As uncertainty regarding U.S. troop presence looms over Afghanistan’s peace and reconciliation process, observers are looking at the role of other important regional players in the negotiations. So far, China’s diplomatic influence has been instrumental in getting the Taliban to the negotiating table. This influence, however, is still reliant on Pakistan’s leverage over the Taliban and other militant groups. As threats to China’s own security from cross-border terrorism increase, it would be worthwhile to understand China’s limitations in ensuring stability in Afghanistan, to set expectations right.

China’s Erstwhile Approach in Afghanistan: Turning a Partial Blind Eye

China has a vested security interest in Afghan stability. Its objective has been to ensure that Uighur militants of Turkestan Islamic Party (TIP) or East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), militant groups that aim to create an Islamic state in Xinjiang, do not use Afghanistan as a training and logistics ground to perpetrate attacks against China. In the past, China has attempted to secure its interests by maintaining ties with two of the most influential players in Afghanistan following Soviet withdrawal – the Taliban and Pakistan. Since 2000, when China’s Ambassador to Pakistan, Lu Shulin met Mullah Omar, China has remained one of the few countries to maintain ties with the Quetta Shura, the Taliban’s leadership council in Pakistan. It comes as no surprise then that Maulana Samiul Haq, who is known as the “Father of the Taliban” and is reportedly close to the current Taliban leader Haibatullah Akhundzada, has called for a larger role for China in the Afghan peace and reconciliation process.

While Beijing has achieved limited success, its narrow approach of targeting a section of militants rather than their operating environment, as Andrew Small has argued, has proved insufficient in protecting itself against anti-China terrorists in the Af-Pak region. For instance, though the Taliban leadership assured Beijing that its territory would not be used by any militant groups for operations against China, the group did not stop Uighur militants from embedding themselves with other Central Asian groups that were anti-China, like the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU). In addition, China was able to get Pakistan and the United States to act against IMU and ETIM. But protracted conflicts, like the one in Afghanistan, often lead to splintering of the parent organization and the emergence of “fragmented oppositions,” who differ in their approach and partner with different groups in order to meet their original objective. This makes the conflict landscape in this region even more complex and has limited the ability of China’s ally Pakistan, with powerful proxy actors in the conflict, to act against all splinter groups of a specific militant organization.

Countering Anti-China Militants: Pakistan’s Dilemma

Tracing the history of Uzbek groups in the Af-Pak region helps elucidate the dangers of China’s over-reliance on Pakistan to stabilize the region and why Beijing may be looking for more partners to secure its interests in Afghanistan. Following the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, IMU along with the Taliban and al Qaeda shifted their bases to Pakistan. In 2007, Maulvi Nazeer, a militant leader with close ties to the Haqqani Network, a Pakistani proxy militant organization in Afghanistan, led an operation to flush out Uzbek militants from Pakistan’s South Waziristan that was supported by elements of the Pakistani state. This led IMU to align itself with Baitullah Mehsud’s Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan in North Waziristan, a militant organization that targets the Pakistani security forces, and attack the Pakistani state. Meanwhile, the Haqqani Network maintained a tactical alliance with IMU in Pakistan’s North Waziristan to facilitate select attacks in northern Afghanistan but in Afghanistan, it began embedding and conducting joint operations with the militants of the Islamic Jihad Union, an off-shoot of IMU.

Thus, the ties which Uzbek militants have cultivated with the Haqqani Network make it challenging for Pakistan to target the organization’s factions that support anti-China Uighur militants in the Af-Pak region. IMU’s survival allowed Uighur militants to proliferate between FATA in Pakistan and eastern and southern provinces of Afghanistan, and it is from here that they continue to threaten the Chinese state. Additionally, the Taliban has done little to stop al Qaeda from supporting Uighur militants or propagating a jihad against China. To add to this mix, the rise of the Islamic State in Afghanistan brings anti-China militants from across the globe closer to its border. The threat of terrorists returning to China after having fought in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria has also increased in recent years, making it difficult for China to ignore the operating environment of militants in the Af-Pak region anymore.

China’s Changing Conception of Af-Pak

As a result of this, China has signaled its intention of developing a more sophisticated mechanism to engage with Afghanistan, rather than restricting itself to Kabul. The appointment of Ambassador Sun Yuxi as Special Envoy for Afghan Affairs in 2014 is one such initiative. This is also palpable in the form of increased interactions between Beijing and representatives from the Taliban, or even China’s participation in multilateral cooperation mechanisms like the Istanbul Process, whose ministerial conference it hosted in 2014. China has also played an active role in brokering peace talks in Afghanistan as one of the core members of the Quadrilateral Coordination Group. In addition, in 2016, China launched the Quadrilateral Coordination and Cooperation Mechanism that brought together the army chiefs of China, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Tajikistan to focus on securing the Wakhan corridor from terrorist organizations.

