Elections for India’s 18th Lok Sabha concluded smoothly on June 1, 2024. In Indian-administered Jammu & Kashmir (J&K), polling was held in five phases from April 19 to May 25 for the five constituencies of the region amid tight security arrangements. With a combined voter turnout of 58 percent, a 30-point increase from the previous parliamentary election, it was the “highest poll participation in the last 35 years.”

This high voter participation is significant. Unlike in 2019, when voters largely boycotted the Lok Sabha polls amidst violence and unrest, the Srinagar constituency witnessed a dramatic jump in voter turnout this time, going up from 14 percent to 38 percent. Baramulla and Anantnag-Rajouri witnessed even better polling numbers at 59 percent (34 percent previously) and 54 percent (eight percent previously – excluding seven assembly segments added later) respectively.

While the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has projected the relatively high voter turnout in J&K as a vindication of the Modi administration’s Kashmir policy, regional parties view it as a vote of dissent against the central government’s abrogation of Article 370, which terminated J&K’s enshrined autonomous status and split it into two centrally-controlled Union Territories. In any case, this heightened electoral mobilization has infused new life into Kashmir’s political landscape, which had shrunk after August 2019. This renewed political activity and the outcome of the 2024 polls will impact the upcoming J&K assembly elections – likely to be held by September this year – as well as the broader stability of the region.

Surveying the Landscape

Following the abrogation of Article 370 in 2019, some reports suggest that the last six years of continuous rule by New Delhi have made the people of J&K feel politically marginalized. The unelected and centrally-appointed Lieutenant Governor’s implementation of various laws have raised apprehensions among the public, not only in the Valley but also in Ladakh – which has been demanding constitutional protections of its distinct identity and ecologically-fragile province. The people of J&K view a centrally-run bureaucracy – where top administrative posts are helmed by non-local officials – as unattuned to local issues and sensitivities. In this context, Kashmir’s regional parties like the National Conference (NC) and the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), once labeled by Kashmiri separatists as New Delhi’s agents and collaborators, are now viewed as a representative voice, with elections being seen as a vehicle to express discontent. That is arguably why these parties have received wide support from the Valley in the current election cycle.

Kashmir’s regional parties like the National Conference (NC) and the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), once labeled by Kashmiri separatists as New Delhi’s agents and collaborators, are now viewed as a representative voice, with elections being seen as a vehicle to express discontent.

The Muslim-majority Kashmir Valley (6.9 million population), sends three members to the Lok Sabha (or the Lower House of the Parliament) while the Hindu-majority Jammu (5.3 million population) sends two. These regions have divergent views with respect to Center-State relations as well as regarding the region’s political future. The former seeks restoration of autonomous status whereas the latter, especially its Dogra Hindu belt composed of Jammu, Kathua, Samba and Udhampur districts, endorses merger with the Union. The 2024 poll outcome broadly reflects these conflicting regional interests. Jammu re-elected the incumbent BJP while Kashmir gave its mandate to the pro-autonomy NC and an independent candidate Abdul Rashid Sheikh, who fought from Delhi’s Tihar jail where he languishes under the draconian Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA).

While the PDP lost in all three Lok Sabha constituencies, its vote share jumped from 3.38 percent to 8.48 percent, raising hopes for the party’s prospects at the assembly elections later this year. Despite several defections from parties like the PDP, BJP-allied parties in the Valley performed poorly, with the Jammu & Kashmir Peoples Conference (JKPC) losing in its own stronghold of Baramulla. The Jammu & Kashmir Apni Party (JKAP) candidates lost their security deposits. The Democratic Progressive Azad Party (DPAP) was defeated in all the three constituencies it contested in. The poor performance of its allies in the Valley should force the BJP to rethink its strategy for the upcoming assembly polls in Kashmir, where the party remains unpopular due to its anti-Muslim image.

Implications for Assembly Elections

The Chief Election Commissioner has announced that assembly elections will soon be held in J&K for the first time since 2014, with the BJP likely to face a tough fight from both the Indian National Congress (INC) and the local parties. To feasibly form a government in J&K, the BJP will need support from the Valley’s local parties like the JKAP and the JKPC, who will compete against the NC and the PDP. The combined vote share of the NC and the PDP in the 2024 Lok Sabha elections was more than 70 percent in both Srinagar and Anantnag-Rajouri, two constituencies that compose almost two-thirds of the Valley’s 47 Assembly seats. The Awami Ittehad Party (AIP) of Engineer Rashid will also be a formidable player, since it established a lead in 14 assembly constituencies in the parliamentary elections. The Jammu region has 43 seats, for which the BJP will face contestation from the INC, the NC, the PDP, and smaller Jammu-based parties. While the BJP won the Udhampur Lok Sabha seat, its vote share dropped by ten percent while that of the INC’s increased by the same percentage. This trend will impact the assembly elections in Jammu, which will be a close contest between the INC and the BJP.

The BJP is likely to bank on its well-thought-out engineering strategy of gerrymandering and clientelistic politics to win the assembly election in the Hindu-majority Jammu. In 2022, the centrally-appointed Delimitation Commission redrew J&K’s constituencies such that Jammu’s seat-share increased by six. Two years later, Scheduled Tribe status was given to 1.6 million Paharis, about 56 percent of whom live in the Rajouri and Poonch districts of Jammu, where the BJP has also reserved nine assembly seats for STs for the first time. Soon after, a prominent Pahari leader Mushtaq Ahmad Shah Bukhari was poached by the BJP along with many of his supporters.

