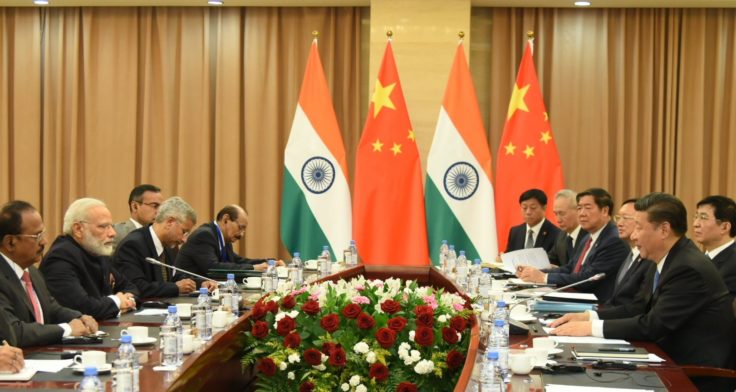

On the sidelines of the most recent BRICS Summit in Brazil, Chinese President Xi Jinping invited Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to visit China again in the new year. Xi also called for the two countries to expand cooperation and “increase political mutual trust.” The fact that a trust deficit has been recognized at the highest level of government is a good sign for China-India relations. Informal summits between Xi and Modi at Wuhan in 2018 and Mamallapuram in 2019—the so-called “Chennai Connect”—aimed to strengthen bilateral ties and fill the trust gap that followed the 2017 Doklam standoff.

However, if India and China truly wish to rebuild trust that has eroded over the past 70 years, both countries will need to engage constructively to begin to let go of mutual mistrust of each other’s strategic and economic objectives. Going forward in 2020, longstanding border disputes and a souring of relation over the trade deficit are the key irritants in India-China relations. Despite the incremental role summits may play in strengthening relations, these lingering issues still have the potential to frustrate bilateral relations and India will need to exercise deft diplomacy if it wishes to move the relationship away from one of mutual mistrust.

Despite the incremental role summits may play in strengthening relations, these lingering issues still have the potential to frustrate bilateral relations and India will need to exercise deft diplomacy if it wishes to move the relationship away from one of mutual mistrust.

Diplomatic Progressions and Regressions

In the aftermath of the Doklam standoff, Xi and Modi expressed their commitment at Wuhan to maintaining “peace and tranquillity” on the border for the sake of bilateral relations, with both sides noting the “the importance of respecting each other’s sensitivities, concerns and aspirations.” While India reported a decline in transgressions along the contested borders following the Wuhan summit; India and China are still far from a successful resolution of border issues. In 2019, however, it was not Doklam that spurred friction, but the Ladakh region of northwestern Kashmir.

As with other border disputes, the Ladakh issue has its roots in the British colonial era and the 1962 war, and has been the sight of skirmishes and standoffs. In 2019, these disputes came to the forefront again after India’s August 5 announcement that Ladakh and Jammu and Kashmir would be reorganized into two Union Territories. China followed with a statement condemning India’s unilateral undermining of China’s territorial sovereignty—urging India to exercise “prudence in words and deeds concerning the boundary question.”

India’s diplomatic efforts after the revocation of Article 370, including a visit by Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar to China where and assurances that the decision did not impact the Line of Actual Control, were apparently unsuccessful. Backing a request from Pakistan, China called for a closed-door meeting at the UN Security Council to discuss the Kashmir issue—the first since 1965. Kashmir also cast uncertainty on the Chennai summit, just a few days before Xi’s arrival, when the Chinese ambassador in Islamabad Yao Jing stated: “There should be a justified solution to the issue of Kashmir and China will stand by Pakistan for regional peace and stability.” India raised strong objections to the statement, which was viewed as a significant shift from the conventional Chinese position that India and Pakistan should resolve the issue bilaterally.

China’s position on Jammu and Kashmir seemed to fall between trying to corner India on the world stage and stopping short of siding with Pakistan. Neither is positive for India, but New Delhi should also avoid the overly ambitious expectation of China dramatically altering its historically held positions. While Indian diplomats have contained some of the fallout surrounding the revocation of Article 370, managing relations with China in regards to Kashmir will likely be an ongoing diplomatic task. After all, it took 10 years of diplomatic effort to get China to designate Masood Azhar as a global terrorist.

