Introduction

Sri Lanka’s widely-discussed economic crisis, which resulted from a combination of policy missteps, culminated in the country’s default on its foreign debt repayments in April 2022.

In response, Sri Lanka embarked on its 17th Extended Fund Facility (EFF) with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), attracting increased attention regarding the role of both multilateral and bilateral creditors in shaping Sri Lanka’s domestic economic policies.

Over the last two decades, Sri Lanka’s foreign credit landscape has undergone significant changes, with China’s increasing presence being a prominent feature. Sri Lanka has also maintained a long-standing relationship with the IMF, demonstrated by its participation in seventeen extended fund facility programs that have necessitated the implementation of specific economic policies aimed at achieving macroeconomic stability. This article examines how the rise of China has challenged the role of the IMF in shaping Sri Lanka’s economic policies and demonstrates how great power competition affects domestic policies in the political economy of the island nation.

Crucial reforms in taxation, the reduction of state expenditure, external debt management, and restructuring of state-owned enterprises are highly politicized.

The IMF’s Role in Sri Lanka’s Economic Policies

Since Sri Lanka gained independence in 1948, the IMF has played a significant role in shaping its economic policies. Sri Lanka has participated in a total of 17 IMF programs, including ten standby agreements, one structural adjustment facilitation commitment, and six Extended Fund Facilities (see Table 1). Historically, IMF programs have followed the Washington Consensus approach and critics argue that they impose strict fiscal commitments without regard for a country’s unique political and economic circumstances. However, proponents of the IMF argue that these programs have a positive impact on mobilizing capital from private lenders, despite the potential long-term risks posed by inadequate debt management capabilities of debtor countries.

Table 1: List of IMF’s historical commitments to Sri Lanka

| Facility | Date Announced |

| Extended Fund Facility | Mar 20, 2023 |

| Extended Fund Facility | Jun 03, 2016 |

| Standby Arrangement | Jul 24, 2009 |

| Extended Fund Facility | Apr 18, 2003 |

| Extended Credit Facility | Apr 18, 2003 |

| Standby Arrangement | Apr 20, 2001 |

| Extended Credit Facility | Sep 13, 1991 |

| Structural Adjustment Facility Commitment | Mar 09, 1988 |

| Standby Arrangement | Sep 14, 1983 |

| Extended Fund Facility | Jan 01, 1979 |

| Standby Arrangement | Dec 02, 1977 |

| Standby Arrangement | Apr 30, 1974 |

| Standby Arrangement | Mar 18, 1971 |

| Standby Arrangement | Aug 12, 1969 |

| Standby Arrangement | May 06, 1968 |

| Standby Arrangement | Jun 15, 1966 |

| Standby Arrangement | Jun 15, 1965 |

In Sri Lanka, the implementation of IMF programs has been contentious. Crucial reforms in taxation, the reduction of state expenditure, external debt management, and restructuring of state-owned enterprises are highly politicized. In the past, as in in other democracies with weak institutional frameworks, Sri Lankan politicians have prioritized short term gains to protect their own interests rather than focusing on prioritizing the implementation of unpopular but necessary economic reforms.