Through this strategic and social engineering, the BJP expects to garner a larger base of support in Rajouri and Poonch. The BJP did not contest the Lok Sabha elections in the Kashmir Valley, as the party said it needed to first build up its cadre there. However, the BJP has not been able to woo any political heavyweights to its side, even when regional parties have faced defections. The BJP’s only electoral success in the Valley so far has been winning three seats in the District Development Council (DDC), a 14-member locally elected body the central government introduced in 2020.

Local Politics Revived: Regional Implications

The BJP’s post-2019 promises of development have remained unfulfilled; investment has dropped, youth unemployment rate remains high at 18.3 percent, and political and civil rights have eroded as reported internationally. These grievances are likely to play against the BJP in the assembly elections. But more challenging for the incumbent national party will be managing the new wave of Kashmiri identity politics that has intensified after the revocation of Article 370. When the NC’s Ruhullah Mehdi won a Lok Sabha seat in Srinagar on June 4, he thanked his supporters by writing on X (formerly Twitter): “You have spoken democratically and spoken against the decisions of Aug 5, 2019.” This sentimental narrative, also echoed by the PDP and other parties, has set the tone for the upcoming and electorally significant Assembly Elections.

The BJP will simultaneously have to contend with the ‘Engineer Rashid wave’. Many youth and women came out and voted in the Lok Sabha elections in support of Rashid’s release from jail. Rashid – who straddles the middle ground between separatism and unionist politics – rose to prominence in the late 2000s, striking a chord with the public through his strong advocacy for human rights and autonomy for Kashmir. He won the Assembly election twice. But with his campaign catchphrase being “Jail ka badla vote se lenge” (We will avenge jailing with votes), a play on a popular slogan from the 2010 anti-India protests, the larger symbolism of Rashid’s campaign and eventual victory is clear. The vote for Rashid is seen as an articulation of soft separatism and symbolically, a support for thousands of Kashmiris incarcerated without trial since 2019. Rashid’s campaign drew first time and pro-boycott voters who moved away from the old separatist vanguard’s criminalization of poll participation, and reinterpreted voting as a form of resistance and political expression. Rashid described his thumping victory as a “referendum against all sorts of oppression against the people of Jammu & Kashmir.”

Adding to the changing political dynamics is the outlawed separatist political party Jamaat-e-Islami (JeI), which, sensing the changing mood on the ground, has put out feelers and indicated its readiness to re-join the electoral politics if unbanned. The JeI – whose assets have been seized by the government and its activities crippled – seeks to get the ban revoked and reestablish itself in J&K. The NC, which has had antagonistic relations with the JeI in the past, has supported lifting the ban on it this time.

The election is expected not only to push voter turnout even higher, but also to potentially bring elements of soft separatism back into the fold of electoral politics.

Pakistan, struggling with pressing domestic issues, has not commented on the election outcomes in J&K. Though former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, in a peace overture to India, called for replacing hate with hope. At the same time, however, the history of attacks in J&K playing a spoiler in India-Pakistan relations seems to be repeating itself; only the theater for proxy warfare has shifted from the Valley to Jammu. On the eve of Narendra Modi’s oath-taking for his third term, non-state armed groups launched four back-to-back attacks in Jammu, prompting high-level security meetings chaired by the Home Minister. The Resistance Front (TRF) and the People’s Anti-Fascist Front (PAFF), which Indian authorities believe to be fronts for Pakistan-based militant organizations Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammad, claimed responsibility for these attacks, only to retract it later. These attacks threaten to deteriorate the bilateral relationship already under stress since 2019.

Conclusion

The BJP’s loss of its parliamentary majority comes at a crucial time and provides new political opportunities to J&K. The party may be more restrained – including in its Kashmir policy – within the NDA coalition of secular parties. Amidst this new political environment, the upcoming Assembly Elections in September may be a point of paradigmatic shift in Kashmiri politics. The election is expected not only to push voter turnout even higher, but also to potentially bring elements of soft separatism back into the fold of electoral politics. This may have implications beyond the stability of the Union Territory. Pakistan will likely continue to observe how Kashmiris respond after the Assembly Election, with the counterinsurgency grid more engaged in Jammu and political space opening up due to renewed democratic processes and emerging leadership. Though India-Pakistan relations may remain largely unchanged, this transitional phase in J&K is likely to shape the future security and stability of the region.

Also Read: Indian Election Results Give Hope to Human Rights Organizations

***

Image 1: Voter Queue in Srinagar via Flickr

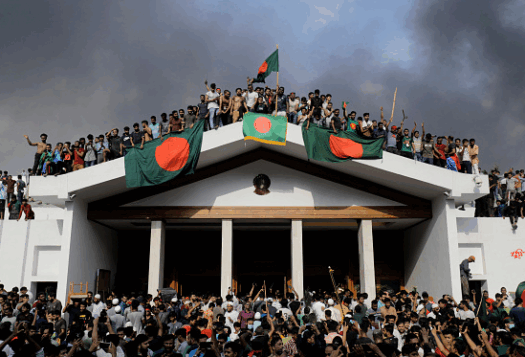

Image 2: Kashmir protest via Flickr