Though China has commanded significant attention from India’s strategic community, especially in the last two decades, it has dominated security and foreign policy thinking like never before since the start of the Doklam incident. Despite moments of conciliation, relations with China remain tense, a trend unlikely to reverse anytime soon. China’s hegemonic rise over the last three decades has supported sustained growth across Asia, but it has also placed unprecedented stress on the security order in the region and beyond.

China’s economic growth has also fuelled the transformation of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) into a modern fighting force capable of defeating major foreign powers. This development presents a long-term, multifaceted challenge to India with regard to its disputed border with China (the Line of Actual Control or LAC) and India’s maritime periphery. Differences over foreign policy, proactive land grabbing, and China’s military modernization have forced the Indian policy community to prepare for the possibility of a serious confrontation with China.

While there are no easy answers or simple formulae to counter China’s unipolar Asian order, it is vital to understand how its changing capabilities, doctrines, and tactics impact India’s deterrent.

Doklam: Latest Evidence of Deteriorating China-India Ties

While the history of the current Indo-Sino impasse can be traced back to the 1962 border war between the two countries, the recent Doklam standoff represents the first confrontation between the two Asian giants in this area of the Himalayas since the clashes at Nathu La and Cho La in 1967. The Doklam standoff was unique in that it revolved around territory disputed between China and Bhutan, not China and India. The Indo-Sino border in this sector had been bereft of any major incidents and relatively quiet since the alignment of the Sino-Indian border in Sikkim is broadly accepted by both sides. But it now seems that the location of the disputed China-India-Bhutan trijunction border will likely remain a source of contention in the years ahead.

The standoff at Doklam needs to be viewed as more than just a boundary incident involving India, China, and Bhutan. It is a harbinger of an Indo-Sino geopolitical clash. India’s refusal to be intimidated by China’s aggressive land grabbing becomes clear when situated in the context of bilateral ties over the last two years—China has consistently blocked India’s NSG membership, it has not allowed the blacklisting of Pakistan-based terrorist group Jaish-e-Muhammad’s chief Masood Azhar at the United Nations, and is developing the China-Pakistan Economic corridor, which goes through territory claimed by India. China has also tested Indian resolve by portraying it as an unreliable partner to its smaller neighbors in South Asia and debunking the idea of India as a net security provider.

China Makes Inroads in India’s Backyard

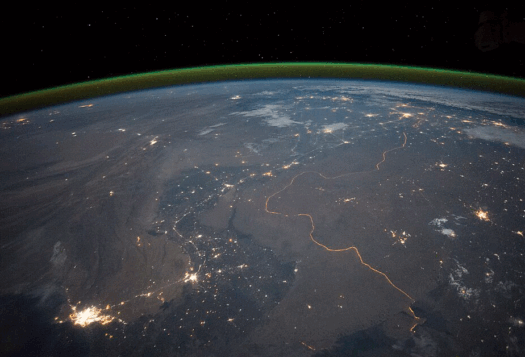

Beijing’s proactive courting of India’s neighbors and its moves in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) have increased India’s strategic anxieties. In addition to China’s development of the Gwadar port in Pakistan, the Hambantota port in Sri Lanka, the Kyaukphyu port in Myanmar, and strengthening trade and political relations with both Bangladesh and Nepal, China also recently constructed its first-ever military port in Djibouti giving significant strategic depth to its naval operations in the IOR, much to New Delhi’s chagrin.

Despite India’s access to a number of ports in the IOR such as Sittwe in Myanmar, the Seychelles, and Mauritius, the rate of Chinese expansion in the IOR places stress on India’s diplomacy in the region. Japan’s intervention to jointly develop the Chabahar port in Iran and in developing an Asia-Africa growth corridor underlines India’s capacity deficits in regions New Delhi views as strategically critical for market access and strategic posture vis-s-vis China.

China-Pakistan Cooperation: A Growing Concern

Despite these concerning trends among small South Asian countries, a key issue of concern in the Indo-Sino dyad is Pakistan’s strong ties with China. The China-Pakistan relationship has provided Islamabad a strategic cover for its asymmetric activities versus India. This relationship has also assumed strategic importance in the wake of India’s tilt towards the United States. New Delhi’s perceived two-front threat perception too becomes relevant here given that Chinese military support to Pakistan is incrementally reducing the conventional military gap between India and Pakistan. Pakistan currently accounts for approximately 35 percent of China’s defense exports, making it the largest recipient of Chinese equipment.

While there exists good reason for skepticism about the extent to which Beijing would overtly support Pakistan’s symmetrical or asymmetrical actions against India, there exist legitimate concerns about an opposing scenario in which Islamabad may support Beijing in an India-China conflict. Driving these concerns in Delhi are Beijing’s increasing economic footprint in Pakistan—in the form of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) that comes under the umbrella of the Belt and Road Initiative—which makes Pakistan an important stakeholder in a future India-China conflict. Given Pakistan’s volatile and politically unstable domestic security situation, the viability of Chinese investment remains suspect at best. The prevailing situation is, however, unlikely to reduce China’s economic footprint in Pakistan since CPEC developments are part of a grander Chinese agenda of regional economic connectivity.

To counter China in an increasingly contested maritime domain, India will need to develop the capability to deploy and operate out-of-area of its immediate vicinity. Key to building on that potential will be Indian access to certain military bases in the region — like Diego Garcia, Djibouti, Bahrain, and the Australian Coco (Keeling) and Christmas Islands. This will help India build on its aspiration of a “net security provider” in the region and expand its out-of-area humanitarian assistance and disaster relief capability as well as anti-submarine warfare operations. Agreements like the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement with the United States hold the potential to enable and extend Delhi’s writ deeper into the Indian Ocean vis-a-vis China. While mutual consent is a tenet of any such agreement, Indian access to certain foreign bases would be mutually reinforcing and is worth exploring given the potential to reduce the demands on the logistical front in an unpredictable strategic competition.

India’s China Strategy

As India takes a position in the liberal global order consummate with its growing aspirations, managing its relationship with China will be of utmost importance in New Delhi’s foreign policy calculus. Having called the bluff against Beijing’s aggressive land grabbing exercise along its periphery, India will now need to internalize and cement its position in the region as a geopolitical actor of consequence versus China. Maintaining this effectiveness in the medium and long-term in managing the disruptive rise of China needs to be located at three levels of activity: the strategic, the economic, and the military. While overlapping, each will play a decisive role in countering events that might occur along India’s periphery as the geostrategic fault lines in the Indo-Sino relationship become ever more evident.

Editor’s note: This is the final installment of South Asian Voices’ new six-part series, China in South Asia. In this series, our contributors Fatima Raza from Pakistan, Saimum Parvez from Bangladesh, Avasna Pandey from Nepal, Kithmina Hewage from Sri Lanka, Ahmad Shah Angar from Afghanistan, and Pushan Das from India explore China’s strategic and economic goals in their respective countries, the challenges China may face in implementing those goals, and how China’s engagement will affect the regional balance of power in South Asia. Read the entire series here.

***

Image 1: Narendra Modi via Flickr

Image 2: Umairadeeb via Flickr