Introduction

China and India – both rising powers and nuclear-armed states – are locked in an intensifying security dilemma. China seems to have the upper hand given its larger economy, more advanced military-modernization program, and burgeoning economic and political clout in India’s neighborhood, as exemplified by the Belt and Road Initiative. Further exacerbating tensions between the two countries are countervailing strategic partnerships – China with Pakistan and India with the United States – and maritime competition in the Indian Ocean.1

Yet, the biggest source of friction remains the ongoing dispute over the Sino-Indian frontier and the related problem of prolonged standoffs along the Line of Actual Control (LAC).2 Clarifying and respecting the LAC – and, at a later date, formally resolving the boundary issue – are in the economic, political, and strategic interests of both countries. If the LAC remains contested, both sides are likely to experience squandered economic gains; disruptive, exogenous shocks to domestic politics; and strategic distraction. The most extreme consequences of a failure to clarify and respect the LAC could include an uptick in militarized crises replete with escalation dangers, and, potentially, a border war that could hamper China and India’s upward trajectories in the 21st century.

Many have observed that China and India have not had a single shooting incident along the de-facto boundary – the LAC – since 1967, when the two sides faced off at Nathu La. The avoidance of kinetic exchanges along the LAC for more than half a century is a remarkable achievement, but this narrative is not reassuring given a major military confrontation at Sumdorong Chu in 1987 and prolonged standoffs at Ladakh in 2013 and 2014. The persistence of incursions along the LAC – combined with open-ended road-building and militarization on both sides of the line – are among the trends that suggest a greater potential for friction and escalation along the LAC in the future.

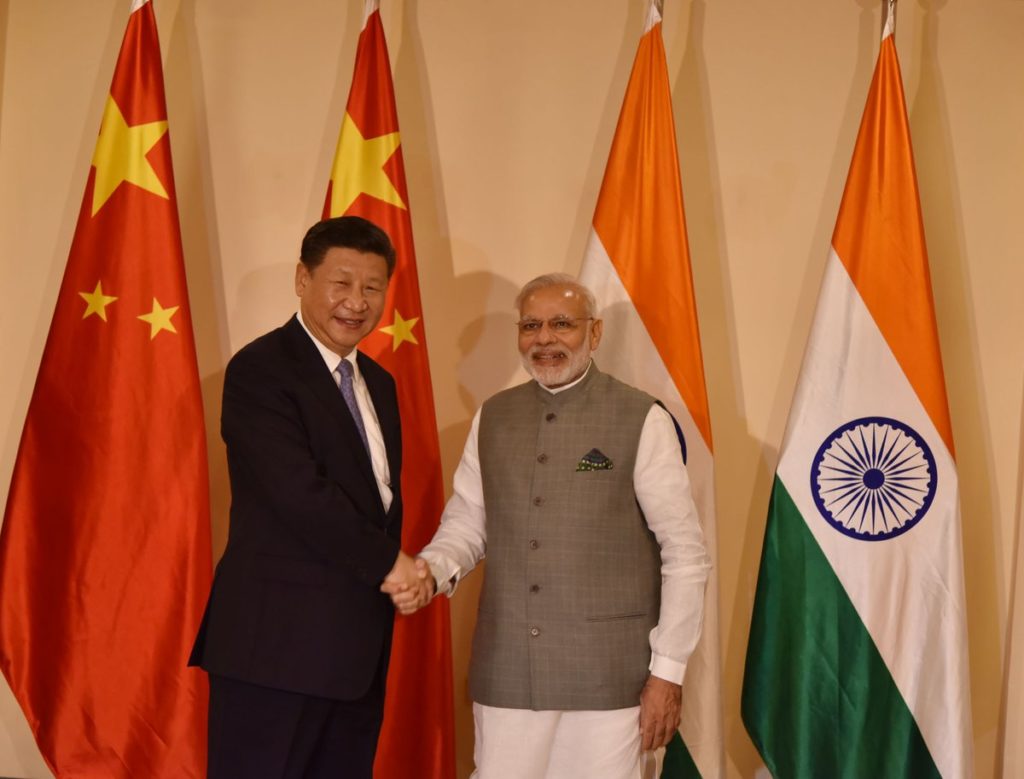

Chinese and Indian leaders seem increasingly cognizant of escalation dangers along the LAC, but neither side is doing enough to prevent protracted confrontations from happening, and both remain unreasonably confident in their ability to manage incidents when they do occur. At the Wuhan Summit in April 2018, Chinese President Xi Jinping and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi reiterated their support for a “reasonable and mutually acceptable settlement” of the boundary dispute, tasked their militaries with “strengthen[ing] existing institutional arrangements and information-sharing mechanisms to prevent incidents in border regions,” and reportedly agreed to set up a new military-to-military hotline.3 These are welcome steps, but disturbing events along the LAC are likely to persist so long as the underlying condition – an unclarified LAC conducive to regular charges of violations – remains unaddressed. If Xi and Modi are serious about ameliorating tensions and reducing the potential for miscalculation, then clarifying and respecting the LAC – an endeavor China and India decided to undertake in 1993 and 1996,4 and which this essay recommends – is a precondition for success.

