China’s increasing forays in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) through its naval assets, have added a brand new dimension to the security dynamic of the region. China’s decades-long economic prosperity has led to expansion of its military and economic influence across South Asia. In recent years, arms supplies and debt funding have proven to be the backbone of Chinese policy in South Asia, especially with regards to the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka.

The role of China in Sri Lanka, which has grown remarkably in recent years, is poised to expand geographically further. It all began with Chinese capital and infrastructure funding in building the controversial port in Hambantota, which is additionally often referred as one of the pilot projects by Beijing for the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

China’s increased strategic interest and presence on the island of Sri Lanka, close to Indian waters, has been attributed to the legacy of Mahinda Rajapaksa’s presidency, when China was one of the few countries to come forward to support Sri Lanka in its final fight against the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in 2008-2009. While other actors such as the United States and European Union were critical of the Sri Lankan Army’s conduct during the final stages of the Sri Lankan Civil War, Beijing provided millions of dollars worth of sophisticated weapons, as well as six F-7 fighter jets to the Sri Lankan Air Force. Moreover, Beijing effectively shielded Sri Lanka from U.S. resolutions at the United Nations Security Council which accused Sri Lanka under Rajapaksa of human rights violations during the final offensive against the LTTE.

Sri Lanka and her major ports now form an integral part of the Belt and Road Initiative, and may just be the herald of a wider program of Chinese economic and military projects in the years ahead. A large Chinese footprint may become the new normal in South Asia and the Indian Ocean.

Since then China’s presence in Sri Lanka has only grown and is no secret to anyone, let alone to India the country’s closest neighbor and Beijing’s principal strategic rival for influence. Chinese ships and workers can be openly seen working on major projects such as the Port City project near Colombo. As Ken Miller argues in a recent piece, Beijing’s economic power in South Asia via overseas investments has been a deliberate tactic used to help bolster its wider national security interests. China’s financial foreign policy depends on: “accumulating foreign currency reserves and sending money abroad in the form of FDI, aid, assistance and loans”.

China’s twin economic and security roles

Sri Lanka is a model for the latter part of this stratagem. Beijing is Sri Lanka’s biggest source of foreign direct investment as well as providing expansion loans for projects such as new Colombo Port Terminal, Hambantota Port, Sri Lanka’s first four-lane expressway, and a new National Theater, among others. From 2005 to 2017, China invested USD around $15 billion into projects in Sri Lanka.

The friendship between Sri Lanka and China, which has its origins centuries earlier through the ancient Maritime Silk Road, has often been viewed in the context of geopolitical competition with India and other actors in the Indian Ocean and wider Indo-Pacific. Connecting Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Asia, the Hambantota port and Colombo International Container Terminal now serve as strategic assets for China. As part of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing now owns an 85 percent stake in Colombo International Container Terminals–currently the only deep-water terminal at the port.

Sri Lanka is strategically located in the region given its proximity to important sea lanes of communication. In 2009, the United States Senate’s Foreign Relations Committee stated that “Sri Lanka’s strategic importance to the United States, China and India is viewed by some as a key piece in a larger geopolitical dynamic”. China’s active forays in the IOR—that began with Beijing’s assistance to Mahinda Rajapaksa administration in a fight against Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE)—through its naval power have added a new dimension to the security dynamics of the region.

In April 2018, China Railway Beijing Engineering Group won a contract of over $300,000 million USD to build 40,000 houses in Sri Lanka’s Jaffna district. Jaffna had suffered extensive damage during Sri Lanka’s civil war. Sri Lankan President Maithripala Sirisena’s recent visit to Beijing on 14 May 2019, saw Sri Lanka request more military equipment to aid in counter insurgency operations. China agreed to the request, providing aid worth USD $14 million for Chinese-made counterinsurgency equipment intended to boost the capability of Sri Lanka’s domestic security forces. China has also agreed to provide Sri Lanka’s police force with over 150 vehicles.

Given China’s economic inroads and growing security presence, Beijing looks set to turn Sri Lanka into a modern day “semi-colony,” the same way Great Britain and Portugal turned specific cities in southern China into their own semi-colonies back in the mid of 19th century.

Following the Easter Sunday terror attacks which killed over 250 people on April 21, Sri Lanka requested additional equipment from China. Beijing reportedly provided an estimated USD $4.2 million worth of equipment, including “500 hand held metal detectors, 25 walk through safety inspection gates, 50 X-ray security inspection systems, 25 hand held vehicle scanners, three explosive detectors and three explosives and narcotics trace detectors.” China also reportedly sent a technical team to Sri Lanka for installation and training.

China has gifted a warship frigate “P625” to Sri Lanka, in the latest sign of its deepening military cooperation with the strategically located island nation. The Chinese navy likewise hosted professional training for more than 110 members of the Sri Lankan navy and sailors in Shanghai.

The fast changing geopolitical situation in the IOR has kept India’s foreign policy establishment on its toes. In this region a large number of small islands states are developing greater importance. Given China’s economic inroads and growing security presence, Beijing looks set to turn Sri Lanka into a modern day ‘semi-colony,’ the same way Great Britain and Portugal turned specific cities in southern China into their own semi-colonies back in the mid of 19th century.

Two countries in India’s backyard, Sri Lanka and Maldives, have relatively greater geostrategic importance in the IOR compared to other neighbors, as a result they have long been on the Chinese strategic radar. Sri Lanka, owing to its proximity to India and population size, figures prominently in the minds of policy makers in New Dehli and is kept on the top of India’s radar due to China increasing interests on the island and the implications for the wider IOR. The strategic location of Sri Lanka is such that it has always attracted the attention of various great powers, previously the United Kingdom but more recently the United States. Sri Lanka despite being a smaller state in the IOR has developed significant relevance for China, who now too seems determined to act as the island’s main economic and security guarantor.

