This week marks six months since the Indian government’s decision to withdraw Article 370 from Jammu & Kashmir, resulting in the removal of the erstwhile state’s autonomous provisions, and its reorganization into the Union Territories of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh. While some have supported this move, terming it as it the much-needed reintegration of Kashmir with the rest of India and a path towards stability in the region, others argue that this decision was enforced against the will of many Kashmiris and have criticized the government’s months-long communication blockade. In this two-part series, Aarti Tikoo Singh and Fahad Shah lay out the perspectives on both sides of this debate by responding to the following prompt: “Stable progress over the past six months suggests the political and security problems of Jammu & Kashmir are well on their way to being resolved with the Indian government’s actions post August 5. Agree or Disagree?” Read the entire series here.

***

Since the onset of Pakistan-sponsored militancy in Kashmir in 1989, a large section of Indian society has held the belief that apart from the security threat, the problem in Jammu & Kashmir (J&K) is political and that it needed to be resolved by New Delhi.

There were primarily two views on what constituted the political problem in Kashmir. One view was that the erosion of autonomy of the J&K state by the federal government over time caused alienation in the Kashmir Valley and led to militancy and the demands of “freedom” from India. This, however, did not explain why only the Valley, out of the entire state with three regions, erupted in violence and terrorism. Nor does this view explain why Kashmir continued to peacefully participate in large numbers in the electoral democracy of India until the rigged assembly elections of 1987 even as J&K’s autonomy was substantially eroded by successive governments in Kashmir and New Delhi through various legislation.

The answers to these questions are linked to the demographics of J&K and its political history since 1947, when India was partitioned and Pakistan was created on the basis of Muslim identity. Though Pakistan feels it has a claim to the state of J&K on the basis of religion, Kashmir is the only Muslim-majority region out of the three demographically-distinct and diverse regions that make up the erstwhile state. Pakistan, which has attempted to invade J&K four times since Partition, was able to find some support in the Muslim-majority Kashmir Valley only in the late 1970s-early 80s, when Islamabad shifted from a conventional to a sub-conventional strategy in the region. The prolonged Islamist militancy sponsored by Pakistan as well as India’s counterinsurgency operations combined with human rights violations created an abnormal state of affairs in J&K for the last three decades.

Even as Kashmir’s mainstream political parties swore allegiance to India, their base eroded as Pakistan’s proxies dominated the space with the help of the Islamist militancy and the use of religio-political discourse, particularly the slogan of “azadi” (freedom). To secure their vote bank, the mainstream political parties seemed to advocate for soft separatism by invoking the restoration of complete autonomy under Article 370, blurring the lines between the two camps.

The prolonged Islamist militancy sponsored by Pakistan as well as India’s counterinsurgency operations combined with human rights violations created an abnormal state of affairs in J&K for the last three decades.

The diluted Article 370 still derived substantial power from Article 35A, which authorized J&K to frame its own permanent residency laws. While every permanent resident of the former state of J&K enjoyed all the rights and privileges guaranteed under the Indian constitution, residents of other states could neither buy land nor avail any other benefits in J&K. Both the separatists and the mainstream political parties of Kashmir used the slogan of Article 370 to erect a religio-political wall between Kashmir and the rest of the country, often instilling fear that its abrogation was aimed at changing demographics of the Muslim-majority valley. However, neither the Hindu-dominated Jammu region nor the Buddhist-dominated Ladakh region have made any attempts to change the demographics of Kashmir in the last seven decades. In fact, often ignored is the ethnic cleansing of Kashmiri Hindus from the Valley.

This shaped the second view about the nature of the political problem in J&K—that autonomy to J&K had prevented Kashmir from integrating itself with the rest of India psychologically and hence, strengthened the sentiment of Muslim separatism.

On August 5, the Modi government made it clear that it gave credence to the second perspective, and thus reorganized the state resulting in the nullification of Article 370 of the Indian constitution, which had granted autonomy to J&K. The state was bifurcated into two Union Territories—Jammu & Kashmir (J&K) and Ladakh—and brought on par constitutionally with other parts of the country.

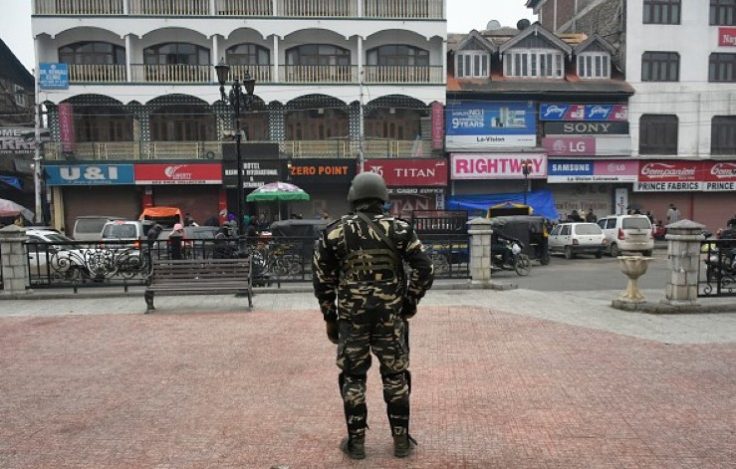

The government immediately placed the entire state under restrictions and a communication blockade and detained dozens of mainstream politicians and separatists. Many called the decision a unilateral imposition and the lockdown a human rights violation. However, this argument lacks merit because the Indian move needs to be understood in the context of thirty years of terror and violence that has corroded J&K, its institutions, and its society.

