In February, India’s Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced the new Vibrant Villages program in the Union Budget for FY 2022-23. The policy aims to re-populate and reverse migration from border villages in Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, and Arunachal Pradesh through improved infrastructure, access to energy resources and educational channels, and diverse livelihood opportunities.

While the Vibrant Villages program builds on India’s previous attempts to develop the border areas, the new policy—and the states it targets—reflects the government’s broader strategic concerns about the ongoing border standoff between India and China. Increasing emphasis on security is likely to overshadow the socio-economic dimensions of the initiative that focus on improving livelihoods, infrastructure development, and promoting access to education, which are also imperative to the program’s progress. Simultaneous developments on both the security and socio-economic fronts will be key to achieving all the program’s objectives.

India’s Border Management Strategy

The Vibrant Villages program builds on India’s previous border management strategies that have disproportionately focused on border security. For instance, in the Seventh Five-Year Plan (1985-1990), the government introduced the Border Area Development Program (BADP) to develop border infrastructure for the security of 457 blocks, 117 border districts in 16 states, and 2 Union Territories. Despite revisions in BADP to account for factors such as health, education, and agriculture, the program faced challenges due to the lack of a socioeconomic focus initially. Decreasing habitation, lack of connectivity, the scarcity of resources, and other issues, particularly in India’s northeast region, continue to constitute the main concerns of India’s border communities.

Increasing emphasis on security is likely to overshadow the socio-economic dimensions of the initiative that focus on improving livelihoods, infrastructure development, and promoting access to education, which are also imperative to the program’s progress.

Later, in the aftermath of the Kargil War (1999), the Government of India appointed a Kargil Review Committee (KRC) to comprehensively assess the borders and problems in national security. An outcome of this was the government’s recognition that safeguarding security at border areas would require measures beyond the conventional armed-security approach, including improving border infrastructure. As a result, several initiatives were implemented, including creating the Department of Border Management (2004), the Land Ports Authority of India (2012), and building Integrated Check Posts along India’s border to cross-border movement of trade and passengers. These initiatives emphasized on increasing connectivity rather than making the borders hard. The latter, however, is limited in coverage, focused mainly on major land trade routes, does not consider infrastructure development in other border areas, and remains security-oriented. Since the KRC, two more committees have focused on border security, but their findings have yet to be made public.

A Strategic Response to China?

The Vibrant Villages program’s announcement comes at the heels of China’s renewed push for border security on its side. On January 1, 2022, China enacted a new border law focused on safeguarding its national sovereignty through developing towns along its borders with India, Nepal, and Bhutan, and increasing the role of local residents in surveillance. Earlier in December 2021, China had also issued names for 15 states located in the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, which China calls “South Tibet.” Reports had also surfaced about China constructing a second “model village” or “Xiaokang” along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in Arunachal Pradesh. This is reportedly one of the 628 model villages that China has built along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) with India for approximately 30 billion Yuan (approximately USD $4.5 billion). China’s model villages have a dual-use purpose—as a residential complex to exert sovereignty and to act as a military cantonment. While India has not released details about the Vibrant Villages program yet, its geographical coverage focuses on the villages along India’s border with China in Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, and Arunachal Pradesh, forming a timely response to China’s developments along its own border.

The Way Forward: The Socio-Economic Dimension

While the government has still not released the details of the Vibrant Villages program, there are several factors that they must recognize while designing an implementation plan.

The government should clearly define the program’s objectives to ensure no duplication or overlap with India’s other border management programs, especially the BADP. The last few years have seen a decline in the budget for BADP, from Rs 1,100 crore (approx. USD $140 million) in 2017-18 to Rs 565 crore (approx. USD $70 million) in 2022-23. States have also decreased their utilization of funds, only spending nine percent in 2020-21, due to logistical challenges in implementing these programs and the COVID-19 pandemic. These challenges should inform the concept and implementation of the Vibrant Villages program.

The program should also create a task force or empowered committee to look holistically at the requirements for developing border villages and recruit officials from the security establishment (BSF, police force), administrative level (both at the Union and State Levels), and the Ministry of External Affairs to join. The task force or committee should also have representation from local administrations to respond to the unique needs of each village and ensure progress in its implementation.

At the local level, the program can create sustainable employment opportunities in border states by promoting agriculture and horticulture and creating border tourism opportunities. Furthermore, the government should aid these border villages with capacity-building by increasing funds to strengthen local village administrations and helping them to manage the various facilities that come with the program.