Risks versus rewards: rising debt and influence

China’s influence however comes at a cost for Sri Lanka, as has been recently witnessed. As previously stated, China’s increased footprint in Sri Lanka began back in 2007, when Beijing provided military and diplomatic support to end the nearly three decade conflict with the Tamil Tigers. Chinese financial assistance proved invaluable for the maintenance of the Sri Lankan economy, in particular, infrastructure developments such as the above mentioned, Port City, Hambantota Port and Colombo International Container Terminal. A decade later, however, Sri Lanka’s debt was standing at 77.6 percent of the country’s GDP, with its budget deficit at 5.5 percent of the country’s GDP.

As a result of this debt crisis Sri Lanka has been forced to turn to China for loans, China has in the last few years become the largest lender to Sri Lanka, with many of the original loans signed during Mahinda Rajapaksa’s government. In 2020, Sri Lanka owed USD $4.8 billion in loans, many attributed to Rajapaksa’s earlier presidency for loans that led to the construction of the Hambantota port, a new airport, a coal-fired power plant and multiple new highways. In 2017, when Sri Lanka could no longer afford the debt repayments Beijing simply took over Hambantota on a 99 year lease and wrote off a debt of $1.1 billion.

Beginning in 2007, Chinese financial assistance proved invaluable for the maintenance of the Sri Lankan economy, in particular, infrastructure developments such as the above mentioned, Port City, Hambantota Port and Colombo International Container Terminal. A decade later however Beijing’s chickens have come home to roost.

China seems to have learnt well from history of international politics and especially from the Marshall Plan of United States of America. However, the Marshall Plan primarily used grants whereas China lending is focused on loans and not grants to various countries where it has taken up infrastructure projects. The difference is that China expects a return for its money, whereas the United States was more interested to earn the loyalty of the countries at the expense of its money. The fact remains that these debts will continue to grow and Sri Lanka will remain on the hook for repayments in one form or another for a long time to come.

In conclusion, the IOR is of significant geopolitical importance to China and its growing influence in Sri Lanka reflects this. China’s objectives are to develop its influence further through major ports of the littoral states in the region, giving Beijing access to secure vital sea lines of communications for its maritime security.

Sri Lanka’s geopolitical location provides the best opportunity for China to achieve this strategy. Furthermore, with tensions rising between India and China over several geopolitical issues including the border, Sri Lanka offers China a strategic asset with which to diminish India’s influence in the Indian Ocean. Over the last decade China has successfully built a large footprint in the IOR which only looks set to increase amidst the rising financial aid to Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Maldives. Sri Lanka and its major ports now form an integral part of the Belt and Roads Initiative, and may just be the herald of a wider program of Chinese economic and military projects in the years ahead. A large Chinese footprint may become the new normal in South Asia and the Indian Ocean.

Editor’s Note: A version of this piece originally appeared on 9DashLine and has been republished with permission from the editors.

***

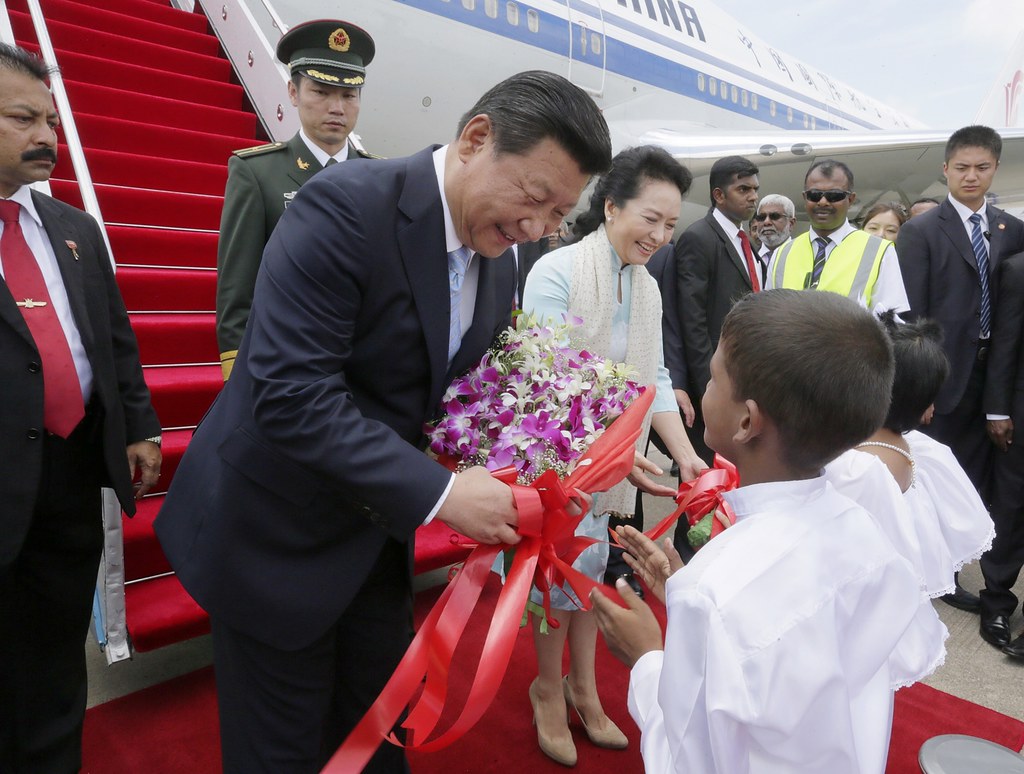

Image 1: Mahinda Rajapaksa via Flickr

Image 2: Mahinda Rajapaksa via Flickr