It has been two years since the Hizbul Mujahideen (HM) commander Burhan Wani was killed in an encounter in Bumdoora village in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). His killing on July 8, 2016 led to mass civilian unrest and the deterioration of law and order in many districts across the Kashmir Valley, which resulted in the killings of many civilians and security personnel. Additionally, Wani’s death has changed the nature of the conflict in Kashmir, bringing about an upswing in local militancy along with an increase in general support for the Kashmiri cause.

Even two years after Wani’s death, the situation remains tense in the Valley, making for a challenging security environment complicated by an equally difficult political situation. J&K is now under Governor’s rule after the break-up of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-People’s Democratic Party (PDP) coalition government in June, but the state will see three crucial elections in the next year: Panchayat, State Assembly, and Lok Sabha. Holding these elections will be a difficult task for the BJP-ruled central government in the present security environment, but it is not unachievable. However, in order to hold and win elections, the BJP needs to regain the trust of Kashmiris. It can do so by going through with the dialogue process it has already initiated with separatists, ensuring that all of Kashmir’s various political stakeholders have a seat at the table.

Post-Burhan Wani: An Indigenizing Militancy

The Kashmir Valley has seen a decisive shift in local militancy since the Wani encounter: it is more indigenous now, as the number of local youth involved has increased from 88 in 2016 to 126 in 2017. According to recent figures dating to mid-July of this year, local youth recruitment in different militant outfits has surpassed 2017’s number and stands at 128 for the first seven months of 2018. Indeed, after the July 2016 civilian turmoil, the Kashmir issue has found increasingly more support among the general population, turning it into more of a domestic issue rather than one heavily influenced by outside actors. Geographically, this means that the innermost districts of the Valley–Pulwama, Shopian, Anantnag, and Kulgam–are presently the most militancy-affected areas, as opposed to the districts in the north, near Pakistan.

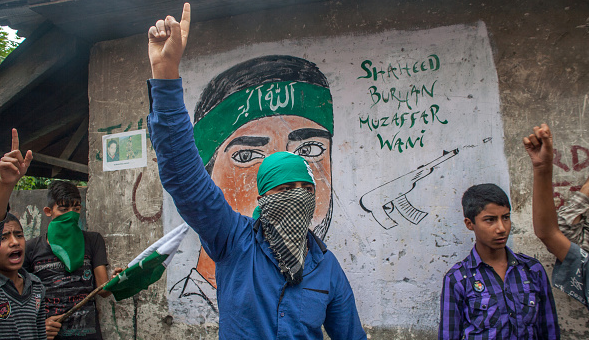

This phenomenon can be, in part, explained by the effect Burhan Wani’s death has had on Kashmiris, with Wani becoming a household name in some parts of Kashmir. Many young Kashmiri boys are willing to follow his footsteps and join a militant group to fight against the Indian state. This includes even well-educated individuals and former security forces personnel. For instance, Junaid Ashraf Khan, a graduate from the Kashmir University and son of the leader of the Tehreek-e-Hurriyat (Movement for Freedom), a separatist political party, joined HM in March this year. Moreover, unlike earlier uprisings, local militants are receiving significant support from the local civilian population. Glorified mass funerals of militants, civilians thronging encounter sites in large numbers, and incidents of stone pelting on security forces have become increasingly common phenomena since 2016.

Changing perceptions of local militancy have had an impact on how groups maneuver Kashmir’s saturated landscape of militant actors. In contrast to the 1990’s insurgency, Kashmiri youth who are joining militant outfits are not crossing over to Pakistan for arms training or seeking ideological motivation. These are mostly self-motivated and disillusioned boys volunteering to join militant ranks and to die for azadi (freedom). Besides snatching weapons from security forces, local militants are mostly indulging in smaller-scale attacks such as random firing at security personnel and the killing of informers, and rarely conduct fidayeen (suicide) attacks, unlike their professionally-trained counterparts from Pakistan.

Another footprint of the indigenizing nature of the militancy is that, according to reports, the overwhelmingly local Hizbul Mujahideen remains the first preference of the new recruits, followed by the Pakistan-influenced Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammad groups. New groups such as Al-Qaeda’s local branch Ansar Ghazwatul-Hind and Kashmir’s Islamic State branch have also propped up in the last two years. Notwithstanding their online presence, these groups have not been able to attract many people on ground given that many are still joining the aforementioned local separatist militant outfits. Nonetheless, the success of Indian security forces in eliminating top militant commanders, especially after the launch of the Operation “All Out” in 2017, has not done much to slow down the recruitment drive, which has continued unabated in the Kashmir Valley.

Navigating the Political Way Forward

The evolving nature of local militancy indicates that Wani’s death likely provided an outlet for the deep alienation and anger generated after the Valley-based PDP came into an alliance with the rival BJP in 2015 as well as the mismanagement of other domestic affairs in Kashmir. The resulting street violence and increase in support to militant groups after July 2016 led to the near absence of the local governance system, due to instances of violence against local politicians and political workers.

Despite this, there has been a slight improvement since the imposition of the governor’s rule after the break-up of the BJP-PDP alliance this June. There has been a dip in the militant-related violence in the Valley. Moreover, the focus is on providing good governance and addressing grievances of the civilian population in the state. The BJP-ruled federal government’s foremost priority is conducting delayed Panchayat elections and call for fresh state assembly polls in J&K. The outcome of these elections will pave the way for the 2019 Lok Sabha polls in the state. If law and order does not improve, then New Delhi might consider delaying these elections. Under no circumstances would the central government want to see the repeat of the 2017 Srinagar-Budgam by-election, which was mired in excessive violence and witnessed a turnout of just 6.5 per cent.

With the 2019 Lok Sabha elections are fast approaching, New Delhi might consider restarting the dialogue process with different stakeholders, including the All Parties Hurriyat Conference leadership. India’s Home Minister Rajnath Singh and the Center-appointed interlocutor, Dineshwar Sharma, have invited the separatists for a dialogue with an aim to ensure peace and stability in the Valley. Arguably, this indicates that the BJP government understands that “hard” security measures by themselves will not improve the present situation in Kashmir. In order to hold elections and form a democratically-elected state government in J&K, the central government will need to blend the use of security forces with engagement and dialogue with different political stakeholders. These include parties in the state, local economic bodies, representatives from educational institutions, and other stakeholders from all three regions of Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh.

At present, New Delhi’s main worry remains winning the trust of the disgruntled civilian population, which holds the power that comes with voting. The government needs to adopt a holistic approach in order to address local concerns in J&K before it is too late. The time is ripe for New Delhi to take a step forward in initiating the dialogue process with different stakeholders to regain confidence of the civilian population in Kashmir.

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

Image 1: Jesse Rapczak via Flickr

Image 2: Yawar Nazir via Getty