Even as India-Bangladesh ties have seen signs of economic and political stress in recent days and weeks, one recent development with bilateral implications went largely unnoticed. On June 20, Bangladesh became the first South Asian country to accede to the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes (Water Convention), a treaty promoting equitable and sustainable management of transboundary watercourses. The Water Convention was adopted in 1992 as a regional framework under the aegis of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE)—initially a regional agreement, it was opened to all UN Member States in 2016. The Water Convention requires parties to use transboundary waters reasonably and equitably, ensure sustainable water management, and prevent significant harm to neighbors.

The timing of Bangladesh’s accession is significant as it comes during heightened political tension in the region and a fierce legal and diplomatic debate triggered by India’s decision to hold the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) with Pakistan in abeyance after the Pahalgam terror attack in April. As water stress—compounded by geopolitics and environmental factors—increases in South Asia, Bangladesh’s accession to the Water Convention signals a new reality: bilateralism alone can no longer serve India’s hydropolitical interests in an increasingly unpredictable regional landscape.

Bangladesh’s Motivations

The immediate reasons cited by Bangladesh for accession to the Water Convention were the increasing impacts of environmental change, population growth, and rising water demand, which make water cooperation a necessity.

For a downstream nation with 57 rivers, joining the Water Convention is a strategic move by Bangladesh to internationalize its water concerns and push for stronger legal mechanisms to govern rivers like the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna. As a lower riparian state, Bangladesh is dependent on transboundary rivers for its freshwater resources, generating uncertainty in its water management. During the monsoon season, Bangladesh faces the persistent threat of devastating floods; in the dry season, it faces severe droughts, impacting both agriculture and water security.

Bangladesh’s accession to the Water Convention signals a new reality: bilateralism alone can no longer serve India’s hydropolitical interests in an increasingly unpredictable regional landscape.

The increasingly acute impacts of climate change along with rising domestic water demand compound Bangladesh’s water challenge further. Though the country has highlighted that it has been engaging with the UNECE treaty framework for over a decade, the major discourses on water governance in South Asia are centered around the 1997 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses (UNWC), a global agreement as compared to the UNECE pact which began as a regional convention for Europe.

Bangladesh’s decision to join the Water Convention instead of the UNWC stems from the fact that the former moves beyond legal norms to focus instead on robust mechanisms, technical and financial assistance, and institutional support for sustainable and equitable water sharing. It also obliges member states to establish joint institutions and receive technical and financial support through the Meeting of the Parties connected with the use, protection, and management of transboundary waters. Since 2016, the Water Convention has expanded to include non-European countries. As of now, 15 non-European countries such as Iraq, Namibia, Ghana, and Senegal have become parties to the Water Convention with more than 20 countries in the various stages of accession.

Implications for India

India is not a party to the Water Convention or the UNWC and has taken the stance that water is a state rather than a federal matter, which impacts the central government’s ability to implement international water agreements. This is because while India’s federal structure allows the central government to negotiate and sign international treaties even on state subjects, implementation may require cooperation from states. For instance, the proposed Teesta River Water Sharing Agreement in 2011 was shelved due to objections from the West Bengal state government.

India also objects to third-party involvement and has preferred to address water issues through bilateral agreements, such as the Indus Waters Treaty and the 1996 Ganges Water Treaty (GWT) with Bangladesh. However, India’s bilateral diplomacy is under strain. Following the killing of civilians in Pahalgam, India announced that the IWT with Pakistan would be kept in abeyance. The Mahakali Treaty with Nepal also faces challenges with implementation due to mistrust and hydropolitics with China are increasingly strained given its dam construction on the Brahmaputra (Yarlung Tsangpo), a project that may cause India and Bangladesh grave ecological risk, including threats of flooding. India plans to counter China’s dam construction by building its own dam on the Siang river, a tributary of the Brahmaputra, which could cause further ecological and geopolitical risk for India, China, and Bangladesh.

Critically, the GWT is up for renewal in 2026. In June 2024, India’s foreign secretary announced that the Indian and Bangladeshi governments would soon begin discussing the renewal. Yet, more recent reports suggest that instead of a renewal, New Delhi is looking for a fresh agreement to account for irrigation, port maintenance, and rising power demands. While such details are not available in the public domain, it can be argued that this move, along with India’s abeyance of the IWT, gives the impression of a lack of willingness on New Delhi’s part to share its waters. Such perceptions could have influenced Bangladesh’s recent decision to join the Water Convention, though no direct evidence explicitly links the two developments.

India is facing acute water stress, with states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh facing chronic shortages. Flash floods and glacier melt have consequences for hazard risk and food and water security in the heavily populated Himalayan regions. While India may try to resolve these issues domestically or even bilaterally, it is evident that hydropolitics and the impacts of environmental change transcend borders. India continues to rely on bilateral agreements as an upper riparian state but given Bangladesh’s signaling and China’s increasingly prominent role in regional hydropolitics, New Delhi should consider whether bilateralism continues to serve its aims.