The changing dynamics in Sri Lanka’s foreign credit landscape

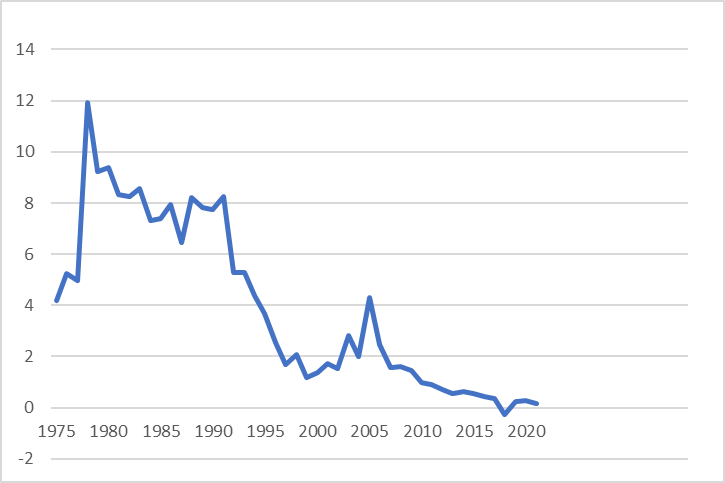

Sri Lanka’s internal development strategy to date has resulted in a twin deficit economy characterized by both a current account deficit and a budget deficit. While the country relied upon a combination of grants, concessional institutional borrowing, and import compression to keep deficits within an acceptable limit, the economic liberalization reforms of the late 1970s, together with an increased focus on infrastructure development led to an accumulation of external debt to cover the current account and budget deficits.

Sri Lanka’s economic assistance landscape has historically been dominated by multilateral organizations like the IMF and World Bank, but the country’s foreign credit landscape has undergone a significant change in the past two decades. In January 2010, Sri Lanka graduated from a lower income country to a lower-middle-income country on the World Bank classification system, restricting the country’s access to multilateral development finance. In light of its persistent twin deficits, the country reconsidered its budgetary financing strategy, prompting the government to explore funding options from the International Sovereign Bond Market (ISBs), due to the abundance of liquidity and lower interest rates. In addition, Sri Lanka relied on bilateral financing from major allies, particularly China, whose more accessible credit became increasingly palatable compared to the strict conditionalities of loans and grants from multilateral agencies such as the IMF.

Figure 1: Overseas Development Assistance as a percentage of GDP (1975-2020)

China’s Growing Influence in Sri Lanka’s Political Economy

During the final phase of Sri Lanka’s war against the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) from 2006 to 2009, the Mahinda Rajapaksa administration faced mounting international opposition against the war on human rights concerns. At this time, China emerged as the primary political and economic ally of the Sri Lankan government and gained significant ground in Sri Lanka’s foreign policy apparatus. Despite India’s deep social and cultural ties with Sri Lanka, the Indian government was hesitant to provide extensive military support due to domestic political concerns, particularly with the significant Tamil populations in Tamil Nadu. After Sri Lanka’s victory against the LTTE, China’s position in Sri Lanka was strengthened, leading to a pro-China stance in Sri Lanka’s economic policy during the subsequent Rajapaksa administration.

Since then, China has exponentially expanded its presence in the Sri Lankan economy by becoming a significant provider of development finance to the country. According to the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, China has invested approximately USD $2.2 Billion, becoming Sri Lanka’s largest foreign direct investor. China also holds almost 20 percent of Sri Lanka’s total external debt portfolio, making it the country’s number one bilateral creditor.

Chinese Debt and Sri Lanka’s Economic Growth Imbalance

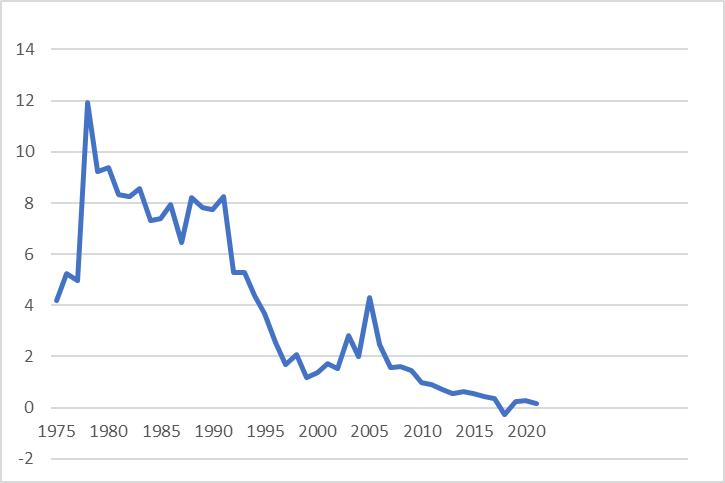

During the Rajapaksa administration, Sri Lanka’s tilt towards China raised concerns about the country’s relationship with its traditional lenders the IMF and World Bank. The peace dividend from the conclusion of the conflict with LTTE resulted in strong economic growth rates, while much-needed infrastructure development masked the imbalance in economic growth towards non-tradeable sectors. Non-tradable production contributed over 70 percent to the GDP increase between 2009 and 2021, while manufacturing’s contribution to GDP declined from 20 percent in 2005 to 17 percent by the end of 2019. This shift towards non-tradable production put increased pressure on Sri Lanka’s current account.

