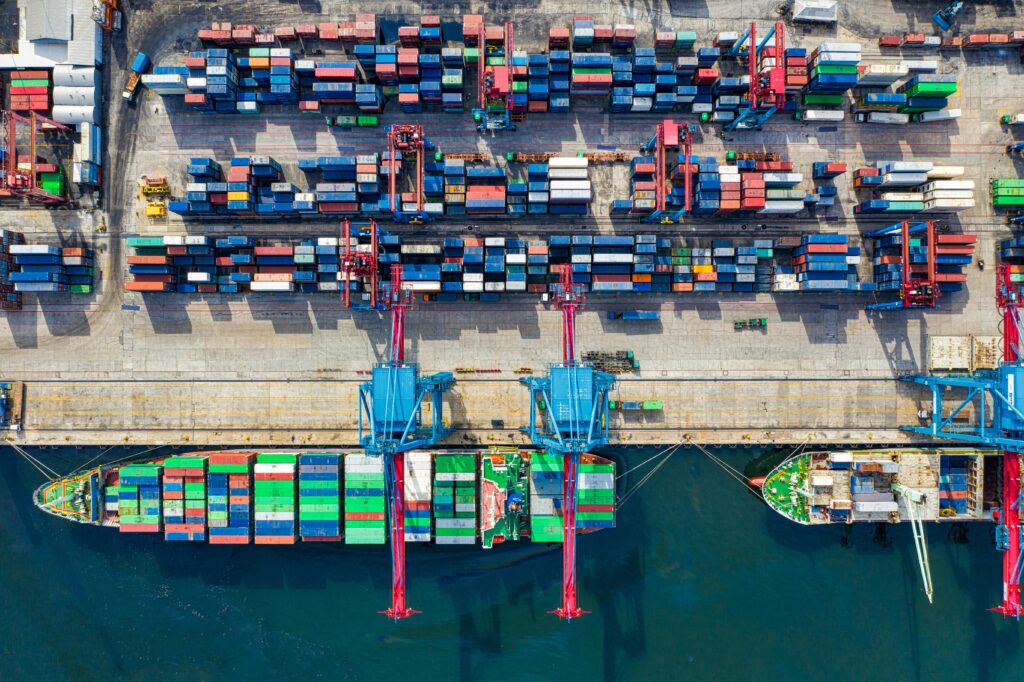

President Donald Trump’s efforts to reshape international trade are only the latest in a long list of recent disruptions that have shaken the global economy. From the COVID-19 pandemic to heightened geopolitical competition, the weaponization of economic policies, and declining trade based on labor-cost arbitrage, these disruptions have propelled developed, emerging, and developing economies and multinational firms to introduce policies that can mitigate their global supply chain vulnerabilities.

The restructuring of global supply chains creates new avenues for countries and regions to capitalize on this realignment. South Asian economies are well-placed to capture some of this global interest, particularly with companies in the search for alternatives to China that can offer low-cost, labor-intensive manufacturing. But for South Asian countries to collectively take advantage of this restructuring, they would have to consider serious reform, regional harmonization, and remove policy barriers.

“China Plus One”

The centripetal force in global supply chains is China, given its dominance in global manufacturing and its position as the world’s largest supplier of key raw materials and intermediate inputs. Over the last few years, multinational corporations have sought to escape this force and reduce their reliance on Sino-centric supply chains for a number of reasons, including the threat of a trade war between the United States and China, fears of excessive dependence on one nation, and concerns about national security in connection with the Chinese government’s possible wielding of economic and intelligence weapons.

The restructuring of global supply chains creates new avenues for countries and regions to capitalize on this realignment. […] But for South Asian countries to collectively take advantage of this restructuring, they would have to consider serious reform, regional harmonization, and remove policy barriers.

The “China Plus One” strategy – in which corporations have sought to diversify their supply chains to limit risks associated with relying entirely on China – has emerged as a cornerstone of ongoing efforts toward global supply chain realignment. This reorganization of global supply chains creates opportunities and challenges for governments, multinational corporations, and people.

At the macro level, governments have identified excessive dependence on China as a key vulnerability, and have sought to shape the supply chain restructuring to mitigate security risks and safeguard national interests. At the micro level, global businesses have been compelled to reconfigure supply chain networks to remain in sync with evolving national policies. This poses significant risks to the business models of multinational corporations as it can adversely impact their efficiency, productivity, and competitiveness. Moreover, shifting supply chains is not easy, given the complex nature of global trade networks. Aside from logistical reconfiguration, it requires significant investment in identifying new suppliers and assessing their competence on various parameters such as quality and standards. Such a scenario presents a tremendous opportunity for countries in South Asia.

South Asia’s Advantages and Gaps

With China’s transition from low-cost to high-value-added manufacturing and as global supply chains restructure, other countries and regions have significant opportunities to fill this gap in labor-intensive manufacturing. South Asian economies are well placed to offer alternative locations for this type of manufacturing due to their abundant cheap labor, growing domestic markets, and strategic geographies. South Asian economies, particularly India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, can leverage the benefits of global supply chain realignment in sectors such as garments, light engineering and low-end electronics manufacturing. Despite this, a study by Gateway House contended that multinational companies diversifying their supply chain networks away from China do not yet consider the South Asia region as a viable alternative to establishing shared production networks.

