On December 9, the UN General Assembly overwhelmingly endorsed a United States resolution that sought to prohibit direct-ascent anti-satellite tests (DA-ASATs), following a moratorium endorsed by the UN First Committee on Disarmament and International Security in early November. The moratorium calls for a ban on anti-satellite weapons (ASATs) in the form of medium or long-range missiles launched from Earth, which can destroy satellites in space. The stated motivation for the resolution is twofold—to prevent an aggressive arms race in outer space and to avoid the creation of debris in Earth’s orbits. While not legally binding, 155 states voted in favor of the resolution and nine countries voted against, including China and Russia, who strongly lobbied against the resolution. There were just nine abstentions, one of which was India.

As a primary actor in outer space, India’s abstention from the ASAT missile test moratorium is not as simple as a neutral vote. It is indicative of India’s national strategy in space – an unsaid policy of strategic ambiguity.

India is one of only four countries – besides the United States, Russia, and China – to have ever conducted DA-ASAT missile tests in the past. By only partially aligning with the U.S.-Artemis bloc, India retains enough legroom to address its own national security concerns and maintain its strategic autonomy in outer space affairs.

India’s Legislative and Organizational Environment in Outer Space

While India’s space program is governed by a host of national laws and international agreements, it does not have an official national space policy defining its civil and military goals in outer space. In its diplomatic messaging, India has long maintained the position that it seeks to use space technology to benefit Earth and that outer space should be used for peaceful purposes. Notably, unlike the United States, China, and Russia, the Indian space program is founded on a civil rather than a military organization – the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) – which continues to be the center of India’s space activities.

However, two significant developments have changed the Indian space landscape in recent times. First, India opened its space industry to private players such as Skyroot and Pixxel in 2020. Second, India has begun to recognize the military importance of outer space, successfully conducting its first direct-ascent ASAT test in 2019. That year, it also established the Indian Defense Space Agency (DSA), an organizational equivalent to the U.S. Space Force, and the Defense Space Research Organization (DSRO), which supports the DSA and develops civilian space technologies for military use.

India’s historic position of strategic autonomy in its foreign policy is also reflected in its space diplomacy on the international stage. India is one of the few countries with a robust space program that has not signed the U.S. Artemis Accords, which are multilateral agreements between the United States and other countries to establish frameworks for civil exploration and use of the Moon, Mars, and beyond. However, India does cooperate on a range of civil and military space activities with the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) and through different bilateral instruments, including with the United States, allowing it to maintain its national security priorities in space. Thus India maintains ‘partial alignment’ with the bloc, whereby it cooperates on selective activities.

Addressing India’s National Security Concerns

ASAT capabilities and space security have become increasingly important to India due to its asymmetric capabilities compared to China, both in space and on Earth. Indian strategic focus on space security has paralleled increased Chinese investment in technology, such as in ‘informationized war’ capabilities. Meanwhile, the United States’ continued modernization and expansion of its own space capabilities is fueling the Chinese pursuit of the same. The result is a security ‘trilemma’, roping India into the great power competition taking place in outer space.