Sino-Indian Disputes: The Boundary and Tibet

China and India dispute the alignment of the Sino-Indian boundary in two of three sectors: the western sector (Indian-administered Kashmir and the Chinese provinces of Xinjiang and Tibet) and the eastern sector (the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh and Tibet). In the western sector, the dispute revolves around 38,000 square kilometers known as Aksai Chin, which India claims but China administers as a result of an agreement with Pakistan in 1963.5 In the eastern sector, China claims 90,000 square kilometers of Indian territory, including significant areas of Arunachal Pradesh, which it refers to as “Southern Tibet.” 6

British maps at the time of the 1947 partition of the Indian subcontinent showed the western sector as “undefined.” Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru argued that the sector was defined “chiefly by long usage and custom.” 7 In 1954, India published revised maps that asserted an expansive claim line – the Johnson-Ardagh Line, which the British had proposed to the Chinese in 1899 – extending the Indian frontier in the western sector to the Kunlun Mountains.8 In the eastern sector, India insisted that the boundary corresponded with the crest line of the eastern Himalayas and was delimited by the McMahon Line, which had been endorsed at the 1914 Simla Convention involving British, Chinese, and Tibetan representatives.9 These claims aside, at the time of independence India exercised little administrative control in its northeastern territories near the McMahon Line, a ground reality that Indian forces began to redress with seizure of the Buddhist enclave of Tawang from Tibetan authorities in 1951.10

As the 1950s progressed, Indian leaders became progressively concerned that their Chinese counterparts did not share their conception of the Sino-Indian frontier. When pressed, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai placated Nehru with assurances that Chinese maps depicting large swaths of Indian territory as part of China were outdated.11 Zhou also hinted that China viewed the McMahon Line as an “accomplished fact.”12 These comments lulled Nehru into thinking there were no major disputes along the Sino-Indian boundary, but subsequent events suggested otherwise. In 1957, China announced it had constructed a highway linking Xinjiang with Tibet,13 reinforcing its military position in Tibet. An Indian patrol subsequently confirmed that the Chinese road traversed Aksai Chin, 14 prompting India to issue a formal protest to China.15 Around the same time, China published maps depicting vast swaths of India’s northeastern frontier as Chinese territory.16 In an exchange of letters between Nehru and Zhou in 1958 and 1959, the Chinese premier emphasized the boundary’s undefined nature, contended that Aksai Chin was part of China, and dismissed the McMahon Line as an illegal artifact of British imperialist aggression and subterfuge.17

Zhou’s stance on the boundary dispute was grounded in China’s past experience of “national humiliation” and its ideological opposition to imperialism. Similar considerations had factored into China’s 1950 invasion of Tibet. Chinese leaders viewed an independent Tibet as a potential source of foreign provocations. Consolidating their control of Tibet would enhance internal security in addition to restoring full sovereignty over a former tributary state and removing a “scar” of British imperialism. 18 Even after India repudiated British policy toward Tibet by explicitly recognizing Chinese sovereignty over the Himalayan region in the 1954 Panchsheel Agreement, China regarded Indian advocacy for Tibetan autonomy and against the burgeoning Chinese military presence with great suspicion.19 When Tibetans staged an armed uprising against Chinese rule in the late 1950s, Chinese leaders presumed an Indian hand in the violence. Beijing regarded New Delhi’s subsequent decision to let the Dalai Lama form a government-in-exile as confirmation of their worst fears.20

With tensions mounting over the Sino-Indian frontier and Tibet’s status, Zhou met with Nehru in 1960 and put forth a “package proposal” for resolving the boundary issue. As part of this proposal, China pledged to relinquish its claims in the eastern sector contingent on India’s willingness to renounce its claims in the western sector and cede Aksai Chin.21

Nehru rejected the proposal as a result of internal political opposition and legal constraints as well as a principled conviction that India should not capitulate to Chinese “cartographic aggression.” 22 China perceived Nehru’s refusal of a swap – coupled with India’s “forward policy” that entailed a combination of forward military posts and active patrolling along the disputed border – as fundamentally threatening China’s hold over Tibet.23 In response to India’s forward policy, Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong ordered the Chinese to pursue a policy of “armed coexistence,” which involved establishing localized superiority and occupying “commanding heights” to encircle and isolate Indian positions across the disputed frontier.24 Skirmishes ensued throughout 1961 and 1962, setting the two Asian powers on a collision course toward war.

