Since independence, Pakistan’s national identity has remained enigmatic despite religious ideology informing the fundamental rationale for the state’s existence. This enigma can be understood by examining the excessive infatuation with religious differentiation at the time of Partition which led to an excessive focus on ‘who we are not’ rather than ‘who we are’ as a nation. Even when defining the nation was attempted in the post-independence period, it was tied to an uncritical belief in the singularity of Pakistani identity and a consequent denigration of provincial identities as injurious to the Pakistani nation-state project. Take, for example, Jinnah, whose August 11, 1947, Constituent Assembly speech is celebrated as professing a liberal and secular Pakistani polity. However, this liberal attitude faded away when it came to ethnic minorities and provincial identities, which Jinnah labeled as ‘evil.’ Jinnah stated vociferously and unequivocally: “We are now all Pakistanis – not Baluchis, Pathans, Sindhis, Bengalis, Punjabis, and so on, and as Pakistanis we must feel, behave, and act, and we should be proud to be known as Pakistanis and nothing else.”

In contradistinction to the repeated focus on singularity, Pakistan’s identity is a patchwork of provincial, ethnic, tribal, and sectarian framings. These multiple layers of identity also find space in Pakistan’s foreign relations, especially with its four neighbors.

Pakistan’s religious identity finds the most expression in its relations with India. Meanwhile, regarding its western neighbor, Afghanistan, the Pakistani state’s ethnic, insurrectionist fears superseded the fraternal bond based on religious commonality. The sectarian dimension of identity comes into greater focus with Pakistan’s other Muslim neighbor, Iran, especially after the onset of the Shiite Islamic revolution. Finally, Pakistan’s religious identity was rendered irrelevant when it came to the political and strategic need of establishing enduring relations with communist China.

An important caveat when discussing identity is that it is not fixed, organic, and deterministic but instrumental and malleable. This perhaps explains why religion remained imperative at the time of Partition but was selectively applied in official matters of statecraft in the post-independence period. Moreover, while religion and singularity were central points in Pakistan’s founding, understanding when it is invoked (in relations with India) when it becomes peripheral (with Afghanistan and Iran), and when it is completely eschewed (China), elucidates how the multi-layered aspects of Pakistan’s national identity have informed its foreign policy in the region.

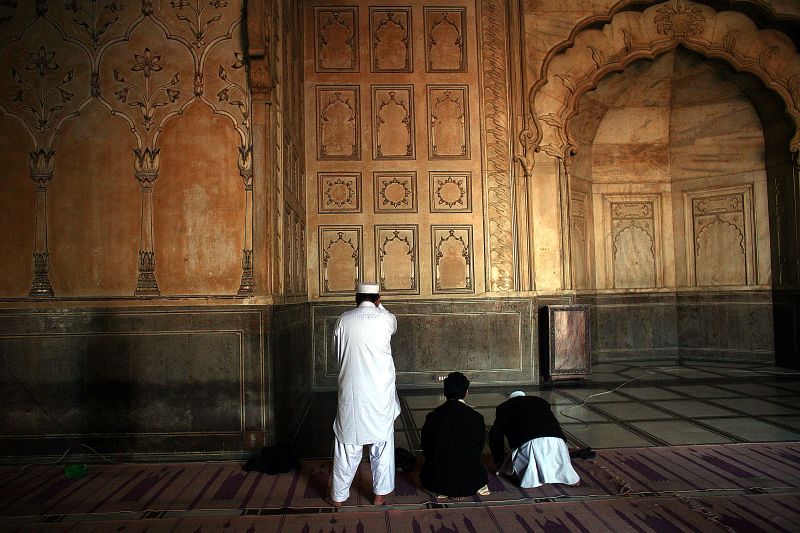

Islam and Pakistan’s foreign policy vis-à-vis India

Pakistan’s national identity at the time of independence was grounded in the two-nation theory. Propounded most succinctly by Jinnah in March 1940, he asserted that Islam and Hinduism are not merely two different religions but two separate social orders. He reiterated that “it is a dream that the Hindus and Muslims can ever evolve a common nationality. … They neither intermarry nor interdine together, and they belong to two different civilizations, which are based mainly on conflicting ideas and conceptions.”

The primary ideological perspective of Pakistan’s ruling elite has sought to differentiate Pakistan from a larger, more powerful, Hindu India. The conviction was not merely an irrational belief but was borne out of statements by Indian leaders. As late as 1963, Prime Minister Nehru argued that the “Indo-Pakistan confederation remains our ultimate end.” This ideational insecurity has acquired urgency in recent years because of India’s majoritarian turn under the current BJP leadership. The incendiary politics of hate against Muslims—not only in Kashmir but in other parts of India—including incidents of mob lynching, razing of mosques, and displacement of Muslim properties, has engendered a discourse about Jinnah’s foresightedness that Muslims would not be safe as a minority in a Hindu majority state.

