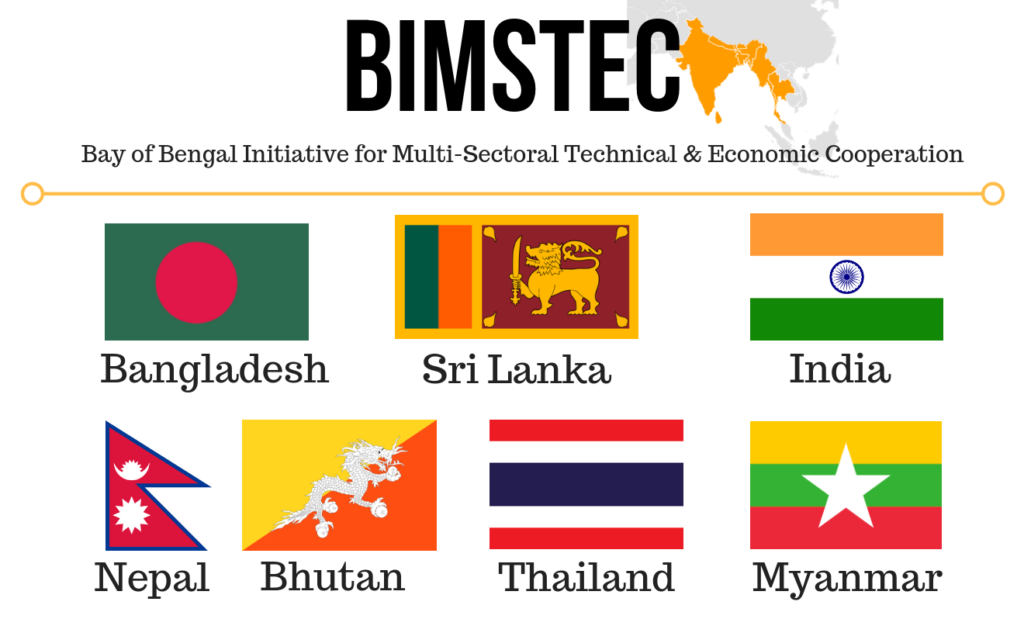

The recently re-elected Narendra Modi-led government in India is poised to continue its “neighborhood first” policy in its second term. However, there has been a change in how India understands and delineates its neighborhood, a stance which is explicit in the shift in New Delhi’s focus from the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) to the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC). The first visible move was Modi’s invitation to BIMSTEC leaders to attend his swearing-in ceremony last month while on the same occasion in 2014, Modi had invited SAARC members. This indicates how BISMTEC is being highlighted as India’s preferred regional grouping, an idea that was given more credence by External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar recently, who commented that India sees BIMSTEC as having new energy and possibilities, unlike SAARC that has its own problems.

India’s shift from SAARC to BIMSTEC can be assessed as a combination of two broad factors. First, SAARC has been internally fraught, with the Indo-Pak rivalry at the heart of the organization proving to be a paralyzing deadlock. For New Delhi, the hopes of an India-led model of regionalism will never be possible with Pakistan in the same grouping. Thus, the logic of convenience dictates that SAARC minus Pakistan is the road ahead if India wants to be a regional leader in its neighborhood. However, South Asia is incomplete without Pakistan and Afghanistan. Thus, the second factor driving India’s shift from SAARC to BIMSTEC is imagining its neighborhood not from a continental, South Asian frame of reference but a maritime one, which is a corollary to its advances in the east over the years.

A Defunct SAARC

One of the major reasons for India’s shift away from SAARC has been the moribund nature of the organization, owing to conflict between India and Pakistan. Called a “slow boat to nowhere” by Indian strategic analyst C. Raja Mohan long ago, SAARC has been unable to solve a major puzzle since its inception—how to be a functional organization that is able to produce successful outcomes without being impacted by the fundamental differences between India and Pakistan. Over the decades, the deadlock has only worsened, and the summits have been reduced to diplomatic niceties.

India’s shift from SAARC to BIMSTEC can be assessed as a combination of two broad factors. First, SAARC has been internally fraught, with the Indo-Pak rivalry at the heart of the organization proving to be a paralyzing deadlock. […] The second factor…is imagining its neighborhood not from a continental, South Asian frame of reference but a maritime one.

