In an unfortunate decision, the United Nations accommodated the Taliban’s condition to exclude women and civil society from the third meeting of Special Envoys on Afghanistan held in Doha, Qatar, to discuss how to advance international engagement on Afghanistan. Women from across Afghanistan have voiced their criticism of this decision. While proclaiming concern about the situation of women and the gross violation of their rights, many international actors have failed to meaningfully engage Afghan women and civil society when developing their policies on engagement and negotiation with the Taliban. As the UN and the broader international community move closer to normalizing diplomatic ties with the Taliban, advocates for Afghan women urge that they not lose sight of the strategic importance of women’s involvement in creating a sustainable peace for Afghanistan.

Afghan Women Advocate Against UN Decision

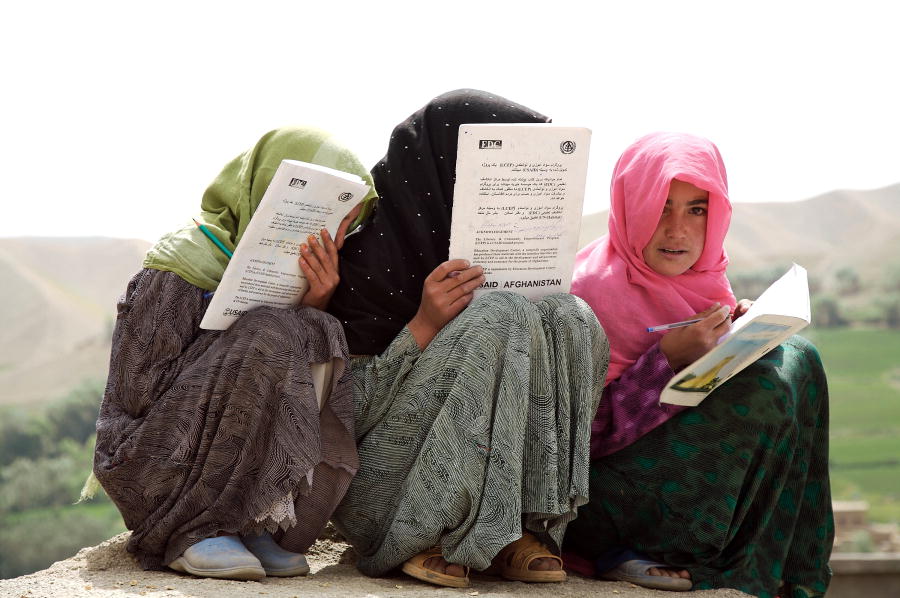

Nearly three years have passed since the country fell to the Taliban. The regime has plunged Afghanistan into a perpetual economic and humanitarian crisis, with severe consequences for the rights of women, minorities, and marginalized ethnic and religious groups. Afghanistan now holds the distinct dishonor of being the only country that prevents women from accessing formal education. The Taliban have imposed almost 100 edicts to reverse women’s hard-won rights and social gains, effectively erasing them from the public sphere. Yet, the UN, special envoys, and various officials have planned or held several meetings with the Taliban to date. Additionally, high-level UN officials, including Deputy Secretary-General Amina Mohammed and Under-Secretary-General Rosemary DiCarlo, have traveled to Afghanistan to meet with the Taliban.

Afghan women have been unequivocal in their stance: terrorists are unfit to govern Afghanistan, and the nation requires a government formed through a democratic process that guarantees women and marginalized ethnic and religious groups can exercise their social and political rights. When news broke that the UN would exclude Afghan civil society representatives, women’s rights activists, and members of opposition groups from the third Doha meeting, Afghan women demanded special envoys boycott the conference with the motto: “No women on the agenda – No women at the table – Boycott Doha3.” Afghan women from across the country have steadfastly resisted the Taliban and staged protests, endured imprisonments, torture, and even death, all in the pursuit of justice. Likewise, Afghan women outside the country continue to use every available platform to keep the spotlight on their nation and elevate the demands of women inside the country.

International Engagement Contradicts Rhetoric

Despite assurances of inclusivity, the international community for the most part has forged a one-sided, extractive relationship with Afghan women. While the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) condemns the deteriorating human rights conditions and convenes consultations, Afghan women are frequently marginalized when it comes to the international community’s decision-making on Afghanistan, with their inputs often failing to translate into actionable outcomes. This pattern existed during the U.S.-led negotiations with the Taliban in Doha before the withdrawal and persists to this day.

As the UN and the broader international community move closer to normalizing diplomatic ties with the Taliban, advocates for Afghan women urge that they not lose sight of the strategic importance of women’s involvement in creating a sustainable peace for Afghanistan.

A glaring instance is the last special envoys meeting in Doha, held on February 18 and 19. The event aimed to define the way forward for Afghanistan, focusing on counter-narcotic trafficking strategies, economic development, and the extreme poverty and food insecurity in the country. The February meeting included Afghan women but fell seriously short on their full participation. As expressed by the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, full participation means the UN-convened meeting must include women activists, civil society members, and politicians in core discussions as decision-makers. The UN excluded representatives from closed-door meetings where critical negotiations took place and did not keep representatives informed. They were also not granted a meeting with Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, which highlights the lack of genuine commitment to meaningful inclusion and dialogue and emboldens the Taliban. These efforts are a testament to the growing de facto recognition of the Taliban, with the UN and various special envoys bending over backward to appease them.