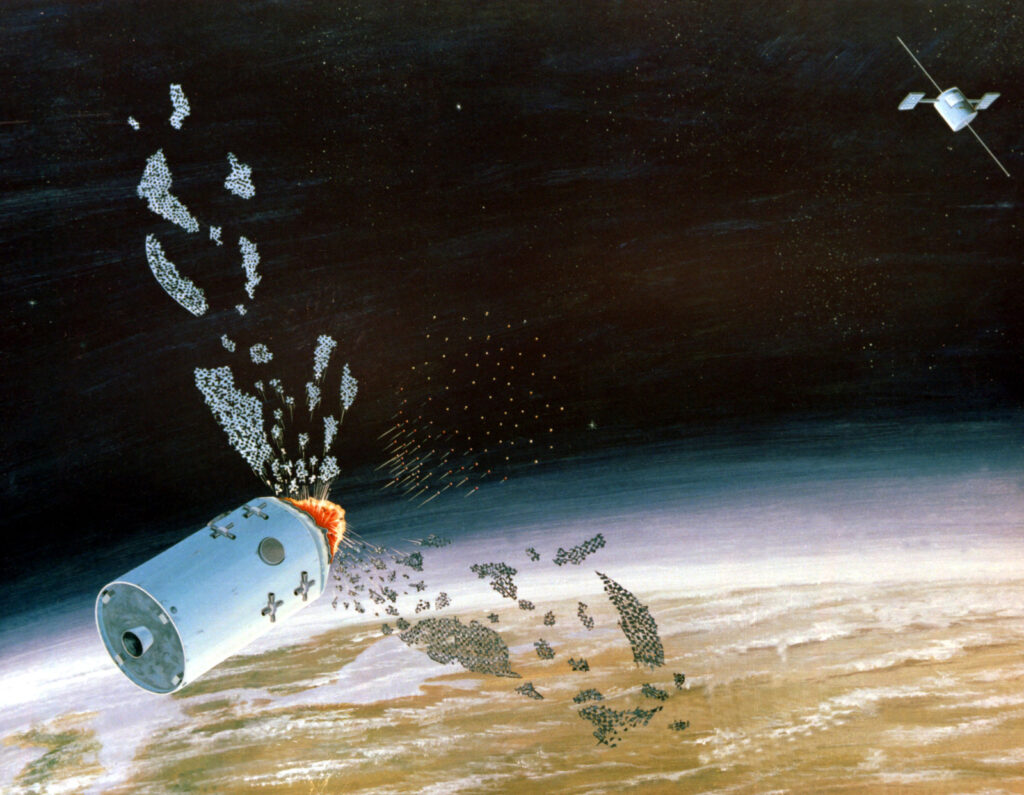

India developed its anti-satellite technologies on the defensive in an apparent response to threat perceptions after the Chinese ASAT test in 2007. India successfully demonstrated its DA-ASAT capabilities on March 27, 2019, using a ballistic missile defense interceptor to hit a micro-satellite placed in orbit as a target. Prime Minister Modi reiterated that the test did not violate any international agreements and that India was working to ensure space security and protect its satellites. Exemplified by its name, ‘Mission Shakti’(‘power’), the test was likely meant to deter aggression from adversaries like China and to signal that an attack on Indian satellites could result in a quid pro quo response.

For the DA-ASAT to be a persuasive deterrent, India’s commitment to its use must be credible –or at least be perceived as credible. By abstaining from voting for the resolution banning DA-ASAT tests, India maintains strategic and political ambiguity on the subject, allowing it to use such tests as a tool in its deterrence arsenal to pursue its national security goals. India is not alone in recognizing the deterrence capability of ASAT weapons. When Vice President Kamala Harris first announced the United States’ pledge against DA-ASAT tests, the move received criticism from congressional Republicans, who expressed concerns that the move did nothing to deter adversaries and could have the opposite effect.

Policy Recommendations

Given the value that outer space brings to Earth – from GPS, satellite imagery, and communication to the likely exploration and mining of the moon and other celestial bodies – outer space is and will continue to be a vital military domain. International efforts to demilitarize outer space have been in a deadlock between the U.S.-Artemis and the Russia-China blocs for years. Since the civil and military space budgets and capabilities of space powers like the United States and China dwarf that of India, a rule-based international order is firmly in India’s interest. Addressing the root of space threat perceptions by building international instruments can reduce the possibility of space warfare. This might aid India in maintaining its position of using space technology to benefit Earth and preserving the domain for peaceful purposes.

While the moratorium might prima facie appear to be a step in that direction, it does little to stop the slippery slope of space weaponization, because it specifically bans one method of testing for a single type of ASAT weapon. DA-ASAT weapons can still be tested in orbit through intentional fly-bys, and there are numerous other methods, both kinetic and non-kinetic, to eliminate or disable enemy satellites. However, while the ban does not constrain the development and fielding of offensive space capabilities, the moratorium on DA-ASAT weapons does help prevent the generation of dangerous space debris. Abstaining from the moratorium is still compatible with adhering to the principle of not conducting DA-ASAT tests that generate dangerous space debris—this is a norm India should participate in building. The destruction of a satellite inevitably generates a significant amount of debris, which impacts not only foreign satellites but also the actor’s own space objects.

India’s approach of using strategic ambiguity should not be confused with reticence. Instead of letting its abstention slip into the shadows, it should seize the moment to debate the efficacy of the ASAT moratorium.

India has some visibility and negotiating power, given that it is one of four countries to have tested an ASAT weapon. India’s strategic ambiguity might allow it to leverage its position to bring outer space powers to the negotiating table to promote transparency and confidence-building measures as a first step instead of direct arms control. This could include focusing on non-military issues such as technology transfers and space traffic management, dual issues like space debris generation by ASAT tests and commercial mega-satellites, and registering military and non-military satellites and attributability of actions in space. India should commit to creating international space laws to prevent unilateral norm-building and also irresponsible behavior in outer space.

***

Image 1: Night View of India-Pakistan Borderlands via Flickr

Image 2: Artist Concept of ASAT Weapon via NARA