In October 1962, Mao concluded that “little blows” had failed to hamper India’s forward policy and ordered the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to launch a “fierce and painful” attack.25 In the eastern sector, the PLA crossed the McMahon Line, routed the Indian Army, and seized several disputed areas, including Tawang.26 After approximately a month of fighting, China declared a unilateral cease-fire.27 The PLA relocated its forces to pre-war positions on the Chinese side of the McMahon Line. In the western sector, however, the PLA did not vacate territories captured during the war, which extended to the Karakoram Mountains and encompassed Aksai Chin.28 These new Chinese positions, which spanned 320 kilometers of the western sector, came to be known as the LAC, terminology that was expanded to include the entire disputed boundary – including the middle and eastern sectors – in confidence-building measures (CBMs) negotiated in the 1990s.29

For the first decade and a half that followed the 1962 conflict, China and India focused on domestic priorities, and neither country patrolled the LAC with any vigor.30 Both sides began patrolling the LAC more closely in the mid-1970s as China further consolidated its military position in Tibet and as India founded a China Study Group, which sanctioned a more robust military posture along the LAC.31 Military patrols – gradually reinforced by infrastructure enhancements – once again became the preferred means by which the two countries asserted their conflicting, overlapping claims. These dynamics fostered the conditions that led to the confrontation at Sumdorong Chu in 1987. By the early 1990s, the Chinese and Indian militaries were in close contact at critical locales along the LAC, and Beijing and New Delhi were more and more conscious of the need to dampen escalation prospects along the disputed boundary.

The Proposal

It is time for Beijing and New Delhi to move forward with their mutual commitment to clarify and respect the LAC, even if formal settlements of the boundary dispute and the Tibet question remain distant prospects. The first step in this proposal – delimitation – would begin with an exchange of maps, which would reveal each side’s perception of the LAC’s alignment in the western, middle, and eastern sectors. The delimitation phase would conclude with mutual endorsement of the status quo along the LAC and mutual recognition of the line’s precise alignment. A demarcation phase would follow during which the Chinese and Indian militaries would take additional steps to demarcate and respect the LAC on the ground while strictly observing and faithfully implementing existing CBMs.

New Delhi differentiates between transgressions and incursions in defining violations of the LAC, a useful distinction for this analysis.32 Transgressions are defined as accidental violations and are minimized as inevitable, minor incidents resulting from an undemarcated boundary and “localized” disputes.33 Incursions, by contrast, are characterized as calculated violations of the LAC.34 The intentionality behind such acts equates incursions with tests of resolve. The utility of a clarified, respected LAC would lie in part in the reduction of unintentional transgressions, but also, more importantly, in the avoidance of intentional incursions that generate prolonged standoffs, escalation dangers, and a host of economic, political, and strategic problems for the two countries.

Supporting Rationale

Clarifying and respecting the LAC – and, at a later date, formally resolving the boundary issue – are in the economic, political, and strategic interests of both countries. If the LAC remains contested, both sides are likely to experience squandered economic gains; disruptive, exogenous shocks to domestic politics; and strategic distraction. The most extreme consequences of a failure to clarify and respect the LAC could include an uptick in militarized crises replete with escalation dangers, and, potentially, a border war that could hamper China and India’s upward trajectories in the 21st century.

The 1987 Sumdorong Chu incident highlights the perils of protracted confrontations along the LAC. The crisis began in May 1986 when an Indian army patrol discovered that the PLA had taken over an Indian observation post in the Sumdorong Chu Valley, which is located near the Thagla Ridge north of Tawang in Arunachal Pradesh.35 China insisted that the post it had occupied was north of the McMahon Line whereas India, which had manned the post since 1984, claimed the opposite.36 In a bid to de-escalate the situation, India suggested it would not reclaim the post the following summer if both sides withdrew their forces.37 China refused to budge, and Deng Xiaoping warned that it might be necessary to “teach India a lesson.” 38 The crisis intensified in March 1987 when the Indian army initiated a massive, China-centric military exercise called Operation Chequerboard and the PLA mobilized additional forces, including more than 20,000 soldiers, into Tibet.39 Both the Soviet Union and the United States pressured the two countries to de-escalate the crisis, a process that began in August 1987 but remained unresolved until China and India agreed to withdraw from the valley in April 1995. 40

One virtue of this proposal to clarify and respect the LAC is that it envisions the effective implementation of existing CBMs and agreements rather than the arduous negotiation of new accords. A flurry of CBMs were achieved during a period of rapprochement in the 1990s that followed Sumdorong Chu and New Delhi’s decision to de-link progress in Sino-Indian relations from boundary issues. Through the 1993 Border Peace and Tranquility Agreement, China and India agreed to abjure the use of force in resolving the boundary dispute, respect the status quo along the LAC, and reduce military forces in the LAC’s vicinity on the basis of “mutual and equal security.” 41 In 1996, the two sides signed the Agreement on Confidence-Building Measures in the Military Field along the Line of Actual Control, in which they committed to refrain from military activities near the LAC with high escalatory potential – such as large-scale military exercises – and establish communication channels between military headquarters near the LAC.42

