The India-China geopolitical rivalry has traditionally been viewed through a continental lens, with the border dispute between the neighbors overshadowing other aspects of their competition. However, as the continental neighbors command the seas and secure their interests, the island countries of the Indian Ocean have emerged as new sites of economic and political contestation between Beijing and New Delhi. This was evident during the recent presidential elections in the Maldives and Sri Lanka, and in recent developments in the Western Indian Ocean (WIO) islands, such as the Comoros, Madagascar, Seychelles, and Mauritius. Despite enjoying a head start through early historical engagement in the region, India is now falling behind China in this simmering competition. New Delhi must take corrective action to become a partner of choice in the region before Beijing elbows it out.

History: A Common Denominator

Nearly two centuries ago, India was a source of indentured laborers in many Indian Ocean states. However, Beijing, too, had similar if relatively lesser-known ties to the island countries of Mauritius, Seychelles and Madagascar. Through the 1800s, people from southern China migrated to the WIO islands to work on colonial plantations. These historical trends have given the two modern-day powers strong diasporic linkages, cultural commonalities, and economic ties with the island nations.

Following their independence in the 1960s and 1970s, India leveraged these historical ties to build diplomatic, defense, and developmental partnerships with various Indian Ocean states. In 1981, New Delhi concluded a trade agreement with the Maldives. India also helped establish the Seychelles Defense Academy and the Mahatma Gandhi Institute in Mauritius. Militarily, New Delhi was also involved in multiple interventions in the region, including Operation Flowers Are Blooming in 1986 and Operation Cactus in 1988, in Seychelles and the Maldives respectively. Through such operations, India was able not only to project its power in the maritime neighborhood but also to preserve and protect political stability.

While China too has engaged with the WIO states since their independence, the region has only acquired strategic significance for Beijing since the turn of the twenty-first century. Unlike New Delhi, Beijing has taken a more mercantilist approach, and several Chinese companies have expanded their footprint in the region, intertwined with Beijing’s growing political influence and military presence. In some cases, this approach has proved controversial and unpopular.

Although New Delhi had established its presence in the Indian Ocean region decades ahead of Beijing, its footprint in the region has paled in comparison to China’s in more recent years.

Falling Behind Beijing

Although New Delhi had established its presence in the Indian Ocean region decades ahead of Beijing, its footprint in the region has paled in comparison to China’s in more recent years. While China has diplomatic missions in all six island countries of the Indian Ocean, New Delhi only has missions in five countries; the mission in Madagascar combines the work of Comoros too. Despite its historical ties to the islands, India has not attempted to stitch the region into a holistic construct. Beijing engages with the island nations under region-wide mechanisms like the China-Indian Ocean Region Forum and Forum on China-Africa Cooperation. New Delhi has also tried to spearhead maritime security initiatives like the Colombo Security Conclave. However, the grouping’s membership is limited and does not include all the island nations of the Indian Ocean. India has also suffered on occasion from political changes in the countries, such as when Maldivian President Mohamed Muizzu came to power in 2023 and initially pivoted to Beijing. By contrast, Beijing has been able to garner support for its One China policy among the island countries through proactive engagement.

On trade, while both India and China enjoy trade surpluses with each of the island nations, Beijing exports a more diversified basket of goods. Chinese exports dominate capital intensive industries such as heavy machinery, electrical appliances, electrical batteries, boat propellers, delivery trucks, cranes, and furniture, while Indian products are largely agricultural (with one exception being Seychelles). This diversity gives Beijing not only a bigger footprint in the region but also more strategic leverage. By exporting capital goods as opposed to consumer-centric agricultural products, China is able to make inroads into diverse sectors of the receiving countries, generate greater profit margins, and aid in the development of manufacturing.

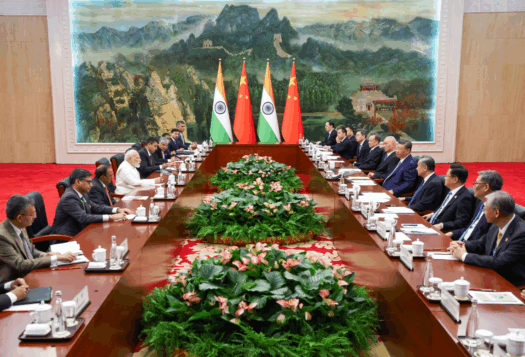

China’s economic footprint also manifests through the role played by its public and private sectors in these strategically located countries. Beijing is an active dispenser of aid and channelizes investment through overseas NGOs and private organizations, spearheading infrastructure development and community-oriented projects that meet the specific needs of these island countries. For instance, in the island of Comoros, which sits atop a crucial maritime waterway and is a treasure trove of hydrocarbon reserves and critical rare earth minerals, Beijing is playing an active role. Through initiatives geared towards the elimination of malaria, and the building of critical infrastructure such as roads, airport complexes, stadiums, and government buildings, China has come to acquire an all-pervading presence in Comoros. By contrast, New Delhi continues to rely excessively on existing state mechanisms like public sector enterprises and the footprint of its private sector is mostly limited to large conglomerates.

