International actors—most recently the United States and its partners in NATO—have devoted significant resources to increasing stability and state capacity in Afghanistan over the past almost twenty years. Despite these efforts, the road to stability remains long and rife with challenges. The Afghan Taliban poses the most notable threat to peace and stability in Afghanistan. Closed-door talks between the United States and the Taliban began in September 2018 in Doha. On August 22 of this year, negotiators from both sides sat down for their ninth round of talks, having suggested they were nearing an initial peace deal for Afghanistan. However, President Trump called off the U.S.-Taliban talks last month. Had the negotiators agreed to a deal, it would have been the first step towards ending the United States’ longest war on foreign soil. In past rounds, both sides had agreed to a “draft framework” that incorporated the withdrawal of U.S. troops, the Taliban’s responsibility to prevent global terror groups from using Afghan soil, a ceasefire executed across the country, and continued intra-Afghan negotiations.

Before calling off the talks, President Trump had arranged a secret meeting with the Taliban leadership and separately with President Ashraf Ghani at Camp David. The discussions were intended to produce a consensus on the removal of U.S. troops from the country after nearly two decades of war. An agreement “in principle” would have required Washington to provide a timeline for pulling 5,400 U.S. troops out of five military bases in Afghanistan in the coming 135 days. In turn, the Taliban would have agreed to end its support for terrorist groups operating on Afghan soil. This anticipated deal would have made way for intra-Afghan talks between the Taliban and the Afghan government. Ultimately, however, the latest peace agreement did not lay out the sufficient terms for a prolonged peace. A hasty withdrawal of troops could lead to greater instability and Taliban violence in Afghanistan. Likewise, the agreement did not include any means of guaranteeing Taliban cooperation (it was an “in principle” agreement, rather than a “conditions-based” agreement). As the involved parties look towards future peace accord opportunities, it is important to acknowledge the fundamental flaws in this rejected agreement.

Cancelled U.S.-Taliban Talks: Violence Begets Violence?

The latest peace agreement did not lay out the sufficient terms for a prolonged peace. A hasty withdrawal of troops could lead to greater instability and Taliban violence in Afghanistan.

After the United States and the Taliban agreed “in principle” to a host of the issues on the table, some of the final details were made public. However, this agreement did not resolve some of the most pressing issues between the two sides. First, the draft agreement did not include any clauses guaranteeing Taliban follow-through on its commitments. It did not call for a complete ceasefire. Throughout the nine rounds of talks, the Taliban barely discussed the conditions they would abide by to sustain a peaceful settlement with their fellow Afghans. Taliban insurgent violence persisted and even increased amidst the peace talks, and especially as the discussions hit a roadblock.

Second, the deal detailed the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan, but did not specify whether U.S. counterterrorism forces would remain to fight al-Qaeda. The hurried withdrawal of troops could lead to a nasty civil war, which might engender the very conditions that had led to the emergence of the Taliban. In the midst of the swift withdrawal process by the Soviet Red Army in mid-1989, the Soviets prematurely handed power to certain provinces. The new governing authorities were ill-equipped to govern the country, contributing to the rise in power of Islamist insurgents and plunging Afghanistan into civil war. After a three-year civil war between the de-facto government and rival factions of the insurgent mujahedeen, the Taliban emerged victorious, attracting popular support by claiming to uphold peace and rule of law.

Avoiding a Repeat of History

The current situation in Afghanistan—in light of the cancelled talks—presents similar conditions as these historical ones and grants the Taliban significant leverage vis-à-vis the Afghan government. The Taliban does not recognize the current constitution. Throughout the talks, the Taliban negotiators refused to meet with the government in Kabul. The Taliban has no prior history of working alongside any political parties in Afghanistan and considers the Afghan government an illegitimate “puppet regime”. The fundamentalist group regards itself as Afghanistan’s legitimate government and refers to an Afghanistan under its control as the “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.” This could all generate mass violence and insurgency. At the same time, the Islamic State-Khorasan Province (ISKP) has expanded from its fortification in eastern Afghanistan, gaining traction in light of the cancelled peace talks. ISKP might capitalize on greater instability and a potential power vacuum to ramp up its recruitment efforts and international terror activity, potentially in collaboration with al-Qaeda. History seems ripe to repeat itself.

In the likely event of intra-Afghan discussions, the Taliban may take coercive measures to secure even greater leverage. After the Taliban was ousted in late 2001, they reorganized and re-surged, targeting the U.S.-backed government in Afghanistan. With Afghanistan currently in the middle of national elections, it would not be out of character for the radical group to attempt to usurp power from the Afghan government and establish its own rule. Indeed, senior Taliban leaders are reported to have begun reaching out to government officials offering them positions in a future, Taliban-led administration.

History seems ripe to repeat itself. In the likely event of intra-Afghan discussions, the Taliban may take coercive measures to secure even greater leverage.

These seeds were partially sown by the negotiation terms, which excluded the Afghan government from discussions. Since the onset of U.S.-Taliban talks in 2018, the Ghani administration has criticized the negotiations, believing they lacked transparency and sidelined the official Afghan government. Some Afghans actually welcomed the severing of talks. Ultimately, as the Taliban now attempts to seize an advantage in light of the cancelled talks and ongoing elections, the Afghan government’s absence represented the biggest roadblock to successful U.S.-Taliban talks. Any future peace talks would need to prioritize the needs and concerns of Afghans, which can only happen if Afghans are involved in the negotiations.

Conclusion

The United States’ haste to withdraw its troops from Afghanistan has caused Washington to sideline the Afghan government throughout its negotiations with the Taliban and led to a draft deal that did not force the Taliban to abide by its stated criteria. Any credible peace deal in the future must bind the Taliban to commence talks with the Afghan government, demobilize its insurgency, and cut ties with international terrorist groups. With or without a deal, the international community’s effort must focus on legitimizing the Afghan state by including it fully in the peace process, building solidarity towards a more peaceful and capable Afghanistan.

***

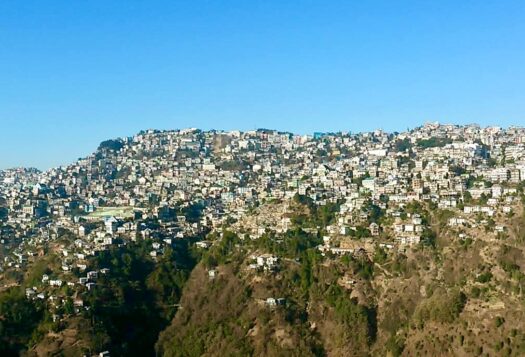

Image 1: Wikimedia Commons

Image 2: Paula Bronstein via Getty Images