Figure 2: Current Account Balance as a Percentage of GDP (1975-2020)

Source : World Bank Data

The Western bloc has become increasingly anxious about Sri Lanka’s increased foreign debt portfolio and its preference for China in financing large infrastructure projects. Many analysts in the United States and Europe portray this economic relationship as “debt trap diplomacy,” suggesting that China provides loans for low-return projects and takes ownership of strategic assets when countries are unable to repay their debt. While the United States viewed the closer China-Sri Lanka relationship as a challenge to its own economic and strategic interests in the region, Sri Lanka’s traditional “big brother,” India, saw China’s growing presence as a potential threat. Sri Lanka now finds itself in a delicate geoeconomic scenario, navigating economic challenges while still seeking to maximize returns from China, the United States, and India alike.

Sri Lanka’s Balancing Act amidst Geo-Economic Concerns

Many analysts perceived the Rajapaksa administration’s growing authoritarianism as following the Chinese model, emphasizing state-driven economic growth while suppressing opposition. As the presidential elections approached, the opposition consequently called for reducing China’s influence. After the Rajapaksa’s defeat in 2015, the new Sirisena-Wickramasinghe administration attempted to improve relations with India and the Western bloc. The administration even suspended the China-backed Colombo Port City project, citing environmental concerns.

Responding to growing concerns about Sri Lanka’s mounting debt portfolio, the Sirisena-Wickramasinghe administration opted to negotiate a new EFF with the IMF. This enabled the government to refinance existing debt with new debt at lower interest rates in the short term, primarily through increased borrowing from ISBs. Economic growth, however, remained sluggish and a series of bomb blasts on Easter Sunday further undermined public confidence. The opposition gained momentum, eventually resulting in Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s election to the presidency on a populistic platform, promising to lower taxes and reinstate economic growth.

Sri Lanka now finds itself in a delicate geoeconomic scenario, navigating economic challenges while still seeking to maximize returns from China, the United States, and India alike.

What’s next for Sri Lanka?

When the Sri Lankan government changed hands in November 2020, the state’s ability to pay its debt had deteriorated to an unforeseen level, due to a combination of policy blunders and the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. The unprecedented crisis resulted in a wave of public protests against the Gotabaya Rajapaksa administration, leading to the formation of a new government headed by Ranil Wickramasinghe. The country has now negotiated a new agreement with the IMF, with strict conditionalities in revenue maximization and expenditure minimization, including reforms in State owned enterprises. In addition, the country is currently engaged in debt restructuring negotiations with the Paris Club, as well as conducting separate negotiations with other bilateral creditors such as China and India.

Sri Lanka’s past experiences with the IMF highlight the risks associated with the program, taking into account the political economy. Successfully implementing these reforms, along with the restructuring of past debt, would grant Sri Lanka access to funding from other multilateral agencies, including the World Bank, and enable the country to borrow from both bilateral and multilateral creditors again. However, implementing these reforms requires both political will and capital, both of which may be in short supply.

The Wickramasinghe government, then, faces the formidable challenge of actively balancing domestic political economy expectations with sound economic policies while simultaneously navigating competing geopolitical agendas to achieve improved economic outcomes for the country. This uphill task carries significant consequences, as a failure to accomplish this could potentially plunge Sri Lanka deeper into an economic abyss.

Also Read: The Real Cause of Sri Lanka’s Debt Trap

***

Image 1: Anti-government protests in Sri Lanka via Wikimedia Commons

Table 1: International Monetary Fund

Figure 1: World Bank Data

Figure 2: World Bank Data