China is also growing its military footprint in the region. According to a report by the U.S. Department of Defense, out of the few sites shortlisted by Beijing for overseas military facilities, several are located in the Indian Ocean. Among these, there are reports that Comoros may host the next Chinese base in the Indian Ocean. In this regard, Beijing is regularly sending survey-cum-research vessels, involved in deep-sea exploration and the collection of critical data related to underwater topography, salinity, oceanic currents, and the surroundings, which assist in deep-sea mining. Moreover, as part of grey zone warfare, Chinese sponsored maritime militia are operating as civilian fishing fleets, with a close association with both the Chinese Coast Guard and the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN). In 2024, China signed a secret defense deal with the Maldives at a time when Indian defense personnel were asked to leave the Maldives. These developments have helped feed the perception in New Delhi of the growing maritime threat and substantial risks posed by Beijing to India’s national security and broader strategic interests.

Bridging the Gap

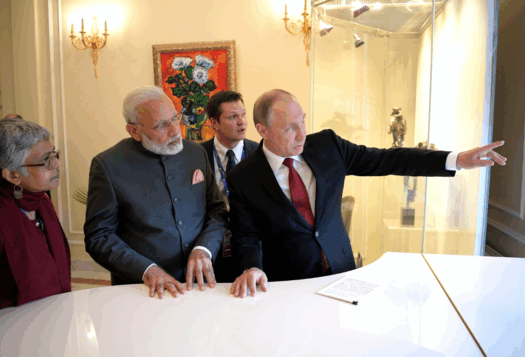

Unlike the fierce competition in the continental neighborhood, in the maritime sphere, India and China are locked in a precursory stage of stiff competition, aimed at gaining more influence in the strategically located island countries of the Indian Ocean. In 2015, in an attempt to catch up with Beijing’s burgeoning influence, India launched the Security and Growth for All in the Region (SAGAR) framework which revamped New Delhi’s role in the Indian Ocean. This was later expanded to the Mutual and Holistic Advancement for Security and Growth (MAHASAGAR) vision to further ensure collaboration and integration. In 2024, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi invited the heads of the Indian Ocean island states to his swearing-in ceremony to start his third term in power. In the same year, to deal with the evolving nature of challenges, India also upgraded an airstrip and developed a jetty in the Agalega islands of Mauritius which would allow larger aircraft like P8I Poseidon to operate for surveillance and reconnaissance. The fully developed jetty would also allow larger ships to anchor at the harbor and undertake humanitarian operations.

Nonetheless, to compete with China, New Delhi should still take several steps to consolidate its role as a net security provider and a central regional player in the Indian Ocean.

First, India needs to step up its diplomatic, institutional, military, and economic engagement with the island countries as it makes a shift to MAHASAGAR. In particular, New Delhi should focus on nurturing institutional arrangements that can lend stability to the relationship in times of domestic political changes.

India needs to step up its diplomatic, institutional, military, and economic engagement with the island countries as it makes a shift to MAHASAGAR.

Second, as island nations are the first line of defense both in times of war and peace, India needs to step up its military cooperation. This should not only include the appointment of more defense attachés but should also ensure defense cooperation in advanced modernized weapons that meet the needs of the islanders, including advanced surveillance drones and large military vessels that can assist in patrolling their large EEZs. Additionally, New Delhi should continue providing capacity building to armed personnel in these nations and offer more courses of instruction in India.

Third, besides a greater emphasis on capital goods, industries such as tourism and cinema offer prime opportunities to diversify the economic basket. The Indian Ocean islands are hotspots of ecology and tourism, and despite India’s historical and diasporic ties to these countries, many of them receive more tourists from Europe. New Delhi should institutionalize cooperation with tourism agencies to promote them as tourist destinations to Indians as well. In the same vein, as one of the largest producers of feature films in the world, India’s film industry can play a role in promoting these scenic destinations to Indian audiences and building cultural ties between India and the Indian Ocean states. To further diversify economic ties, efforts must also be taken to institutionalize private sector cooperation across economic sectors such as food and beverage, hospitality, transport, and communications.

Last but not least, in each country, New Delhi must cultivate relations with political parties across the spectrum. Leaning too heavily toward parties with which it shares historical ties does not bode well for a country that aspires to maintain a dominant influence in the region. The likely success of this diversified approach can be seen in Mauritius where, unlike in the Maldives, New Delhi has cultivated ties with all major political parties, and the relationship has continued to grow despite changes in government.

India’s leadership in the Indian Ocean region is critical to achieve its geopolitical and economic objectives, as noted in a recent report by the Indian Parliamentary Committee on External Affairs. However, to do so effectively, India must exhibit openness, accommodation, and understanding toward the island countries, maintaining the fine balance between diplomacy and dominance, tradition and transformation, and influence and integrity.

Also Read: The Indian Ocean’s Maritime Security Dilemma

Views expressed are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the positions of South Asian Voices, the Stimson Center, or our supporters.

***

Image 1: Foreign dignitaries, including from the Maldives, Mauritius, and Seychelles, attend PM Modi’s third swearing in ceremony on June 9, 2024 – Narendra Modi via X

Image 2: Chinese and Comorian presidents meet on September 2, 2024, in Beijing – PRC State Council