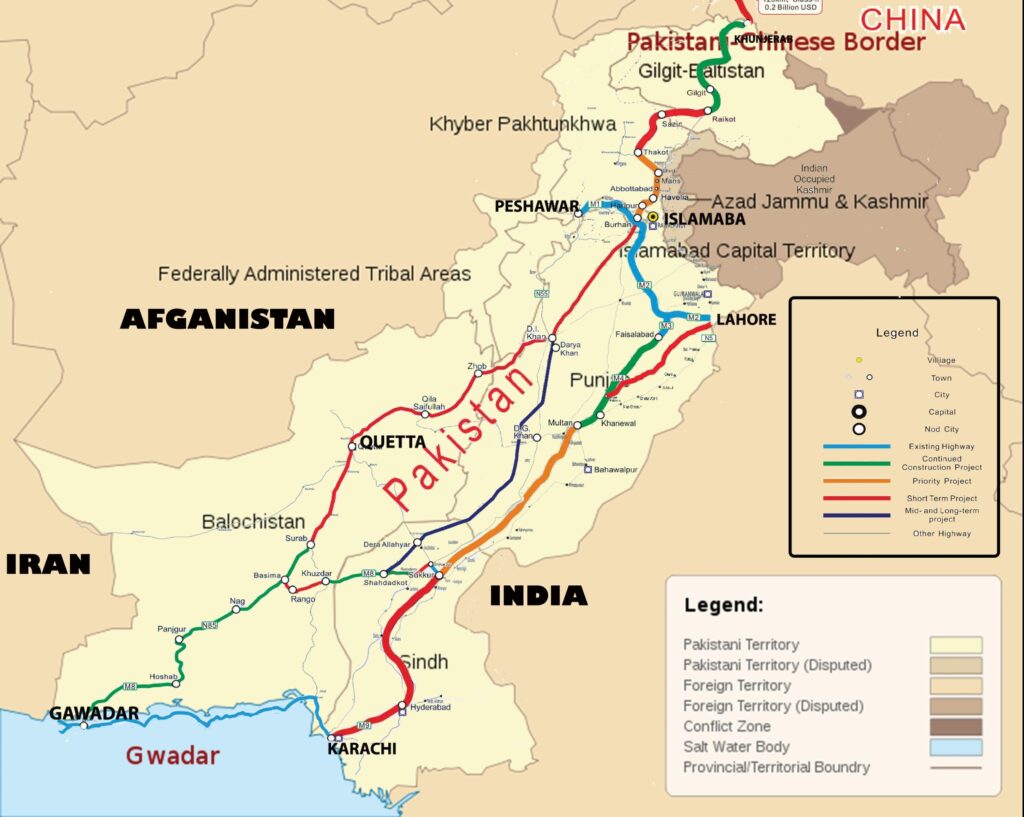

Formally launched in 2013, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) marked the flagship project of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. China has promised investments through CPEC totaling $62 billion. While both China and Pakistan call CPEC a win-win initiative, providing much-needed infrastructure to Pakistan and shortening trade routes for China with direct access to the Indian Ocean through Gwadar port, developments over the past decade tell a different story. Now, a decade after CPEC was first launched, the initiative has landed in uncharted territory, delivering very little and attracting myriad controversies. Not only have Pakistan’s development projects stalled over the past decade, but CPEC has also exacerbated longstanding tensions in Pakistan’s Balochistan province.

Persisting Challenges

Since its launch, CPEC has faced multiple challenges. The initiative is divided into three phases. The short-term phase (2015-2022), the medium-term phase (2021-2025), and the long-term phase (2026-2030). The first phase of CPEC focused on infrastructure, energy, and port development projects. However, corruption in Pakistan hampered smooth progress. The second phase of CPEC aims to establish 33 special economic zones (SZEs) with nine zones to begin with. The projects in this phase have also seen delays. Pakistan’s political instability, financial crisis, and terrorism have all limited the implementation of CPEC projects over the past ten years. These challenges persist to this day, worsened by current political and economic instability and the resurgence of terrorism following the US troop withdrawal from Afghanistan. While the third phase has yet to commence formally, the first two phases are unlikely to reach completion with the prevailing situation in the country.

A decade after CPEC was first launched, the initiative has landed in uncharted territory, delivering very little and attracting myriad controversies.

The slow progression of CPEC projects has also irked Beijing. The Chinese ambassador to Pakistan complained that Pakistan has destroyed CPEC. Even some in Pakistan have expressed concerns over the slow pace of work done on CPEC. Many projects have stalled, including the Main Line 1 railway project. This is the costliest component of CPEC, costing USD $6.8 billion. For this, the Chinese were to roll out USD $6 billion. However, misunderstandings between the two sides have led to delays in the project’s start date.

