In March 2021, the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) passed Resolution 46/1, which mandated a new process to collect, analyze, and preserve evidence of crimes committed during Sri Lanka’s 26-year-long civil war. Originating in ethnic tensions between the minority Tamil and majority Sinhalese communities, the civil war fought between the Sri Lankan government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) has left the island with a legacy of war crimes that have yet to be addressed. There have been seven resolutions on the Sri Lankan civil war at the UNHRC in the past twelve years, none of which have been implemented in full. While other countries reeling from conflict have set up war crimes tribunals, truth commissions, reparations schemes, and many other transitional justice mechanisms, Sri Lanka has not. This raises the question: Why have efforts to pursue transitional justice been so unsuccessful in the Sri Lankan context?

There is little incentive to prosecute those who committed war crimes on the victors’ side, many of whom continued to serve in government and the military after the war’s end. The Sri Lankan political elite’s embrace of Sinhala Buddhist nationalism has also contributed to popular narratives questioning Western approaches to human rights, producing a framework that the government uses to push back against transitional justice measures. President Gotabaya Rajapaksa and former President Mahinda Rajapaksa have both used nationalist rhetoric to justify Sri Lanka’s pivot away from the West and towards China—which they portray as a successful challenger to Western imperialism—while the previous administration under Maithripala Sirisena pursued half-hearted transitional justice measures to reinstate amicable ties with the West while limiting its antagonization of the Sinhala Buddhist electorate. Consequently, all of Sri Lanka’s political administrations since 2009 have leveraged their international partners to evade implementing transitional justice measures. Though Sinhala Buddhist nationalism has often been viewed through the prism of domestic politics, the majoritarian ideology’s rejection of modern, global, and Western phenomena has informed Sri Lanka’s foreign policy and geopolitical alignments concerning post-war transitional justice.

Historicizing Sinhala Buddhist Nationalism

Emerging as a philosophy that sought to champion Sinhala Buddhist dominance in direct response to colonial denigration, Sinhala Buddhist nationalism has influenced Sri Lanka’s responses to Western-led human rights initiatives. Sinhala Buddhist nationalists vilified international efforts to provide humanitarian relief during the civil war, highlighting their supposed “anti-Sinhala bias” and regarding them as “proponents of an American funding evil Western conspiracy.” Nationalist opposition to international involvement in Sri Lanka continued after the war’s end: Sinhalese Buddhist monks protested visits from UN officials to investigate concerns over alleged war crimes, accusing a responding police blockade of “taking the side of anti-Sri Lankan forces in the West.”

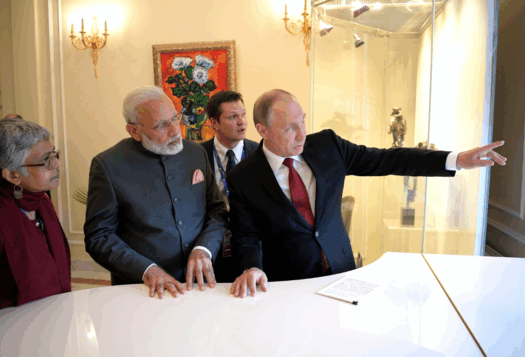

After becoming president in 2005, Mahinda Rajapaksa harnessed this nationalist movement against foreign intervention throughout the Sri Lankan civil war, consequentially shaping Sri Lanka’s geopolitical alliances. Positioning his legitimacy on his struggle against imperialist Western states and Tamil terrorism to attract his Sinhala Buddhist base, Rajapaksa campaigned against “foreign countries unnecessarily intervening into our internal affairs” in the name of peace. As Mahinda Rajapaksa’s administration garnered criticism from the West, led by the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada, over its human rights record and final military campaign against the LTTE during the war, Sri Lanka’s alliances shifted towards countries like Iran, China, and Russia. During the war itself, China and Pakistan were the primary suppliers of arms for the Sri Lankan government, which enabled government forces to conduct a bloody final offensive and ultimately win the war.

Though Sinhala Buddhist nationalism has often been viewed through the prism of domestic politics, the majoritarian ideology’s rejection of modern, global, and Western phenomena has informed Sri Lanka’s foreign policy and geopolitical alignments concerning post-war transitional justice.

Sri Lanka continued pursuing closer relations with China after the war’s end, when Rajapaksa’s government received USD $1.5 billion in loans from China and economic assistance to build a port in his hometown of Hambantota. China also shielded Rajapaksa from attempts to conduct investigations into human rights violations and war crimes, consistently backing Sri Lanka in the UN Human Rights Council and threatening to veto any formal Security Council involvement. The Rajapaksa’s alliances fomented during the war carried over into the war’s aftermath, shaping international engagement and domestic pressures to the transitional justice process in Sri Lanka.

Transitional Justice Geopolitics

The Sirisena Administration

Although Sri Lanka attempted to distance itself from China and engage in closer foreign relations with the United States and other Western countries after Maithripala Sirisena’s election in 2015, post-war transitional justice efforts still faced Sinhala Buddhist antipathy at home. Sirisena had run on a platform that criticized Mahinda Rajapaksa’s close relationship with China and sponsored Resolution 30/1 to address the UN and Western nations’ concerns on Sri Lanka’s geopolitical allegiances and human rights record. While initially hailed as a crucial step towards transitional justice, Resolution 30/1 failed to be fully implemented after President Sirisena asserted that foreign judges should not investigate “internal” issues like war crimes. Then-opposition leader Mahinda Rajapaksa also claimed that President Sirisena had betrayed the country for a “Western agenda.” The Sirisena government used transitional justice as a pretext to advance its foreign policy goals but succumbed to domestic pressures, ultimately costing genuine post-war accountability and reconciliation measures.