If India wants Chinese concessions on its concerns, such as Jammu and Kashmir or terrorism emanating from Pakistan, it should be prepared for sustained diplomatic heavy lifting. Respecting internal matters is a two-way street; perhaps this is the reason that the Indian government has refrained from mentioning in official communications what China considers internal concerns, namely the anti-government protests in Hong Kong or extensive human rights violations in Xinjiang province. India has even been quiet on maritime security issues in the South China Sea. However, while Kashmir was notably absent from discussions in Mamallapuram, questions of sovereignty will likely be an obstacle in China-India ties in the years to come. With India voicing displeasure over China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) projects it views as passing through its territory in Pakistan Administered Kashmir, and China continuing to refer to India’s current Kashmir policy as “unlawful and void.”

Economic Prospects

Despite promising deeper economic cooperation at the Strategic Economic Dialogue held earlier this year, India and China still have yet to resolve standing economic grievances. India’s burgeoning trade deficit with China has consistently been a sore point for New Delhi. Over the last five years, the trade deficit has grown from USD $48.5 billion to USD $53 billion. India’s Ambassador to China Vikram Misri has also stressed the importance of taking steps to address the “unsustainable” trade deficit lest it become a “politically sensitive” issue in India. Additionally, India’s top IT firms have often raised market access issues and complained about restrictions for business visas, mandatory compliance costs, and high taxes, all of which have limited Indian companies looking to invest in China.

Recently, India even walked out of signing the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a trade deal between 16 countries in the Indo-Pacific region whose members constitute about half of the world’s population and nearly 30 percent of global GDP. India’s concerns over an increasingly unfavorable trade deficit, exacerbated by the potential for RCEP to cause an influx of cheaper Chinese goods, and the trade deal’s lack of focus on service industry exports (which India has a comparative advantage in) may have driven India’s walkout. Despite reports of assurances from President Xi to Prime Minister Modi to alleviate Indian concerns, India did not sign the deal, indicating that the path to achieving mutual trust stretches beyond diplomatic assurances.

Despite the promises of both the Wuhan and Chennai summits to bolster economic cooperation, the trade deficit still seems to be a sticking point in China-India economic relations.

Both India and China have huge markets with immense potential to grow in the coming years. While India could learn from China’s manufacturing experience, India’s IT sector could contribute to China as it moves rapidly from a manufacturing to a service-based economy. Despite the promises of both the Wuhan and Chennai summits to bolster economic cooperation, the trade deficit still seems to be a sticking point in China-India economic relations. India, however, should be careful not to blame too much of its economic woes on China. For instance, despite moving up in the World Bank’s “ease of doing business” rankings, India has largely been unable to capitalize on economic opportunities from the U.S.-China trade war due to existing policy barriers.

Wuhan, Chennai, and Beyond 2020

To celebrate 70 years of diplomatic relations, India and China have designated 2020 as the “Year of India-China Cultural and People to People Exchanges”. Plans for 2020 suggest India and China are continuing down a path of visible partnership, as the two nations celebrate the milestone by organizing 70 activities “including a conference on a ship voyage tracing the historical connect between the two civilizations.”

However, 2019 has underscored areas of continued mistrust despite promises for greater bilateral cooperation. While some projects pursued after the Wuhan summit, such as jointly training Afghan diplomats, addressed some underlying trust issues, both countries need to push for cooperation in larger ventures. China’s closeness with Pakistan, such as China’s efforts to appease Pakistan by preventing India from pursuing large scale projects in Afghanistan, continues to drive wariness from India. For its part, India needs to show reasonable progress in projects like the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar corridor if it wishes to pursue a relationship with China independent from disputes with Pakistan.

Despite some ongoing frictions, the now potentially annual summits have made incremental gains in China-India cooperation and trust building. After Wuhan, these efforts contributed to a decline in border face-offs, and after Mamallapuram the two countries agreed to take steps to reduce the trade deficit by identifying sectors for mutual investment and joint manufacturing partnerships. In a year earmarked for celebration of diplomatic relations, it will be important to watch whether the Wuhan Spirit continues or if unresolved diplomatic and trade issues once again foster mutual distrust.

***

Image 1: Narendra Modi via Twitter

Image 2: Narendra Modi via Twitter (cropped)