China and India reached additional understandings on the boundary after the turn of the century. During Indian Prime Minister A. B. Vajpayee’s 2003 trip to China, Beijing and New Delhi decided to resume cross-border trade at Nathu La – a trading post between Tibet and India’s northeast that witnessed deadly skirmishes in 1967 – and empower special representatives with achieving an “agreed framework” to settle the dispute.43 In 2005, the two sides negotiated political parameters and guiding principles for solving the boundary question, which called on them to devise “meaningful and mutually acceptable adjustments to their respective positions on the boundary” and to “respect and observe” the LAC pending its clarification. Later that year, China and India signed yet another CBM that elucidated standard operating procedures (SOPs) for military conduct along the LAC, which was intended to reduce friction between forward patrols.44 The Border Defense and Cooperation Agreement was concluded in 2013, which required both countries to avoid the escalatory tactic of “tailing” the other side’s military patrols that had inadvertently crossed the LAC.45

These CBMs have had a mixed track record. While specific measures – such as instituting SOPs that govern military interactions – may curtail escalation dangers resulting from accidental transgressions, the ongoing occurrence of protracted standoffs along the LAC suggests that the Sino-Indian CBM regime may be insufficient to prevent militarized crises and to manage escalation resulting from intentional incursions. As Manoj Joshi has recognized, “ … instead of bringing down military competition, [the CBM regime] is seeking – somewhat pointlessly – to cope with it … [CBMs] can promote restraint and reduce the risk of confrontation and war, but they cannot entirely eliminate them.” 46 Clarifying and respecting the LAC – as China and India have agreed to do numerous times – is one of the few CBMs that could diminish both the outsized burden on the CBM regime and the occurrence of protracted standoffs with escalation potential. Implementing this proposal would require the Chinese and Indian militaries to forswear the use of cross-LAC incursions as coercive tools to alter the status quo. For that reason, it could also revive interest in “mutual and equal security,” a principle enshrined in the Border Peace and Tranquility Agreement that could curb the LAC’s open-ended militarization.47

Potential Challenges

There are several potential challenges to this proposal for both China and India.

First, this proposal is likely to contradict the strategic impulses of many in Beijing and New Delhi who are confident that the wisest course is to defer the LAC’s clarification until military advantages translate into political leverage at the negotiating table. As former Indian Foreign Secretary Shivshankar Menon has pointed out, “The fundamental reason the boundary settlement is taking so long … is that both sides think that time is on their side, that their relative position will improve over time.” 48 This thinking is misguided. Escalatory pressures – ranging from the two militaries being in more proximate, frequent contact to the ongoing development of military infrastructure and the deployment of dual-use platforms in the disputed boundary’s vicinity – are on the rise, making escalation risks more severe than in the past.49 Moreover, the longer a political decision to resolve the boundary dispute is deferred, the greater the risk that sustained crises resulting from cross-LAC incursions could harden political opposition to compromises in a final settlement and could cause both sides to resist negotiated outcomes that fail to deliver on maximalist demands. A final problem with the logic of deferment is that the utility of force along the LAC is likely to decline as the costs of military conflict between China and India increase, partially mitigating the negotiating advantages that either side could gain from relative power differentials.

Second, China appears loath to enshrine the status quo along the LAC because it would prefer the resolution of the boundary dispute on its terms.50 Shifts in Chinese attitudes became apparent in the mid-1980s when China retracted the so-called package proposal, identified the eastern sector as the “biggest dispute,” and demanded the inclusion of Tawang in an eventual settlement.51 Three decades after the initial signs of trouble, China’s opposition to the status quo has intensified. Beijing’s insistence on incorporating Tawang into China has torpedoed discussions between the special representatives.52 The “pockets” of dispute along the LAC have more than doubled, from eight to 20, since 1995.53 As these disagreements have come to the fore, China has soured on the LAC’s clarification via the exchange of maps and prefers a more limited “code of conduct,” which the Indian side has rejected.54

Third, Beijing still views the boundary dispute through the prism of the Tibet question and is likely to forgo policies – such as delimitation and demarcation of the LAC – that could limit its options should New Delhi attempt to play the Tibet card. New Delhi has repeatedly stated that it regards Tibet as an “autonomous region of China” and promised to prohibit “anti-Chinese political activities by Tibetan elements” in India. Yet, developments have heightened Chinese anxiety. The Dalai Lama declared in 2008 that Tawang was an “integral part of India,” and New Delhi facilitated his visit to the Buddhist enclave in Arunachal Pradesh the following year.55 The Dalai Lama’s 2011 renunciation of political leadership of the Tibetan government-in-exile and the subsequent electoral victory of Lobsang Sangay – a charismatic leader who has proven willing to criticize China – perturbed Beijing.56 Another source of potential discord in Sino-Indian relations is the impending succession of the Dalai Lama. In response to indications that Beijing might try to co-opt the succession process, the octogenarian Dalai Lama has announced he will choose his successor via “emanation,” which means the next Tibetan spiritual leader will be found outside China.57