The sense of being the weaker state still afflicts Pakistan’s psychological bearing with India. Various military and civilian leaders manifest this in an oft-repeated statement: “we want peace in the region, but our desire for peace should not be seen as our weakness.” In terms of identity, associating the pursuit of peace with weakness implies that a stable, positive, and confident Pakistani identity is one that comes primarily from a conviction and/or display of military strength. To this can be added that peace is as pivotal to the material sustenance and ideational consciousness of human societies as is the propensity to seek survival through strength. Second, the fact that Pakistan voices a desire for peace with India implies that the religious differentiation principle is not an impediment, should Pakistan and India make conciliatory moves toward each other.

Ethnic Claims and Insurrectionist Fears with Afghanistan

Despite the religious commonality, Pakistan’s ethnic insurrectionist fears predominate its strategic calculus towards Afghanistan, specifically its irredentist claims concerning Pakistani Pashtuns. This fear is a legacy of Partition as the Durand Line became a bone of contention between Pakistan and Afghanistan. Ironically, the insurrectionist fear continues to drive Pakistan’s foreign relations with Afghanistan. The emergence of the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM) has invited much criticism from state quarters for supposedly receiving funding and support from the Afghan security establishment. These fears are seemingly less potent now with the Taliban in power. However, the fact that the Taliban have clashed with the Pakistani forces over the Af-Pak border fencing and has not offered any assurances over the recognition of the Durand Line means that there is more than meets the eye between Pakistan and the Taliban.

Different challenges emanate from the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), who are negotiating with the Pakistani state in Afghanistan. The irony of the ongoing negotiation process is the absence of common ground between the Pakistani state and the TTP on which to base a negotiated settlement. For instance, the TTP continues to push its inflammatory agenda of disavowing Pakistan’s constitution and sovereignty by rejecting the merger of the ex-FATA region as part of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Given the history of the TTP’s bloodshed, most clearly evidenced by the APS massacre in 2014, the group has not expressed public remorse or offered any apology to the Pakistani state, society, or the grieving families to initiate a process of reconciliation. Instead, the TTP remains a highly resolved actor determined to practice Sharia in opposition to Pakistani state laws and its constitution. The negotiations with the TTP are unlikely to succeed due to the several non-negotiables between the two parties.

Sectarian Differentiation with Iran

As in the case of Afghanistan, Muslim solidarity has proven insufficient in engendering closer Pakistan-Iran ties. This became more calamitous in the wake of Iran’s Islamist revolution in the 1970s, which pushed Pakistan to hinge on sectarian differentiation and pursue closer ties with Saudi Arabia. The sectarian differentiation also manifested in Pakistan’s domestic sphere, with the proliferation of violent sectarian paramilitary jihadi groups. Iran has accused Pakistan of harboring Sunni Jundullah militants that conducted militant activities inside Iran, including the assassination of key Revolutionary Guards commanders and personnel. Recently, sources in Pakistan news media pointed fingers at Iran for providing territorial space to Baloch ethnic separatists, including Allah Nazar Baloch. While no official statement has been made, Baloch separatism emanating from Iran is an irritant in Iran-Pakistan relations.

Ideational Dynamics and Role Identity with China

Pakistan’s relations with China are often interpreted as an opportunistic alliance dictated by the presence of a common strategic competitor, India. However, this is too simplistic a reading of Pakistan-China relations, which are marked by assurances instead of threat perceptions. The India factor was less imperative in Pakistan’s diplomatic outreach to China in the 1950s. In fact, Pakistan was diplomatically efficient in engaging the Chinese, despite its participation in American-sponsored security alliances like SEATO and CENTO. At the Bandung Conference, Prime Minister Bogra convincingly argued with Chinese Prime Minister Chou En-lai that although Pakistan had joined SEATO, it had no aggressive intentions and did not consider China an aggressive power.

In doing so, Pakistan’s religious convictions were set aside as China was seen predominately as an important neighbor.

From an identity perspective, China presents a paradox, for amongst its four neighbors, it is only China with which Pakistan has pursued an emotional relationship built on phrases such as “deeper than the ocean, higher than the mountains, sweeter than honey,” “iron brothers”, and the like.

Moreover, Pakistan has consistently backed China’s position despite mounting criticism of China’s treatment of its Muslim Uyghur population.

However, the China-Pakistan relationship tethers on thin ice as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) takes shape. Perhaps the most significant test of the bilateral relationship is if CPEC affirms dependency fears emanating from a section of the Pakistani population. In such a dreaded scenario, where Pakistan’s sovereignty is weakened via the Corridor’s projects, Pakistan’s ideational affinity with the Chinese based on notions of brotherhood and solidarity will be sorely tested.

Conclusion

Religion and religious differentiation at the time of Partition continue to inform aspects of Pakistan’s foreign policy, albeit selectively. The fact that multiple layers undergird Pakistan’s identity provides grounds for inculcating diversity as a norm, rather than an exception, to the state’s identity-making project. Finally, a more confident exposition of Pakistan’s identity entails dealing with differences in ways that do not compromise more considerable cooperation within the regional and international community.

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

Image 1: Michal Svec via Flickr

Image 2: India Pakistan Wagah Border via Wikimedia Commons