The UN has continued to prioritize political engagement with the Taliban, assuming that bringing them to the negotiation table would lead to progress on other fronts. The prevailing thought, as expressed in June by the special envoy from China, is that the international community will need to effectively accept the political reality in Afghanistan in order to address issues such as narcotics trafficking and development, ultimately pushing the Taliban to moderate as they “gradually become more trusting to the outside world.” The Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Afghanistan stressed in a public statement on June 21 that “engagement” is not normalization.

This is an inherent contradiction. By excluding Afghan women and civil society representatives from the agenda of the third meeting, UMAMA sidelines the leading voices on the future of Afghanistan’s political process and humanitarian needs. This signals a de facto recognition of the Taliban and a normalization of “engagement” without any tangible changes on the ground. Alongside UNAMA’s “engagement,” the Taliban have only escalated their attacks on women, warning the international community that issues such as girls’ education are internal matters.

“Engagement” with the Taliban on Afghanistan’s security or economic conditions, in exchange for a concession on human rights, will not compel the Taliban to change. The Taliban have touted the UN’s invitation as an acknowledgment of their administration’s growing global significance and legitimacy. Meanwhile, they have openly stated that they have not and will not change. Their all-male, majority Pashtun cabinet is further evidence of their exclusionary and regressive policies. The Taliban have proven incapable and unwilling to govern Afghanistan in an inclusive manner that embraces the diversity of the country and ensures women’s rights and their participation in public life.

Afghan women’s full participation in future Doha meetings is not merely a symbolic issue but a strategic imperative for multilateral forums to build sustainable peace. The Under-Secretary-General and Special Envoys’ July 2 meeting with representatives of Afghan civil society and women’s rights advocates after the main event, is a token gesture by the UN and fails to genuinely acknowledge their importance in the deliberations.

UNAMA’s approach will not enhance security in Afghanistan or worldwide. The UN’s decision to exclude Afghan women and civil society members from the core agenda will damage the international community’s long-term objective of stability since they provide the most essential perspective on addressing their country’s humanitarian and governance needs. Nearly three years under Taliban rule have severely damaged the economy due to a lack of inclusive governance; excluding women from certain employment sectors has resulted in an annual economic loss of USD $1 billion. The Taliban’s ban on women’s employment in international NGOs restricts women’s access to much-needed humanitarian assistance. The Taliban’s corruption and interference in the aid delivery process also deprive marginalized communities of essential support.

Women’s perspectives are essential to creating a feasible roadmap for Afghanistan’s future since they understand the needs of Afghanistan’s marginalized communities, and their involvement ensures that policies and interventions are inclusive and effective. They have raised their voices against targeted killings of Hazaras and former military and government officials by the Taliban. Afghan women have also been the only group consistently making inclusive human rights demands since the failed U.S.-led peace process. Ignoring the women of Afghanistan means not only excluding them but undermining their demands for a prosperous Afghanistan for all, including marginalized ethnic and religious groups, Taliban opposition groups, and LGBTQ+ communities.

Afghan Women’s Key Demands to the International Community

Responsible international bodies must hold the Taliban accountable for grave human rights violations – including attacks on women, the Hazara ethnic minority, their persecution of LGBTQI individuals, and extrajudicial killing of former military officials — by refusing normalization or recognition of the Taliban unless they adhere to international human rights principles. The UN must not grant a seat at the table to the Taliban, and individual governments must refuse to open their diplomatic missions in the country. If the UN continues with the same approach, it will set a precedent that emboldens the Taliban and fails to address the most serious issue facing Afghanistan’s prosperity: the Taliban’s exclusion of half the country’s population from the workforce and public life.

The Afghan human rights community and international human rights organizations demand that the UN Security Council refer the Taliban to the International Criminal Court Prosecutor for the crime of gender persecution and label the Taliban’s treatment of women as gender apartheid, a crucial demand articulated by the women of Afghanistan. The UN must also pressure the Taliban to reverse all 100 edicts that have erased women from the public sphere.

Afghan women have also been the only group consistently making inclusive human rights demands since the failed U.S.-led peace process.

The UN Security Council must further sustain and strengthen travel bans and sanctions designations on Taliban members. Just as Afghan women are restricted from traveling, the same should apply to the Taliban. Donor governments must provide funding and political support to women-led civic groups to expand their much-needed work, and women must be fully engaged in all conversations about the future of Afghanistan.

The UN’s future Special Envoy of the Secretary-General must recognize that one of the most critical crises facing Afghanistan today is its women’s rights crisis. The deteriorating rights conditions for women only worsen the humanitarian situation and prevent a comprehensive response to entailing security issues. A survey by the Organization for Policy Research and Development Studies (DROPS) revealed that most Afghan women prioritize women’s rights as their primary concern, followed by access to public services.

The UN and the broader international community cannot dismiss that Afghan women’s full, meaningful participation in multilateral deliberations is crucial to building sustainable peace in Afghanistan. Excluding women from future Doha meetings, no matter how productive, will only serve to undermine the credibility and effectiveness of the Doha process and embolden the Taliban to violate the rights of its citizens unabated.

Also Read: Charting Afghanistan’s Economic Future: Recommendations for Reform.

***

Image 1: Women in Afghanistan via Flickr.

Image 2: Young Girls Prepare for Exams in Afghanistan via Flickr.