Fourth, there is considerable evidence that Beijing conceives of the unclarified LAC as a source of coercive leverage vis-à-vis New Delhi. Chinese transgressions have been increasing for much of the past decade.58 Recent Chinese incursions in the western sector at Depsang (2013) and Chumar (2014) may have been initiated to compel Indian forces to dismantle new posts near the LAC. Pressuring New Delhi to support a Beijing-backed freeze of military infrastructure along the disputed boundary – an agreement that would have entrenched Chinese advantages – may have been an additional rationale for Chinese actions in 2013.59 Close observers have concurred that Chinese interests lie in maintaining coercive leverage over India and “confin[ing] Indian strategic attention” to the disputed boundary. 60

Finally, Indian security managers might oppose proposals that could be perceived as jeopardizing their ongoing efforts to mitigate China’s military advantages along the LAC. In response to Chinese military infrastructure projects beginning in the 1990s, New Delhi sanctioned in 2006 a buildup of “strategic roads” near the contested boundary.61 In the ensuing years, India’s Cabinet Committee on Security authorized an upgrade of India’s military posture along the LAC to include the formation of a China-centric strike corps and two new infantry divisions in Arunachal Pradesh, the construction of advanced landing grounds, and the stationing of Brahmos cruise missiles.62 While India has done much to reduce power asymmetries along the LAC in the past decade or more, China appears to maintain the overall advantage, especially in terms of its military logistics network.63 Indian leaders may be loath to clarify and respect the LAC so long as such differentials persist.

Potential Benefits

China and India have a mutual interest in avoiding militarized crises or, at the extreme end, a second border war that could jeopardize economic growth, disrupt domestic politics, and engender negative strategic outcomes for both countries. Implementing this proposal could remove one of the persistent sources of bilateral tensions and a major potential catalyst of armed conflict – protracted confrontations along the LAC – with significant economic, political, and strategic benefits for both countries.

First, the Chinese and Indian economies could profit from stronger linkages, but tensions along the LAC and over other disputed territories have sabotaged repeated attempts to enhance the economic side of the relationship. As a result of the 2017 Doklam standoff at the Bhutanese-Chinese-Indian trijunction, Chinese foreign direct investment in India declined, with potential negative repercussions for the latter’s manufacturing sector. Cross-boundary trade at Nathu La was also disrupted during Doklam. Modi and Xi made an effort to surmount these barriers at the Wuhan Summit, with India seeking to reduce its trade deficit with China and China seeking new outlets – including greater access to the Indian market – to alleviate economic headwinds. The 2019 parliamentary elections in India may have further incentivized Modi to reach an accommodation at Wuhan to divert attention from the middling performance of the Indian economy under his watch.64

Second, stabilizing the LAC could create political benefits for Chinese and Indian leaders because such military confrontations impose real costs on their standing in domestic politics. China under Xi has undertaken various actions to bolster its strategic position in outstanding territorial disputes, moves that Xi regards as central to his personal legitimacy and the Communist Party’s political authority.65 Xi was reportedly eager to resolve Doklam because he worried it could undermine his legitimacy in advance of the 19th Party Congress.66 Moreover, new scholarship indicates that the Chinese public harbors hawkish attitudes on foreign policy, meaning domestic unrest is one possible outcome of an unsatisfactory military confrontation with a perceived weaker power such as India.67 Another related trend is the growing willingness of retired PLA figures to express their opposition to territorial concessions in public fora.68 These internal pressures help explain China’s advancing nationalistic narratives and publication of provocative warnings in state-controlled media during periods of aggravated threat perceptions, as occurred during Doklam. In India, skirmishes along the Sino-Indian frontier have low salience as an election issue, but extended showdowns have produced electoral effects and influenced elite debates and political jockeying at the parliamentary level.69

Third, both China and India could reap strategic rewards from greater stability along the LAC. Historically, three perceived vulnerabilities – domestic unrest, economic modernization, and challenges by the United States – have dominated the formulation of Chinese foreign policy. A genuine appraisal of these core threats has galvanized China’s pursuit of improved relations with its neighbors.70 By nurturing positive relations with powerful states on its periphery, Beijing has been able to reduce its overall strategic exposure, refocus on true foreign-policy priorities, and generate “room for maneuver” during perilous moments, such as the immediate aftermath of the Soviet Union’s collapse.71 Sino-Indian relations have often flourished under these conditions, which have coincided with progress on the boundary dispute.72

China’s assessment of the broader strategic environment – one in which it faces international opposition over the South China Sea and uncertainty with respect to its economy and relations with the United States – could cause it once again to deprioritize its disputes with India and reach further accommodations on the boundary.73 Such a shift could also attenuate Indian incentives for forging a well-functioning strategic partnership with the United States, removing from the board a major strategic challenge and potential barrier to China’s rise. For New Delhi, the strategic dividends of a clarified, respected LAC could be manifold and include a continued emphasis on economic growth, a defense budget with more funding for maritime capabilities, and preservation of its cherished strategic autonomy.

