The 2020 Ladakh crisis between India and China, which began four years ago this spring, has had a larger impact on the relationship than expected. One of the notable trends in its aftermath is that India-China competition is no longer limited to the continental border but has a significant maritime dimension as well. Indian policymakers now publicly raise alarm about the noticeable surge in China’s naval and economic presence in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) in recent years and its implications for India’s national security. For New Delhi, the maritime domain is connected to its regional peace, security and growth. And thus, it has undertaken a multipronged approach to secure its maritime backyard, both by developing a network of partnerships as well as undertaking efforts to augment its naval presence in the region to deter any adversarial intervention or disruption. This competition has already had a cascading regional impact with the two countries seeking to extend their sphere of influence in the IOR in different ways. But the region is likely to witness further turbulence due to the competing visions of China on the one hand and India and the IOR countries on the other.

Indian Ocean Region in China’s Calculus

It is an economic imperative for China to engage with this demographically vibrant region with excellent trade prospects. This requires political support from the governments of the regional nations in order to gain market access and resources that are central to China’s growth. The Belt and Road Initiative is a key tool for achieving this, allowing the Chinese leadership to establish its geoeconomic and geopolitical presence beyond the South China Sea. Since the land Belt component is challenged by security issues or disputed borders across Asia, the maritime Road has become the backbone of the trade component as the seas are free and open for all. Though military presence is necessary to protect trade routes from pirates and other maritime challenges, Beijing’s approach of using dual use assets such as submarines and research vessels potentially for surveillance purposes is suspicious to policymakers and scholars alike. What’s more, when the pandemic forced countries to look inward and focus on domestic issues, creating a power vacuum in the global commons, China filled the gap.

Indian policymakers now publicly raise alarm about the noticeable surge in China’s naval and economic presence in the Indian Ocean region in recent years and its implications for India’s national security.

China has made inroads into the region in multiple ways. Strategically, it has put an enhanced focus on dual-use port presence and developing infrastructure such as submarine jetties in Cambodia, Myanmar and the Maldives, which Indian analysts see as a part of China’s ploy to encircle India. Militarily, China has increased its fleet number to more than 370 vessels, surpassing the United States. Additionally, it has elevated its partnership with India’s regional adversary Pakistan by providing it with eight advanced Hangor-class submarines fitted with air-independent propulsion technology, fueling the undersea arms race in the region. Not so incidentally, the submarines are named after PNS Hangor, the Pakistani diesel-attack submarine that sank the Indian frigate Khukri along with its Captain MN Malla in the 1971 India-Pakistan war. Such developments have stirred a debate in the Indian strategic community and more broadly on the logic and implications of Chinese actions in the IOR.

Fishing Fleets and Research Vessels as Strategic Assets

Besides upping its patrolling in the waters of the IOR, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has also sought to use fishing fleets and research vessels for potentially strategic purposes such as collecting sensitive data. In January 2020, the Indian Navy sighted a large Chinese fishing trawler accompanied by the PLAN outside India’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the Western Indian Ocean. A few other such sightings were reported that year. These incidents have not only raised concerns about the threat of illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing in the Indian Ocean region but also pose a potential national security issue as the boats switch off their automatic identification system (AIS) to prevent locational tracking near the EEZ or resort to AIS spoofing.

Another cause for concern has been the increasing presence of Chinese hydrographic survey and satellite tracking research vessels in the IOR that may be used as the “eyes and ears” of the PLA. Based on various reports and official Indian accounts, these vessels are capable of undertaking geological research, bathymetric data collection, seabed sampling and underwater current profiling, laying and maintenance of buoys, among other purposes. However, experts believe these vessels are fitted with sonars to collect undersea data required to track submarine movement and may also be capable of gathering missile-related data for military purposes. What fuels this belief is the timing of these vessels in the waters of the IOR—they usually come to wander in the eastern Indian Ocean whenever the Indian government releases a notice to the airmen (NOTAM) to clear the airspace in advance of missile testing or satellite launches in the Bay of Bengal region. These questionable maritime activities, reminiscent of China’s aggressive posture in the South China Sea, have caused concern about Chinese intentions in the IOR.

India’s Maritime Vision and Response to Threats

India’s maritime approach to the Indian Ocean is an extension of its foreign policy in the region, undergirded by the realization that its security and growth are linked with that of the IOR. Thus, in response to threats from China and to underline its commitment to protecting its interests in the maritime domain, the Indian Navy has adopted a three-pronged approach: bolstering its presence in the region, enhancing extra-regional partnerships to benefit the IOR, and developing regional capacity through its indigenous defense program.