Regional Impacts

Bangladesh’s accession to the Water Convention carries major diplomatic significance, projecting the nation as committed to the cooperative management of transboundary waters and a regional first mover. Bangladesh will likely rely on the Water Convention provisions and push for a more equitable, transparent, and climate-resilient agreement on Ganges water sharing with India beyond the current dry season allocations. Currently, the agreement provides 35,000 cusecs of water alternately for 10 days each to both countries during the dry period. Following the Water Convention guidelines, Dhaka will likely insist on regulated environmental flows and a legally binding dispute resolution mechanism. If India resists these demands for formal, institutionalized mechanisms in water sharing, it could face international pressure and risk undermining its global leadership in climate negotiations.

If India resists these demands for formal, institutionalized mechanisms in water sharing, it could face international pressure and risk undermining its global leadership in climate negotiations.

Bangladesh’s accession could also likely trigger other countries in the region, including Nepal, Bhutan, and Pakistan, to accede to the UNECE framework. While India and Pakistan abstained from voting on joining the UNWC when it was introduced at the UN General Assembly, Bangladesh, Nepal, and the Maldives supported it. Given this precedent, it is plausible that other South Asian countries may also accede to the Water Convention. Such a move would shift regional hydropolitical dynamics toward multilateral governance, putting pressure on India to accede as well.

South Asia has no basin-wide monitoring mechanism, no institution for environmental risk coordination, and no legal mechanisms to demand transparency from upper riparian countries. In the past, bilateralism was effective because hydropolitical disputes were relatively contained, and weather variability was not as pronounced, allowing states to negotiate bilateral arrangements without the complexity of multilateral frameworks. Today, however, these conditions have changed. Increasing climate change, population growth, growing water stress, and more fragmented regional politics have strained bilateral channels. As Bangladesh sets a regional precedent, India stands at a crossroads. It can continue to rely solely on bilateralism, which was effective in the past but is increasingly fraught, or it can move towards cooperative mechanisms for water governance and geopolitical stability in South Asia. For this, New Delhi can begin with considering accession to the Water Convention or the UNWC. This move would enable India to position itself as a responsible regional power committed to sustainability and peaceful cooperation over transboundary waters, especially amidst increasing environmental and growth pressures.

Views expressed are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the positions of South Asian Voices, the Stimson Center, or our supporters.

Also Read: Strategic Waters: The Indus Treaty Abeyance and South Asia’s Hydropolitical Future

***

Image 1: Teesta River in Sikkim – Indivar Das Goswami via Wikimedia Commons

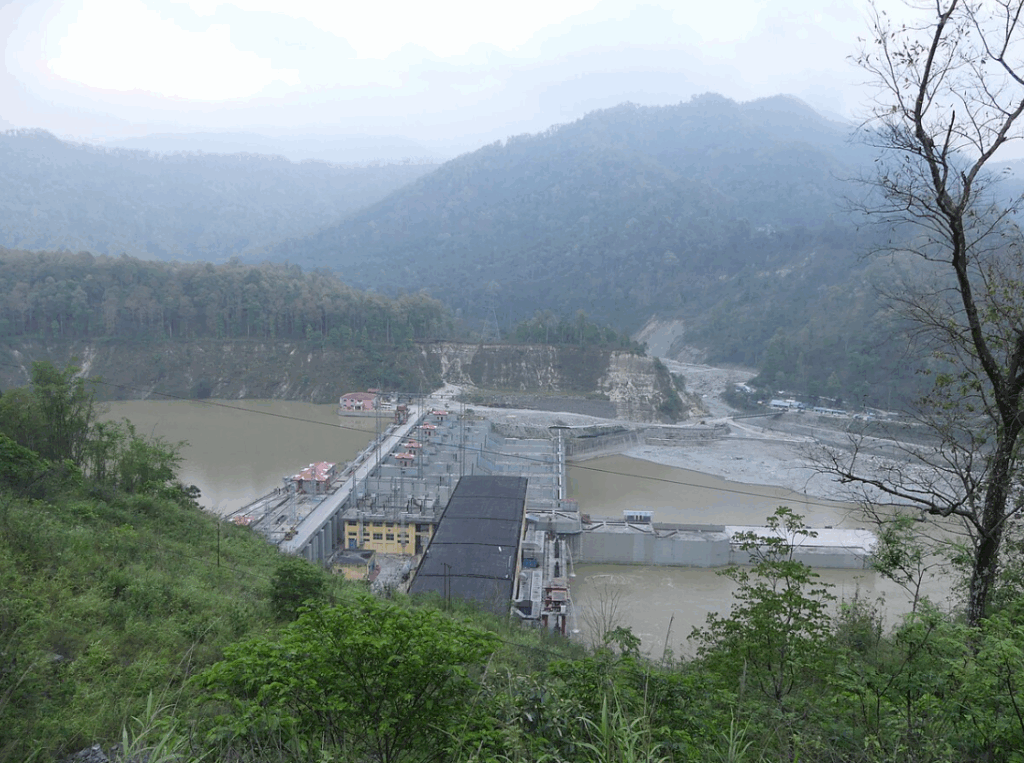

Image 2: Teesta Low Dam III in West Bengal – A. J. T. Johnsingh via Wikimedia Commons