Conclusion

Chinese and Indian leaders appear overly confident in their ability to manage occasional flare-ups along the LAC.74 In reality, all militarized crises have an element of unpredictability over escalation control. Preventing a prolonged incursion along the LAC from escalating into an armed clash may be especially difficult if China and India are in the midst of a period of heightened tensions – as was the case in the years leading up to the Doklam standoff. Sidestepping escalation could also be challenging in circumstances where leaders fear they will incur high costs – either in terms of domestic politics or international reputation – for their failure to demonstrate sufficient resolve, dynamics to which China and India appear increasingly susceptible as the two compete for influence and power in the 21st century.

As China and India negotiated the Border Peace and Tranquility Agreement and subsequent CBMs in the 1990s, there was a mutual recognition that the LAC was the “basis of the peace.”75 Such a recognition is needed today. Clarifying and respecting the LAC would help ward off devastating conflict between China and India, inoculate the bilateral relationship from LAC-related disruptions, and facilitate economic, political, and strategic imperatives of both countries. It is therefore an “off ramp” worth taking.

Editor’s Note: This essay is part of a new Stimson Center book, Off Ramps from Confrontation in Southern Asia, and has been republished with permission. The book features pragmatic, novel approaches from rising talent and veteran analysts to reduce tensions resulting out of nuclear competition among India, Pakistan, and China. The full book is available for download here.

Image 1: Good Free Photos

Image 2: Narendra Modi via Flickr

***

- For a variety of perspectives on these evolving strategic dynamics, see Sameer Lalwani, Usha Sahay, and Travis Wheeler, eds., “Southern (Dis)Comfort” series, War on the Rocks, accessed December 1, 2018, https://warontherocks.com/category/special-series/southern-discomfort/.

- Manoj Joshi, “The Wuhan Summit and the India-China Border Dispute,” ORF Special Report (New Delhi: Observer Research Foundation, June 2018), 2 and 14.

- Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, “India-China Informal Summit at Wuhan,” April 28, 2018, accessed December 1, 2018, https://mea.gov.in/press-releases.htm?dtl/29853/IndiaChina_Informal_Summit_at_Wuhan; and Frank O’Donnell, “Stabilizing Sino-Indian Security Relations: Managing Strategic Rivalry after Doklam” (Beijing: Carnegie-Tsinghua Center for Global Policy, 2018).

- In CBMs signed in 1993 and 1996, respectively, China and India recognized the entire disputed frontier as the LAC in addition to pledging to respect the LAC, reduce its militarization, and clarify its alignment. For an accounting of these agreements, see Susan L. Shirk, “One-Sided Rivalry: China’s Perceptions and Policies toward India,” in The India-China Relationship: What the United States Needs to Know, ed. Francine R. Frankel and Harry Harding (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 81.

- John W. Garver, Protracted Contest: Sino-Indian Rivalry in the Twentieth Century (Seattle: University of Seattle Press, 2001), 79.

- Ibid. There is some disagreement regarding the extent of Chinese claims in the eastern sector. For a full discussion of these discrepancies, see Shyam Saran, How India Sees the World: Kautilya to the 21st Century (New Delhi: Juggernaut, 2017), 124; and Jeff M. Smith, Cold Peace: China-India Rivalry in the Twenty-First Century(Lanham: Lexington Books, 2014), 26-28, Kindle.

- Srinath Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India (Ranikhet: Permanent Black, 2010), 228-229 and 235.

- Saran, How India Sees the World, 125-126.

- Garver, Protracted Contest, 79; and Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India, 229 and 235.

- Smith, Cold Peace, 76-77.

- Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India, 243.

- Zhou was referring solely to the part of the McMahon Line that covered the Sino-Burmese boundary, but Nehru appears to have interpreted his statement to apply to the McMahon Line as a whole. See Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India, 245.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 247.

- Saran, How India Sees the World, 132.

- Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India, 246.

- Ibid., 248.

- Garver, Protracted Contest, 33-36; and Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India, 237.

- Garver, Protracted Contest, 43-53.

- Smith, Cold Peace, 86.

