“I see nothing grand or impossible about our expressing our readiness for universal interdependence rather than independence…Nor have I slightest difficulty in agreeing that in these days of rapid intercommunication and growing consciousness of oneness of all mankind, we must recognize that our nationalism must not be inconsistent with progressive internationalism” – Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay.1

There is no universal feminist foreign policy blueprint. Different countries that have adopted a FFP framework have distinct goals imbibed in their approaches. This thus brings us to the question, what is feminist foreign policy? The Centre for Feminist Foreign Policy defines FFP as a political framework centering the wellbeing of those marginalized and that contests all forms of oppression emanating from forces of patriarchy, colonization, heteronormativity, capitalism, racism, imperialism and militarism, by offering an alternative intersectional reconceptualization of security from the vantage point of the most vulnerable.

Can there be a feminist foreign policy future for South Asia? The recent South Asian Voices series on feminist foreign policy in the region highlights the need for one and its potential scope. These include key arguments centering the ability of FFP to challenge existing patriarchal structures of power by filling gaps in traditional foreign policy approaches, promoting transitional justice in post conflict states, and stronger commitment to peace and gender inclusive policies, to name a few.

When examining South Asia and FFP, one must remember that the modern liberal state is a patriarchal institution, a “manly state.” It is a patriarchal institution cast in the gendered history of men’s domination in the public sphere, with the needs of women long being subjugated using the public/private divide. The challenge then lies in pursuing state-based channels to adopt tenets of feminist thought in international policy and practice.

One must remember that the modern liberal state is a patriarchal institution, a “manly state.”

Globally, there are several instances of progress where states have come on board to fight gender-based violence against women. These include the passing of landmark UN conventions like the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women (DEVAW) and the UN Security Council Resolution 1325. These are all products of feminist campaigns against gender based violence. Nonetheless, a tension remains with respect to what extent the feminist agenda can rely upon the very “institutions that are defined by masculine modes of action to challenge gender inequality.”

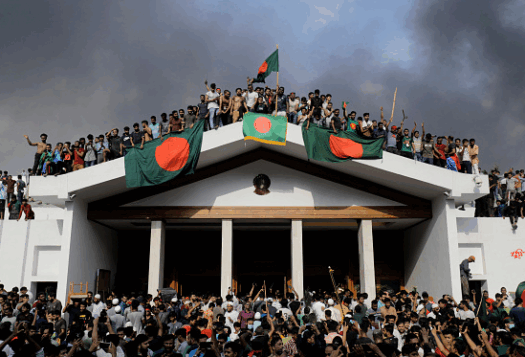

Understanding this tension is essential in envisioning possibilities of feminist foreign policy for South Asia as the rise of authoritarianism in the region and the deteriorating state of democracy continue to strengthen the patriarchal mold of the state. The pandemic has accelerated this process by providing governments smokescreens for draconian measures curbing civil liberties, dissent and increased state surveillance. The progressive erosion of democracy does not bode well for a feminist future. In pushing for a feminist foreign policy future for South Asia, feminist actors must also question the state of substantive democracy in the region: the fight for democracy and the fight for a feminist foreign policy are inherently synergistic.

Interrogating state power through feminism

FFP provides tools to contest “narrow nationalisms.” Hyper nationalist nation-states use a variety of instruments, invoking homogeneity, that attack the “other” to consolidate support of the majority group. In their zeal to penalize those not falling within this paradigm of “us,” hyper-nationalist states strip all those resisting its diktats of the very basic human rights guaranteed in a constitutional democracy. In their marches towards “greatness,” hyper-nationalist states flout every norm of dignified human existence.

The fight for democracy and the fight for a feminist foreign policy are inherently synergistic.

In foreign policy discourse, such acts of oppression are often covered under the lihaaf of Westphalian sovereignty. For example, as Dipti Tamang argues, when India commits to peacekeeping internationally while categorizing conflict within its own territory as “law and order problems” or “political disturbances,” thus denying the existence of the conflict. This denial dismisses both the conflict and its gendered consequences that remain hidden from the global policy discourse on Women, Peace and Security.

A FFP would contest this dismissal by calling for accountability, albeit sometimes with insistence at the expense of diplomacy because a “feminist foreign policy must be undiplomatic if it is to be transformative.” Any FFP ought to question such erasures and its architects need to become active interlocutors opening doors for women community leaders outside of the national capitals to join the conversation. This would include facilitating a robust feminist dialogue catering not to the state but to the promise of a feminist future that works towards dismantling all forms of masculine hegemonies.

Across South Asia, the trajectories of feminist confrontations with the nation states have been varied: this is a reflection of the uneven and distinctive trajectories of the region, as each state boasts its own particular postcolonial history. While in some countries, feminist interrogations of state power came earlier due to “the state and its links with fundamentalism” and armed conflicts that put feminists on ground in direct confrontation with the state, in others these contestations have taken time. This however does not erase strength and persistence of feminist resistance from the margins that has been challenging the “purity of nationalism” that often forms the edifice of national security. National security has also become a robust tool frequently used by majoritarian forces to silence voices of dissent. It is critical that any truly transformational vision of FFP incorporates voices marginalized by hyper-securitized, majoritarian state-making within its discourse.

Conclusion

Feminist foreign policy is not possible without feminist governance. It is crucial for the emerging South Asian FFP discourse to act with caution and perceive the state with skepticism. An effective FFP must go beyond simply bringing more women to the table—though that is a crucial part of the process. It must consciously examine the various hierarchies (caste, class, ethnic, regional, religious etc) that determine who has access to the table and which feminist voices are being left behind. It must push for active listening, and also consciously care for the silences that mar the state of foreign policy making dominated by elites.

Thus, South Asia’s roadmap for FFP must commit to addressing the coloniality of the postcolonial state and the excesses it continues to unleash on its most vulnerable populations. South Asia’s FFP cannot be a mere cosmetic dressing on old wounds. Rather, it must heal by radically transforming international relations as we understand them today. FFP should initiate dialogue on South Asian commons that is not bereft of commitment to accountability and care, not merely in the international forums but to the very people who the states claim to represent. Feminism cannot be a mere prefix to foreign policy. It is a verb, and thus should a Feminist Foreign Policy be.

***

Image 1: Mayank Makhija/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Image 2: Rehman Asad/NurPhoto via Getty Images

- Chattopadhyay, Kamaladevi in S.Radhakirshnan, et al., Mahatma Gandhi and One World, Govt of India, New Delhi, 1966, pp 11-12 ; Bhagavan, Manu, ‘Indian Internationalism and the Implementation of Self Determination’, in Ellen Carl DuBois and Vinay Lal (eds), A Passionate Life, Writings by and on Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, Zubaan, New Delhi, 2017.