-19 crisis has now given ammunition to Modi’s political opponents—regional parties like the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) and All-India Trinamool Congress (AITC) —that have focused on healthcare and education in their respective regional states and managed the pandemic’s impact.

To sustain influence over the Indian populace and nullify the pandemic’s continued impact, Modi should focus on healthcare in addressing governance challenges. The government must emphasize implementation of flagship initiatives like “Ayushmann Bharat” that provide free healthcare to India’s marginalized populations. It should also work to pass the 2017 Public Health Bill meant to replace the out-of-date 1897 Epidemic Diseases Act, 1897—India’s primary legislation on healthcare and a relic of colonial rule.

The government must emphasize implementation of flagship initiatives like “Ayushmann Bharat” that provide free healthcare to India’s marginalized populations.

Internationally, India should focus on creating indigenous vaccines and Indian Research & Development (R&D) like the E-Vidya (Knowledge) Bharati and Arogya (Telemedicine) initiative between India and African countries like Seychelles and Sierra Leone. Through this initiative, India provides educational scholarships for studying medicine to students across these programs after fulfilling India’s local needs. Finally, India should engage with international organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) and incorporate the perspectives of the Global South before it can become a rule maker within the global health order.

***

Image 1: Noah Seelam/AFP via Getty Images

Image 2: NurPhoto via Getty Images