The most contentious issue in recent years has been cross-border terrorism, which also led to the cancellation of the 2016 SAARC Summit in Islamabad. The primary cause of this deadlock was one of the deadliest attacks on the Indian Army in Kashmir in recent years, at a military installation in Uri in Indian-administered Kashmir, which India believes was carried out by Pakistan-based terrorist outfit Jaish-e-Mohammed. In the wake of the Uri attack, India decided to boycott the SAARC summit in Islamabad and diplomatically isolate Pakistan. Following India’s lead, Afghanistan, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Maldives, and Sri Lanka also walked out of the summit. In the last functioning summit till date in Kathmandu in 2014, Pakistan had blocked most India-led proposals related to South Asian connectivity while also staying away from the South Asian satellite project mooted by New Delhi, eventually launched in 2017. The doomed nature of SAARC is rooted in the India-Pakistan rivalry and the revival of the grouping should not be seen in terms of summits but functionality and deliverables. With territorial disputes, the presence of nuclear weapons, and innate mistrust between India and Pakistan, SAARC is likely to continue to suffer from ineffective implementation unless the nature of the relationship between the South Asian rivals changes.

A New Cartography for Regionalism

While India is curtailed on the west due to Pakistan, it has solidified its relations to the east, particularly with the ASEAN states, through its Look East and now Act East policies. Focusing on BIMSTEC gives India three opportunities. First, centered primarily on the Bay of Bengal, BIMSTEC has the capacity to connect South and Southeast Asia through the sea, becoming a medium of trade and connectivity. This sea connectivity to Southeast Asia gives India exposure to the important shipping lanes linking the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, with a chance to develop trade links with the burgeoning economies of Southeast and East Asia. It also expands India’s traditional arc of influence, which currently stretches from the Strait of Hormuz on the west to the Strait of Malacca on the east.

Second, moving away from a rigid mental map of its neighborhood gives India a chance to create new, fluid identities, particularly maritime-centric ones. Renewing its link with the ocean and re-traversing its age-old connectivity to Southeast Asia is more a case of rediscovery rather than creation for India–adopting this new ontology gives New Delhi the chance to capitalize on the gains it has made in Southeast Asia and East Asia in recent years.

Third, India’s sea drift is also a necessity owing to the realities of the region. China is seeking to expand its capabilities and influence in the IOR, by developing ties with Myanmar, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives, among others. Thus, having deeper ties with the littoral states and a supportive and cooperative neighborhood as well as offering greater commitments to the region in terms of being a net-security provider would help India counter the advances that China has been making. In this connection, Prime Minister Modi’s first foreign visit in his second tenure to two Indian Ocean states where China has had a considerable footprint in the recent past – the Maldives and Sri Lanka – is instructive.

Recognizing the Constraints

BIMSTEC should have a rationale of its own along with a clear vision and actionable goals that appeal to all its members. Advancing BIMSTEC as a replacement of SAARC would only breed resistance, which could result in lack of political will on the part of member states with stakes in both groupings.

The constraints that India faces in terms of prioritizing BIMSTEC over SAARC are two-fold. First, India’s prioritization of BIMSTEC has often been seen by analysts as a “rebound relationship,” which only resurfaces every time there is talk of the need for a replacement for SAARC. The idea of BIMSTEC has generated skepticism even among leaders of member states, like Nepalese Prime Minister KP Oli and Sri Lankan President Maithripala Sirisena, who have said that the grouping should not replace SAARC. While SAARC’s incapacity is undoubtedly one of the reasons for BIMSTEC’s perceived rise, it is definitely not the only one. India needs to de-hyphenate the two models and present them as a zero-sum game to create a credible and more positive narrative for its shift. In simple terms, BIMSTEC should have a rationale of its own along with a clear vision and actionable goals that appeal to all its members. Advancing BIMSTEC as a replacement of SAARC would only breed resistance, which could result in lack of political will on the part of member states with stakes in both groupings.

The second constraint is more logistical and conceptual. BIMSTEC’s own record has been dismal in terms of concrete achievements. In over 20 years, it has only four summits to its name. Until 2014, it did not even have a secretariat and even at present, the secretariat is severely understaffed with a paltry budget. India has to overcome the tag of underperforming in this grouping and if it has to champion regionalism with this new cartography, it has to walk the talk on its commitments. A good start has been made by Jaishankar, who has emphasized greater cooperation in the context of BIMSTEC, projecting India as a benefactor in the region. Building goodwill by offering favorable terms of engagement to its neighbors in terms of trade and connectivity and following through on deliverables can help New Delhi project itself as an attractive and benign power in the region.

While the shift from SAARC to BIMSTEC is a shift of convenience and necessity, its success would depend on New Delhi’s political will and its ability to deliver on its promises to its neighbors.

***