While India has not released details about the Vibrant Villages program yet, its geographical coverage focuses on the villages along India’s border with China in Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, and Arunachal Pradesh, forming a timely response to China’s developments along its own border.

Infrastructure development must focus on strengthening both forward and backward linkages. Road and highway development must focus equally on developing potential cross-border economic relationships as on the engagement with the nearest Indian towns. The increase in the budget estimates for Border Roads Organization (from Rs. 2,500 crores or approx. USD $325 million to Rs. 3,500 crores or approx. USD $460 million) in the Union Budget indicates that the government is already making good progress on this. Furthermore, the border villages must have better connections with mobile and internet facilities with lower downtime. Setting up mobile towers and radio networks and speeding up the laying of optical fibers in the border areas should be a policy priority.

Finally, the government must increase the stake of local villages in the program’s border projects. If the economic dividends are high, the border villages are more likely to stay inhabited. The program should also include implementing a survey on the effective ways of making locals key stakeholders in major infrastructure projects, such as ensuring a guaranteed share of employment in local projects.

Conclusion

Border areas are crucial strategic zones, and the development and re-inhabitation of these spaces are one of the few ways to assert a claim over the land. The Vibrant Villages program is the latest initiative to manage India’s borders by adopting a holistic approach. While the program directly responds to the India-China border conflict, the socio-economic dimension must be given equal importance as the security dimension to ensure sustainable development of the villages. India must learn from previous similar schemes and prioritize the well-being of the populations in the villages targeted by the program.

***

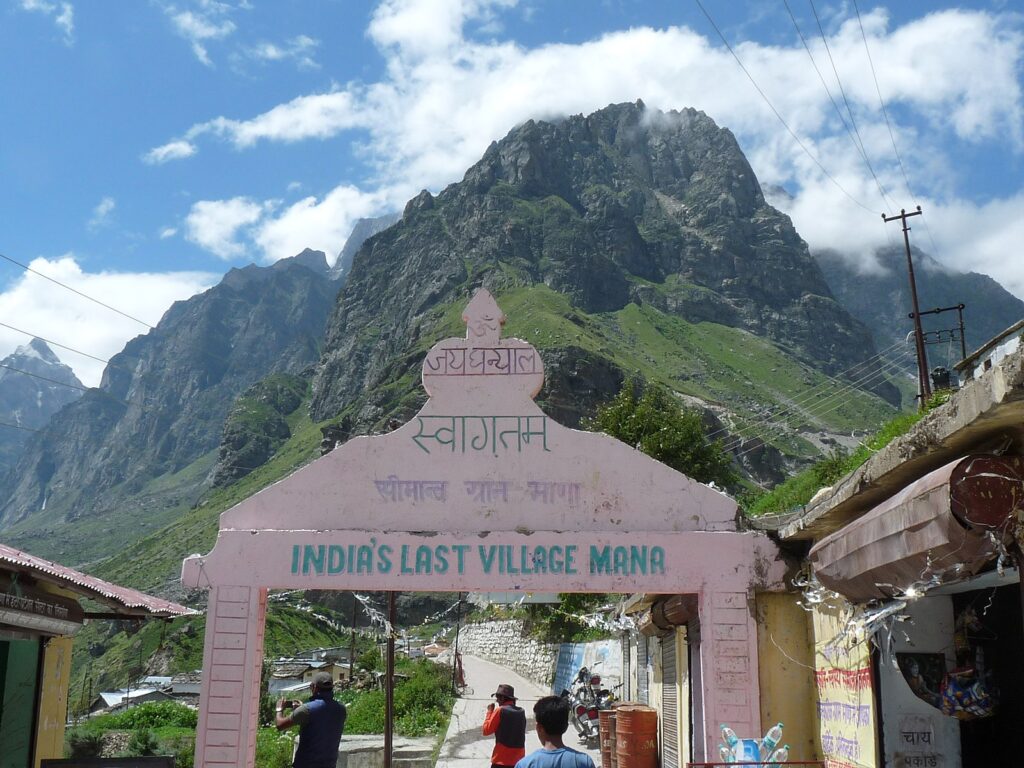

Image 1: Lakun Patra via Wikimedia Commons

Image 2: Wikimedia Commons