Several factors could be responsible for this. Firstly, beyond India, most South Asian economies have faced significant political instability over the past decade, which has limited their ability to offer a transparent, rules-based and predictable business environment. The current political environments of Bangladesh and Sri Lanka–which have both faced widespread protests and sudden shifts in leadership over the last few years–seem to have been a factor in impacting foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows. Sri Lanka has experienced over a 55 percent decrease in FDI inflows from 2018 to 2023. Political instability in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka has heightened the perceived risk of discriminatory and arbitrary treatment, fears of the nationalization of assets, and potential suspension of licenses as well as law and order issues. For example, the interim government of Bangladesh, which took over after the fall of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s administration, cancelled all renewable power projects in the works, including several that featured foreign companies, which now could be much more cautious in considering fresh investments.

Secondly, South Asia as a region is a relatively insignificant player in global intermediate trade. The region’s share of global intermediate goods exports was around 1.5 percent in 2021, while the share of ASEAN countries was 9 percent. Within the South Asian region, India is a key player and an active participant in global supply chain networks through backward and forward linkages. It accounts for the overwhelming majority of South Asia’s global intermediate goods exports, with a 1.9 percent global share in 2021. However, in the majority of sectors, India’s linkages with other South Asian economies remain weak. Consequently, India’s participation in global supply chains has limited spillover effects on the industrial development of other South Asia countries.

One of the key factors behind this is the low level of intra-regional trade within the subcontinent, which accounts for just 5 percent of South Asian trade. Explanations for this lack of integration include shallow trade and investment liberalization, suboptimal transport connectivity, and inadequate trade infrastructure. Another factor in South Asia’s low representation in global trade is its poor logistics performance. For instance, according to the World Bank’s 2023 Logistics Performance Index, India was ranked 38 out of 141 countries, while Bangladesh and Sri Lanka ranked 88 and 73 respectively.

A more connected South Asian region will allow countries to leverage their comparative cost advantages and trade specialization to foster regional value chain networks. For example, India specializes in the upstream segments of the textile and clothing value chain, while Bangladesh specializes in garment manufacturing. Additionally, investing in the expansion and modernization of trade and logistics infrastructure throughout South Asia will facilitate the development of regional supply chain networks. This is essential because businesses identifying potential opportunities for investment under the “China Plus One” strategy place considerable importance on the efficient movement of raw material and intermediate goods in global supply chain networks.

Thirdly, a congenial business environment is critical to attracting supply chain restructuring-led international investment. A cursory analysis of the business environments in several South Asian countries provides adequate insights into the region’s lack of competitiveness in global supply chain networks.

There are country-specific factors that affect business environments, which in turn act as a deterrent to foreign investment. India’s inability to attract investment from multinational corporations moving out of China is due to inadequate factor market reforms related to land, labor, and capital. Furthermore, India’s business landscape is still loaded with a complex web of regulatory and institutional challenges. A difficult business environment in Bangladesh was a major challenge for foreign investors even before the political upheaval of 2024. Bangladesh’s inability to garner FDI is due to a number of issues: pervasive red-tapeism, bureaucratic hurdles, delays in approvals, an anti-competitive procurement system, concerns about the violation of intellectual property rights, lack of a skilled workforce, and poor infrastructure. Sri Lanka imposes considerable restrictions on establishing a new business and prohibits the sale of public and private land to foreign firms with foreign equity exceeding 50 percent.

Policy Imperatives

In view of the changing geography of global supply chains, South Asian countries need to collaborate under a regional framework to eliminate policy-related barriers that hinder FDI in the region. For instance, they could negotiate a comprehensive trade and investment agreement between the member countries of the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation. Targeted interventions in several key areas could significantly help South Asian countries capitalize on the opportunities offered by global supply chain realignment.

South Asian countries need to focus on promoting greater harmonization of product, process, regulatory, and technical standards to eliminate the potential scope of disguised trade barriers and better facilitate the efficient movement of goods across the region

First, policymakers in South Asia would need to identify tariff lines where they have the potential to promote trade based on their comparative cost advantages and trade specializations. Regional trade liberalization would allow multinational corporations to leverage the factor endowments of individual countries, fostering regional supply chain networks. Second, trade liberalization within South Asia should be complemented by investment liberalization to attract export-oriented FDI, which is crucial to fostering strong trade and investment linkages. And third, South Asian countries need to focus on promoting greater harmonization of product, process, regulatory, and technical standards to eliminate the potential scope of disguised trade barriers and better facilitate the efficient movement of goods across the region.

The intricate and multifaceted nature of the domestic political economies of India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka coupled with their longstanding bilateral issues, such as illegal migration, water-sharing disputes, minority rights, and fishery disputes, have significantly impacted the process of regional economic integration. However, if South Asia is to take advantage of the opportunities emerging from global supply chain realignment, it will have to bracket or manage these differences while exhibiting strong political will and stakeholder buy-in.

Editor’s Note: The author acknowledges and appreciates Rohan Venkat’s inputs on this article. Views expressed are personal.

Also Read: Why BIMSTEC’s Maritime Transport Agreement is Essential for India

***

Image 1: Vidur Malhotra via Flickr

Image 2: Tom Fisk via Pexels