Lingering Controversies Around CPEC

Controversies have engulfed CPEC since it began. From the start, many in Pakistan worried that CPEC was a neo-colonial project that would give China control over Pakistan, like the British East India Company through which the British colonized the Indian Subcontinent. Others have conjectured that China would leverage its debt to turn Pakistan into a client state. Pakistan’s current economic crisis has fanned fears of this theory becoming a reality. In June 2013, Chinese loans to Pakistan were about USD $4 billion. This figure surged to more than USD $7 billion in 2017 and has been increasing ever since. At present China holds USD $30 billion of Pakistan’s USD $126 billion external foreign debt. Moreover, the IMF has also cautioned that increased Chinese involvement in Pakistan’s economy could bring both benefits and risks.

Pakistanis have criticized CPEC for benefiting China more than Pakistan. For instance, the Gwadar Haq Do Tehreek protested the differential treatment of the people of Gwadar despite being at the center of CPEC and asked the provincial government to provide the residents of Gwadar access to electricity and education, remove the check posts, and take action against the Chinese trawler mafia. The protestors threatened to block CPEC projects if their demands were not met. While the month-long sit-in ended when the provincial government promised to meet the Gwadar Haq Do Tehreek’s demands, the demands have not yet been met. Recently, the leader of the movement threatened that he would once again launch protests if the provincial government did not implement the agreement.

Besides this, Pakistani political figures have used CPEC for political purposes and continue to do so. For instance, the outgoing Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif recently accused the former PM Imran Khan of halting progress on CPEC and damaging relations with China. With Pakistan’s elections approaching, further politicization of CEPC is all but guaranteed.

Fueling Unrest in Balochistan

While CPEC promised to develop Gwadar and eventually Balochistan, it has engendered unrest in the province. The Baloch have demanded a greater share from the federal government in CPEC projects implemented in the province. Many times, Beijing and Islamabad signed agreements for CPEC projects in Balochistan without due consideration of the provincial government. As a result, the people of Balochistan are resisting CPEC, believing the projects would snatch away their freedoms. For instance, when Pakistan tried to fence Gwadar, lawyers from the province came out in protest against the fencing project, calling it a conspiracy against the people and the province.

From the start, many in Pakistan worried that CPEC was a neo-colonial project that would give China control over Pakistan, similar to the British East India Company through which the British colonized the Indian Subcontinent.

CPEC has also exacerbated existing fault lines in society, leading to an increase in violence. Insecurity in Balochistan has grown to such a level that the Chinese and their installments have become the target of frequent attacks by Baloch separatist outfits. For example, in 2018 terrorists from the Baloch Liberation Army attacked a Chinese consulate in Karachi, which was luckily foiled by the police. Likewise, four terrorists from the banned Baloch Liberation Army stormed the Pakistan Stock Exchange in 2020 where the Chinese have major investments. Moreover, in 2022 a suicide bomb blast by a female suicide bomber, Shari Baloch alias Bramsh, outside Karachi University, was aimed at Chinese nationals. In this suicide blast, three Chinese nationals were killed. In yet another incident this year, the Baloch Liberation Army set 6 Chinese mobile towers on fire. These incidents and their frequency show the extent to which CPEC has fomented insurgency in Balochistan.

Long Road to Actual Development

While CPEC promised to create 2.3 million jobs in Pakistan by 2030, by the end of 2022 it only managed to create 236,000 jobs out of which only 155,000 went to Pakistani workers. Out of the nine approved SZEs, four are still under construction and five are yet to be launched. The Pak-China Friendship Hospital, which was meant to create a state-of-the-art medical facility in Gwadar, was set to be completed by December 2022. However, it has not been completed yet and is projected to be completed by October 2023. Moreover, in the energy sector, the 884MW Suki Kinari Hydropower Project was to be made operational by 2022. Unfortunately, the project is still only 70 percent complete. There are six other energy-related projects under construction, with no certain dates of completion. Of the transport infrastructure projects, only six are completed, five are under construction, and thirteen are yet to start. While these are some of the major projects that are long overdue, CPEC has faced numerous other disappointments.

Conclusion

While CPEC has benefitted Pakistan in infrastructure and the energy sector in the short term, the long-term consequences of Chinese involvement in Pakistan will be detrimental for Pakistan, such as the potential loss of sovereignty. On the other hand, serious challenges to CPEC persist, such as the lack of institutional capacity, economic and political turmoil, and insecurity, which could slow down the work on CPEC almost to a halt for the next ten years. These hindrances could severely strain the Sino-Pak relationship, bringing the notion of all-weather friendship to the ground.

Also Read: Beyond BRI Connectivity: Chinese Access to the Indian Ocean Through Afghanistan and Pakistan

***

Image 1: CPEC Kas-Pul Bridge Battagram via Wikimedia Commons

Image 2: China-Pakistan Economic Corridor via Wikimedia Commons