The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (the Quad), comprising the United States, Japan, India, and Australia, reappeared on the international stage in November 2017 after a ten-year hiatus. The grouping immediately garnered attention because of two things: the impressive characteristics of its participants (the largest economy in the world and top military spender, the third-largest economy, the fastest-growing economy and second-most populous country in the world, and a significant middle power) and the timing of its rebirth (when Sino-U.S. trade and political conflict started heating up). Relations between China under Xi Jinping and the United States under Donald Trump were deteriorating rapidly in late 2017, and the reinstatement of the Quad was the first concrete step in the Trump administration’s strategy toward the Asia-Pacific region and the adjacent Indian Ocean (now renamed the Indo-Pacific strategy). At the recent Raisina Dialogue in New Delhi, a multilateral conference organized by the Indian foreign ministry, Admiral Phil Davidson, Commander of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, described the core of this strategy as advancing a free and open Indo-Pacific. But from the perspective of Russia, this strategy’s main goal is the containment of China and sabotage of Beijing’s efforts to reshape its surroundings in accordance with its increased capabilities and expanded interests. Though Moscow does not support all of Beijing’s initiatives and policies, it still sees China as a critical partner in its quest against the Western liberal order. Thus, Russia’s objections to the Quad are primarily driven by Chinese concerns. However, such a stance may alienate Russia’s traditional partner India and Moscow must recognize the costs of this.

Moscow’s reaction to the first meeting of the reinvigorated Quad, though negative, was very restrained: the concept behind the grouping was (and still is) too vague to make serious objections, but it was immediately perceived as contradicting Russia’s interests. There was no separate, public Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) statement on the Quad, but the idea of replacing the Asia-Pacific geopolitical construct with the Indo-Pacific was received in Moscow with little enthusiasm. Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Igor Morgulov called it an American strategy aimed at “drawing dividing lines” between countries. Aside from an inherent inclination to see all U.S. ideas as contrarian to Russia’s interests, there are several more cogent reasons why Moscow will likely never look at any positive aspects of the Quad or the Indo-Pacific concept as a whole (analysis of the Russian state-backed think-tank Valdai Club suggests that Russian authorities do not distinguish between the two, but perceive the Quad as a military axis within the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy).

Firstly, Moscow perceives the Quad as an anti-Chinese concept, devoid of any meaning apart from containing Beijing. The descriptions of a “free and open Indo-Pacific” put forward by Vice President Mike Pence at the Hudson Institute and U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis at the Shangri-La Dialogue as well as mentioned in the U.S. National Security Strategy are full of anti-China rhetoric. In addition, it is obvious that the unnamed country that various parts of the November 2017 Quad meeting agenda point to as contesting the participants’ values (such as upholding a “rules-based order” and “freedom of navigation” or infrastructure projects with “prudent financing”) is China. To be sure, Russia itself does not support some Chinese initiatives. For instance, although Russia officially pledges neutrality on the issue, Moscow’s adherence to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea indicates that it does not recognize the Chinese “nine-dash line” claims. Also, Russia has not really joined the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), preferring instead to “support” and “link” the BRI to its own initiative, the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU). However, Russia still perceives China as an important ally in its struggle for the multipolar world where countries have absolute sovereignty in domestic and external affairs and do not abide by a U.S. understanding of world politics. Moscow perceives any attack against Beijing as an attack against multipolarity, which in turn weakens Russia’s own stance.

Secondly, as Russian expert Anton Tsvetov has mentioned, the development of the Quad shifts the focus of Eurasian integration southward, which contradicts Moscow’s attempt to drag it northward through its Greater Eurasian Partnership. This is a loosely defined initiative with a goal to unite the Eurasian Economic Union, Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), and ASEAN countries with a network of free trade areas, technical standards harmonization treaties, and political consultation mechanisms. The idea was first announced in 2015, but few people outside Russia know about it even in 2019. Moscow is still struggling to find what it can offer to other potential participants as developing countries of Eurasia seek economic support, security, and (in an ever-growing number of cases) protection from a more assertive China. Moscow, unlike Beijing or Washington, can give none of these, and its nuclear umbrella appears to be useless in the low-intensity conflicts and territorial disputes of the region. In Moscow’s conception, this regional grouping does not conflict with BRI because of its orientation on soft infrastructure as opposed to hard infrastructure delivered by China. However, Russia’s leadership views the Quad as the core of a future competing U.S. project in the region akin to the Trans-Pacific Partnership but centered on security rather than trade.

Thirdly, Russia does not want to lose India as a friendly country and one of the biggest buyers of its defense equipment. India remains the world’s biggest arms importer and Russia accounts for 62 percent of its imports. The closer Delhi moves toward the United States, the worse the situation will become for Russia in this regard, as U.S. allies and strategic partners prefer to buy American weaponry. Additionally, Russia sees India as an important part of a multipolar world, actively engaging with it through the BRICS, RIC, and SCO regional forums, and would not like it to become an anti-Chinese or pro-Western power. Based on this author’s conversations with government officials, it seems that Moscow’s efforts in the coming years will likely be aimed at persuading Delhi that its choice of regional architecture should be the SCO or BRICS but not a United States-led Quad. Moscow believes that these institutions can guarantee India’s sovereignty and independence as well as provide mechanisms for peaceful resolution of its conflicts with neighbors, while U.S.-led bodies like the Quad will probably use Delhi as a battering ram against China.

Russia sees India as a weak link in this emerging grouping and will use all means possible to keep it from becoming a strong one. However, Russia’s options to dissuade India from deepening its engagement with the Quad are very limited. Regardless of what party wins the upcoming Indian election, the political priorities will always be economic development and maritime security, as well as protection from China. Russia’s economy is about the size of that of Spain; it cannot provide the investments India seeks. It also cannot provide security as Moscow has no Indian Ocean fleet. In the realm of ideology, Russia has nothing to match the “liberal world order.” But the most important reason why Moscow cannot convince Delhi to stay away from the Quad is because Moscow has absolutely no leverage over Beijing, and it cannot prevent China’s leadership from launching another Doklam offensive. Right now, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government in India tends to believe in engagement with Russia, tries to be constructive in dealing with China, and is reluctant to fully embrace the Quad agenda. But in the future, if China becomes even more assertive and prefers solving disputes with India in the realm of force rather than through dialogue or cooperating within the SCO/BRICS, the appeal of Russia-backed institutions may evaporate. In this case, India’s close engagement with the Quad will become much more probable, and without a strong Russian stance against China (which is highly unlikely), there is nothing Moscow can do to counter it.

***

Image 1: Zhang Lie/eng.chinamil.com.cn via Flickr Images

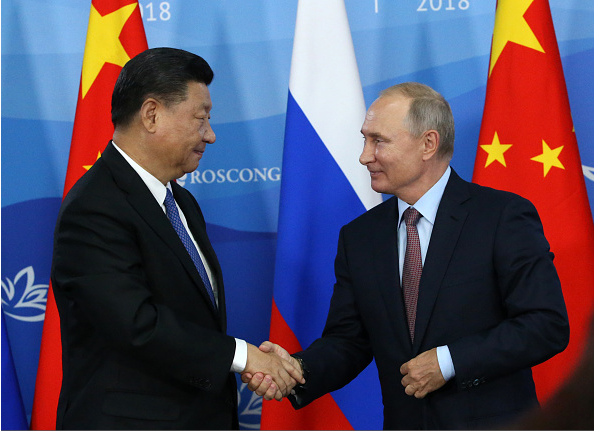

Image 2: Mikhail Svetlov via Getty Images