Since 2018, the Indian Navy has been doing mission-based deployments in the Indian Ocean, ensuring round-the-clock presence of its ships around eight crucial entry points of the ocean. Whether through rescue and relief operations during regional disasters or thwarting attempts at re-emerging piracy in the Western Indian Ocean, India has demonstrated its desire and capability to be the first responder in the region. Its new bases such as the INS Jatayu in the Lakshadweep islands, INS Kadamba near Karwar in the Western Indian Ocean as well as in Agalega island in Mauritius multiply India’s operational reach and act as a force multiplier for power projection in the IOR.

In addition, to bolster defense cooperation with countries in the region, India has begun posting its defense attachés in several Asian and African nations for the first time, including the Philippines, Mozambique, Djibouti and Tanzania in early 2024.

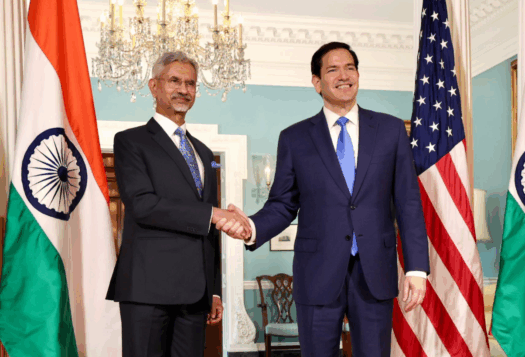

At the same time, New Delhi has realized that maritime threats are transnational and therefore require a joint effort. Therefore, naval ship deployment and port visits to like-minded regional countries have been a constant feature in recent years, extending to Fiji on the eastern side and South America on the Western side. Enhanced focus on the multilateral format of naval exercises such as MILAN, MALABAR, and ASEAN India naval exercises, the bilateral format, as well as coordinated patrols and passage exercises have only intensified in their scope and frequency in recent years. Additionally, the United States, France, Australia, the United Kingdom and other partners have been partnering with India to increase maritime domain awareness and information-sharing in the Indo-Pacific region for upholding international law and a rules-based order. Increasing international engagements of the Gurugram-based Information Fusion Centre- Indian Ocean Region, and the Quad Indo Pacific Maritime Domain Awareness (IPMDA) Initiative are aimed at “providing near-real-time, integrated and cost effective maritime data” to like-minded regional partners.

A relatively recent feature of Indian engagement with the region is providing defense supplies and equipment to help countries in the region stand up to China. Since 2020, India has gifted capacity-building platforms to regional nations such as Maldives, Seychelles, Vietnam, and Myanmar. The Philippines’ purchase of India’s indigenously-built Brahmos supersonic cruise missile in 2022 and interest shown by other countries such as Indonesia, Vietnam and Malaysia demonstrates a sign of trust in the country’s “Atmanirbhar Bharat” (self-reliant India) home-grown defense production program. On a strategic level, New Delhi has supported the Philippines’ sovereignty in the South China Sea and the two countries have a growing economic and defense partnership. In addition, to bolster defense cooperation with countries in the region, India has begun posting its defense attachés in several Asian and African nations for the first time, including the Philippines, Mozambique, Djibouti and Tanzania in early 2024.

Contestation in the Future

Sino-India tensions are no longer solely a territorial issue but have become part of a much larger regional issue, with China vying to be the dominant power in the region and rejecting the idea of a multipolar Asia. Therefore, the maritime domain of the Indian Ocean Region has become another theater of competition between New Delhi and Beijing, with potentially destabilizing effects. For one, China’s increased naval presence and deployments in the Indian Ocean create more opportunities for faceoffs with India at sea. Second, unlike China, India’s vision of the Indian Ocean complements that of most of the regional countries, i.e. to establish a rules-based maritime order with freedom of navigation, secure trade lines, open access to all, and mutual resolution of disputes. India’s active role in several dialogue initiatives such as the Indian Ocean Rim Association, Indian Ocean Naval Symposium, and the Quad is seen as a positive in resolving regional issues through dialogue and multilateralism. However, China has displayed repeated disregard for international law in the South China Sea in recent times, a behavior which could spill over into the Indian Ocean. New Delhi and others in the region would thus do well to prepare for a more fraught maritime environment in the future.

Also Read: Lakshadweep and Agalega: Implications of India’s Naval Dominance

***

Image 1: SpokespersonNavy via X.

Image 2: Indian and U.S. Navies via Flickr.