- Sumit Ganguly, “India and China: Border Issues, Domestic Integration, and International Security,” in The India-China Relationship: What the United States Needs to Know, ed. Francine R. Frankel and Harry Harding (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 112.

- Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India, 262.

- The policy goal of Nehru’s forward policy was to improve Indian awareness of the burgeoning Chinese presence near contested areas as well as to deter Chinese forces from advancing closer to their claim lines. Guidance issued by the prime minister and his advisors in November 1961 called for the “effective occupation of the whole frontier,” but instructed the Indian Army to avoid clashes except in self-defense. For an in-depth discussion of the “forward policy,” see Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India, 275-76 and 282-83; Reflecting on the 1962 Sino-Indian War, Mao Zedong reportedly acknowledged, “The main problem [in Indian-Chinese relations] is not the problem of the McMahon Line, but the Tibet question.” This interpretation stemmed, in part, from Mao’s belief that India had embraced an “imperialist strategy” of the British and sought to maintain Tibet as a buffer state. See Garver, Protracted Contest, 59.

- Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India, 285-87 and 292-98.

- Ibid., 298-99.

- Saran, How India Sees the World, 130-31.

- Ibid.

- Pravin Sawhney and Ghazala Wahab, Dragon on Our Doorstep: Managing China Through Military Power (New Delhi: Aleph, 2017), 41.

- For an interesting exploration of differing Chinese and Indian perspectives on the phraseology and legal significance of the Line of Actual Control (and how these perspectives played out in negotiations over bilateral CBMs), see Shivshankar Menon, Choices: Inside the Making of India’s Foreign Policy (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2016), 13-14 and 18-19.

- Menon, Choices, 13; and Joshi, “The Wuhan Summit and the India-China Border Dispute,” 10.

- Menon, Choices, 14; and Joshi, “The Wuhan Summit and the India-China Border Dispute,” 11.

- China does not report on Indian transgressions or incursions along the LAC.

- Fayaz Bukhari, “Chinese Troops Camping in ‘Indian Territory’: Police,” Reuters, April 20, 2013, accessed November 10, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-china-idUSBRE93J09620130420; and Gardiner Harris and Edward Wong, “Border Dispute between China and India Persists,” New York Times, May 2, 2013, accessed October 1, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/03/world/asia/where-china-meets-india-push-comes-to-shove.html.

- Smith, Cold Peace, 46.

- Sushant Singh, “Why 2017 Is Not 1987,” The Indian Express, August 4, 2017, accessed November 30, 2018, https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/doklam-standoff-india-china-army-troops-war-bhutan-4781309/; and Garver, Protracted Contest, 97.

- V. Natarajan, “The Sumdorong Chu Incident,” Bharat Rakshak, October 12, 2006, accessed November 30, 2018, https://www.bharat-rakshak.com/ARMY/history/siachen/286-Sumdorong-Incident.html. For more on the origins of the disagreement over Sumdorong Chu’s location with respect to the McMahon Line, see Menon, Choices, 15.

- Singh, “Why 2017 Is Not 1987.”

- Ibid.

- Garver, Protracted Contest, 97.

- Ibid; V. Natarajan, “The Sumdorong Chu Incident.”

- Susan L. Shirk, “One-Sided Rivalry,” in The India-China Relationship, 81; and Joshi, “The Wuhan Summit and the India-China Border Dispute,” 4. For a detailed discussion of the Border Peace and Tranquility Agreement (1993), see Menon, Choices, 18-23.

- Shirk, “One-Sided Rivalry,” in The India-China Relationship, 81.

- Smith, Cold Peace, 36.

- Joshi, “The Wuhan Summit and the India-China Border Dispute,” 5.

- Ibid., 7.

- Ibid., 14.

- For more on the concept of “mutual and equal security” in the Border Peace and Tranquility Agreement (1993), see Menon, Choices, 20 and 25.

- Menon, Choices, 30.

- For a comprehensive treatment of rising escalation dangers between China and India, see Yogesh Joshi and Frank O’Donnell, India and Nuclear Asia: Forces, Doctrine, and Dangers (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2019), 91-103.

- Indian diplomats have concluded that the status quo along the LAC – plus minor adjustments – would be an appropriate basis for an eventual settlement, but concede that such a deal is improbable. See Saran, How India Sees the World, 144.

- Analysts have posited varied explanations for the expansion of Chinese claims in the eastern sector, including their emergence at the time of the Sumdorong Chu incident. The most convincing is that the “package deal” was no longer perceived as being in Beijing’s strategic interests because its position in Tibet depended more on incorporating Tawang into China than on accessing the region via the Xinjiang-Tibet Highway. See Garver, Protracted Contest, 104-106; and Saran, How India Sees the World, 140.

- Smith, Cold Peace, 39 and 47.