Over 45,000 people have been killed, 300,000 Kashmiri Pandits displaced, and hundreds of thousands injured in Pakistan’s proxy war fought by banned terror groups like Jaish-e-Mohammad, Lashkar-e-Taiba, and Hizbul Mujahideen in Kashmir. While cross-border terror continues, the new age Kashmir militancy, which began in the late 2000s, has relied heavily on stone-pelting, rioting, and arson. In 2016, massive violence broke out in Kashmir following the killing of Hizb commander Burhan Wani by Indian security forces in an encounter. Between 80 and 100 of those who had come out onto the streets to protest Wani’s death were killed in subsequent clashes with security forces. Global jihadi terror groups such as the Islamic State and al-Qaeda have also managed to find more traction in Kashmir with this new wave of militancy, establishing their own provincial branches in the region.

The Indian move needs to be understood in the context of 30 years of terror and violence that has corroded J&K, its institutions, and its society.

For any responsible and just state, the primary objective in such a scenario would be to protect the lives of its citizens. Though the internet restrictions have caused inconvenience and outrage, unlike previous instances when Kashmir erupted in violence over issues ranging from the 2008 Hindu Amarnath pilgrimage land row to the killing of Wani in 2016, the last six months in Kashmir have been relatively peaceful.

Security wise, the violence in Kashmir has declined by 2.7 times in the last six months compared to the previous six months. As per data compiled by the South Asian Terrorism Portal, from February to July 2019, 208 people were killed in Kashmir in several incidents of terror attacks and counterinsurgency operations. However, since August 2019 to January 2020, 77 people have been killed. Except for a handful of terror attacks, the valley has largely been stable.

Though the above statistics cannot definitively predict the future levels of violence in Kashmir, especially when the infiltration of terrorists from across the border has continued, what the data establishes is that there is a correlation between the reduction in violence and the preemptive measures that the government has taken, including internet restrictions, absence of social media, and detention of mobilizers of agitation in Kashmir.

The future security scenario in J&K will depend primarily on whether Pakistan changes its foreign policy vis-à-vis India and especially its cross-border terror strategy in Kashmir, and also on how New Delhi deals with variables like radicalization of youth in Islamic seminaries and mosques that practice extremist strains of Islam, and mobilization of violence using internet and social media in Kashmir.

Given emerging political trends, a third front, as a rival to the two main parties of Kashmir, seems to be a formidable possibility. However, these political formations still run the risk of being seen as puppets of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party government in New Delhi.

Politically, there has been a lot churn in Kashmir since August 2019. J&K has for the greater part of its history since 1947 been ruled by the two main political parties of Kashmir, the National Conference (NC) and the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), led by two prominent families, the Abdullahs and the Muftis respectively. Both parties have been severely critical of the Modi government over the nullification of Article 370 and Article 35A. Soon after the August 5 decision, dozens of Kashmiri politicians—including some who had threatened violence over the abrogation of Article 370—were held under preventive detention. Since then, barring 15 (including three former chief ministers), most of the politicians have been released. Out of this massive political disruption, at least three new political parties have emerged, with one headed by a former minister of the PDP. Given emerging political trends, a third front, as a rival to the two main parties of Kashmir, seems to be a formidable possibility. However, these political formations still run the risk of being seen as puppets of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party government in New Delhi.

For democracy to flourish organically in Kashmir, it is important for New Delhi to empower people at the lowest socio-economic levels across all sections of society. India’s panchayat (rural local self-governing bodies) system is democracy at the grassroots level. Panchayat elections were held in J&K in 2018. While 27,281 panches (members) and sarpanches (chiefs) were elected, another 12,776 panchayat seats have been vacant due to boycott of polls and militant threats. In October 2019, the elected panches and sarpanches elected their representatives for their respective 310 blocks. The by-elections to panchayats are likely to be held in March.

In its latest annual budget, the government has announced almost USD $5 billion for the development of the union territory of J&K. There are reports that India’s biggest business groups are also likely to invest in the state’s tourism, education, and health sectors. If the central government and private sector together build infrastructure, provide opportunities to J&K’s 12.5 million people, and ensure stability over the next five years or so, peace will not be far.

***

Image 1: Ronit Bhattacharjee via Flickr