With the Sirisena administration leaning towards the West, the United States and other Western countries eased off their pressure on the Sri Lankan government to adopt transitional justice measures to avoid restrengthening the Colombo-Beijing axis. Upon the Sri Lankan government’s sponsorship of Resolution 30/1, human rights organizations and government officials from the United States and other Western countries were quick to praise Sri Lanka’s restoration of democracy and return as a “global champion of human rights and democratic accountability.” These countries also helped postpone the publication of a UN inquiry into the Sri Lankan government’s war crimes and secured successive two-year extensions for UN Resolution 30/1’s implementation. Even as the Sirisena administration continued some of the same majoritarian policies as its predecessors—including the increased militarization of Tamil-majority areas and barely addressing anti-Muslim violence after the 2019 Easter Sunday attacks—Western allies remained conciliatory.

The Second Rajapaksa Administration

Like his brother before him, Gotabaya Rajapaksa has used Sinhala Buddhist nationalist rhetoric to question Western demands for post-war accountability, consequently prioritizing Sri Lanka’s relationship with China to gain international support against enacting transitional justice measures. As Minister of Defense during the civil war accused of war crimes himself, Gotabaya Rajapaksa campaigned to repeal the previous government’s transitional justice commitments and exit international bodies that threatened to prosecute soldiers involved in war crimes with overwhelming support from his majority Sinhala-Buddhist supporter base. After the Sri Lankan government announced that it would be withdrawing from all UN resolutions concerning its transitional justice process in February 2020, Chinese top diplomat, Yang Jiechi, assured President Gotabaya Rajapaksa that China would defend Sri Lanka’s independence, sovereignty, and territorial integrity “at international fora including the United Nations Human Rights Council.”

In aligning with China—a rising power whose global appeal partially derives from challenging the presupposed dominance and legitimacy of the West—the Sri Lankan government gains an ally that provides crucial backing for Sri Lanka’s future aspirations without seeking to apply double standards of international norms. While some influential Buddhist clergy members have expressed reservations on Sri Lanka’s “colonial” status in its relationship with China, it is still unlikely that Sri Lanka will lose China’s support on transitional justice matters if the governments of Sri Lanka and China continue to work together quietly on the economic and geopolitical front. China’s dependability as a source of economic and political support in the face of criticism from other countries about Sri Lanka’s human rights record enables the Sri Lankan government to evade the international pressure to implement comprehensive transitional justice mechanisms, and the Sri Lankan government will continue to use Sinhala Buddhist nationalist rhetoric as an excuse to justify their pivot towards China.

The Future of Transitional Justice in Sri Lanka

In response to Resolution 46/1’s passage, Foreign Minister G. L. Peiris said Sri Lanka rejects “any external initiatives” established by the UN, continuing the pattern of using Sinhala Buddhist nationalist rhetoric cautioning against external interventions to evade transitional justice commitments. While the Sri Lankan government has honored some commitments in name, such as establishing an Office of Missing Persons and an Office of Reparations, they have failed to implement these fully and enact other key reforms. In delaying promised transitional justice measures, the Sri Lankan government has expanded its majoritarian policies to continue pandering to the Sinhala Buddhist majority: pardoning soldiers accused of war crimes and banning burqas and Islamic schools for “national security” purposes.

As Sinhala Buddhist nationalism becomes further institutionalized in Sri Lanka’s foreign policy rhetoric and engenders its pivot towards China for economic gain and political cover, Sri Lanka’s ability to implement meaningful transitional justice measures remains limited.

Though the decision to pursue transitional justice remains in the hands of the Sri Lankan government, additional motivation from the international community has waned as the United States and China compete for more influence. Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s administration has continued to “prioritize” relations with China, vowing to “never bend to pressure from major powers outside the region.” Although the UN raised concerns over democratic backsliding in Sri Lanka and started working on Resolution 46/1’s implementation in September, the United States has remained relatively silent. Moreover, the United States has found its efforts to engage with Sri Lanka rebuffed due to perceptions that their support is conditioned on reducing Sri Lanka’s ties to China. As Sinhala Buddhist nationalism becomes further institutionalized in Sri Lanka’s foreign policy rhetoric and engenders its pivot towards China for economic gain and political cover, Sri Lanka’s ability to implement meaningful transitional justice measures remains limited.

***

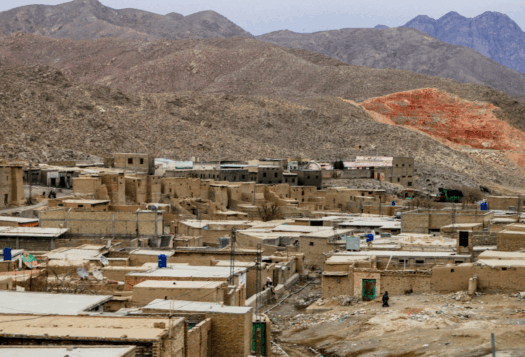

Image 1: Vikalpa, Maatram, and Groundviews (CPA) via Flickr

Image 2: Mahinda Rajapaksa via Flickr