- Among the “pockets of dispute” in 1995 were Demchok and Trig Heights (western sector); Barahoti (middle sector); and Asaphila, Chantze, Longju, Namka Chu, and Sumdorong Chu (western sector). See Sawhney and Wahab, Dragon on Our Doorstep, 45. Locales that have been added to the list of disputed areas include Chumar, Depsang Bulge, Dumchele, Kongka La, Mount Sajun, Pangong Tso, and Spanggur Gap (western sector); Kaurik, Pulan Sunda, and Shipki La (middle sector); and Dichu and Yangste (eastern sector). See Joshi, “The Wuhan Summit and the India-China Border Dispute,” 3.

- Menon, Choices, 22; and Ananth Krishnan, “China Cool on LAC Clarification, Wants Border Code of Conduct,” India Today, June 4, 2015, accessed December 1, 2018, https://www.indiatoday.in/world/china/story/china-lac-narendra-modi-pok-south-china-sea-karakoram-highway-255522-2015-06-04.

- Smith, Cold Peace, 45 and 77.

- Ibid., 100-101.

- Most analysts believe the Dalai Lama’s success will be found in Tawang. See Ibid., 104-106.

- Alyssa Ayres, “China’s Mixed Messages To India,” Forbes, September 17, 2014, accessed October 5, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/alyssaayres/2014/09/17/chinas-mixed-messages-to-india/; and “Chinese Incursions into India Rose in 2017: Government Data,” The Times of India, February 5, 2018, accessed November 10, 2018, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/chinese-incursions-into-india-rose-in-2017-govt-data/articleshow/62793362.cms.

- Smith, Cold Peace, 49-50.

- Ibid., 58.

- Ibid., 40.

- Ibid., 41; and O’Donnell, “Stabilizing Sino-Indian Security Relations,” 6 and 10.

- O’Donnell, “Stabilizing Sino-Indian Security Relations,” 13 and 14; and Iskander Rehman, “Hard Men in a Hard Environment: Indian Special Operators along the Border with China,” War on the Rocks, January 25, 2017, accessed October 1, 2018, https://warontherocks.com/2017/01/hard-men-in-a-hard-environment-indian-special-operators-along-the-border-with-china/m.

- See Sameer Lalwani and Anubhav Gupta’s insights in Wuthnow et al., “One Year after They Almost Went to War, Can China and India Get Along?”

- See Oriana Skylar Mastro’s insights in “One Year After They Almost Went to War, Can China and India Get Along?”

- Tanvi Madan, “Doklam Standoff: The Takeaways for India,” Brookings Institution, September 4, 2017, accessed December 4, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/doklam-standoff-the-takeaways-for-india/.

- Jessica Chen Weiss, “How Hawkish Is the Chinese Public? Another Look at ‘Rising Nationalism’ and Chinese Foreign Policy” (abstract), Journal of Contemporary China, November 27, 2018, accessed December 4, 2018, https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3265588; and Edward Wong, “Q. and A.: Jessica Chen Weiss on Nationalism in Chinese Politics,” Sinosphere Blog, September 24, 2015, accessed December 4, 2018, https://sinosphere.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/09/24/china-nationalism-jessica-chen-weiss/.

- Garver, Protracted Contest, 107-108; and Smith, Cold Peace, 62.

- Vipin Narang and Paul Staniland, “Democratic Accountability and Foreign Security Policy: Theory and Evidence from India,” Security Studies 27, no. 3 (July 2018): 18-19; and Harris and Wong, “Border Dispute between China and India Persists.”

- The internal turmoil of the Great Leap Forward caused Chinese leaders to invoke the “Three Reconciliations and One Reduction,” which envisioned better relations with India, the Soviet Union, and the United States in addition to curtailing financial support for revolutions abroad. See Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India, 284; and Amrita Jash, “Mao Zedong’s ‘Art of War’: Perception of Opportunity versus Perception of Threat,” Manekshaw Paper (New Delhi: Centre for Land Warfare Studies, 2018).

- Chinese leaders’ fears of potential U.S. coercion were heightened during this period and contributed to the promulgation of the Twenty-Four-Character Strategy in which Deng offered the following advice to his contemporaries: “Observe calmly; secure our position; cope with affairs calmly; hide our capacities and bide our time; [and] be good at maintaining a low profile.” See Menon, Choices, 8 and 17-18.

- China ended support for insurgencies in India’s northeast in the late 1970s and resuscitated the “package proposal” in 1980 as part of a broader effort to forge an international environment conducive to economic growth. See Garver, Protracted Contest, 94 and 102.

- Even Xi’s China has proven willing to recalibrate its foreign policy when confronted by international opposition. The Wuhan Summit with India and agreements with Japan to pursue economic cooperation – including via BRI – and shelve territorial disputes in the East China Sea are two salient examples.

- For an Indian perspective on this issue, see Menon, Choices, 22.

- Menon, Choices, 22.