As the Afghan peace and reconciliation process moves forward, China will find itself in the unenviable position of acting tough on its long-term partner Pakistan to ensure stability in the Af-Pak region. Given its leverage with militant organizations in the region and the fact that some of them operate from within its territory, Pakistan’s role is crucial to not just fighting anti-China militant organizations, but also ensuring the success of the peace process in general. Given the strategic significance that the Pakistani military sees in its ties with these militant organizations, expecting it to change its approach will be a difficult ask. Even if Pakistan was willing to fight militancy inside and outside its borders, the crowded militant landscape that has developed in the region makes it imperative for the Taliban and its allies to ensure the longevity of their organizations, a priority that supersedes ensuring China’s security.

Ensuring Afghan Stability: With or Without Pakistan

Though China’s geopolitical heft gives it the ability to offer peace dividends to militant organizations, without involving Islamabad, it will be difficult for China to exclude Pakistan from the process altogether. China can keep individuals off the United Nations terrorist list or grant political legitimacy that comes with negotiating with an important country. But as Andrew Small has noted, given that the Afghan Taliban leadership is based in and supported by Pakistan, the reconciliation process can be “Afghan-owned, Afghan-led” but it is also “partly owned by Pakistan.” In other words, while the Taliban might not always comply with Islamabad, its geographical position and ties with other militant groups allow Pakistan to jeopardize the peace process if its interests are not met.

Furthermore, having Pakistan play an important role in the reconstruction process can be what is needed to cushion China in the future. The process so far has benefited from having a country such as the United States, which was willing to invest its military muscle, and complemented by China, whose political and economic involvement made it an appropriate mediator. A future withdrawal of U.S. forces will call for a re-calibration of international responsibility in Afghanistan. The potential global and domestic blowback of taking on Islamic militancy in Afghanistan might deter China from deploying its troops. It is here that China’s ability to get Pakistan to continue the game of “good cop/bad cop” with it will be crucial for Afghanistan’s peace process to succeed.

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

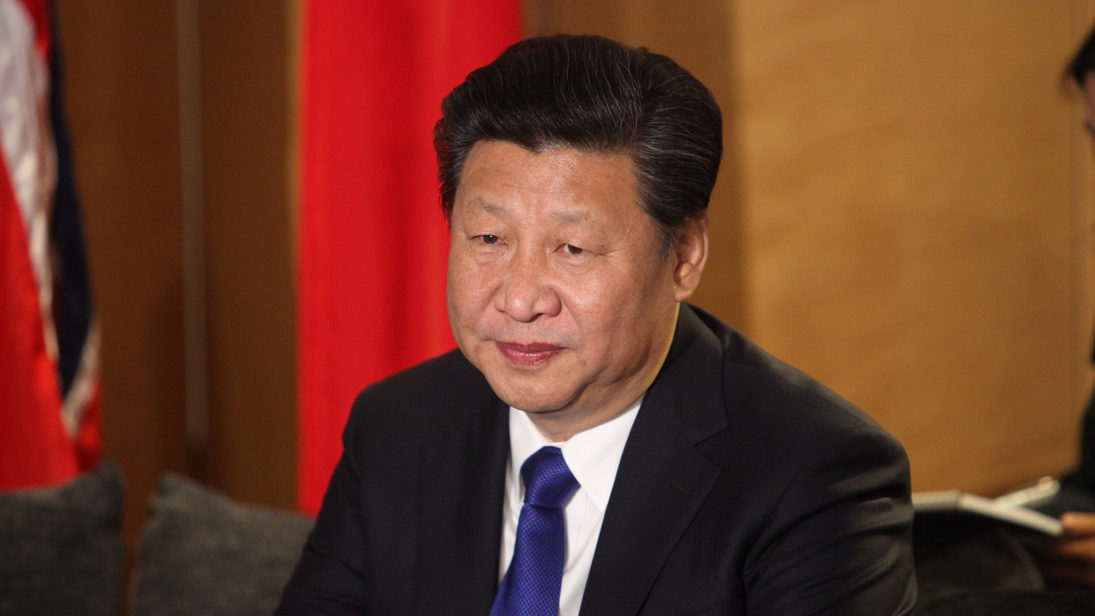

Image 1: The British Foreign and Commonwealth Office via Flickr

Image 2: Andy Wong-Pool/Getty Images