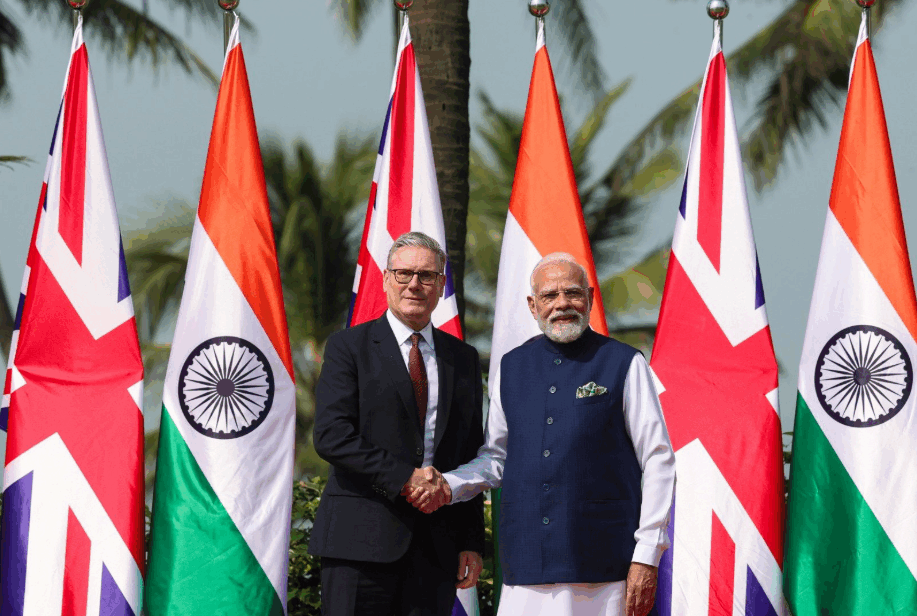

Last month, British Prime Minister Keir Starmer led an unprecedented 125 member trade delegation to Mumbai, building upon the India-United Kingdom Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) signed three months ago during Indian Prime Minister Modi’s visit to London. For his first official visit to India, Starmer bypassed the political pomp of New Delhi to anchor his visit in the country’s financial capital—at a time when U.S. trade policy has ushered in an era of tremendous geoeconomic fragmentation.

Downing Street has positioned this reinvigorated India partnership as a cornerstone of its post-Brexit economic strategy. Since Britain’s exit from the European Union, successive British governments—Johnson, Truss, Sunak, and now Starmer—have consistently prioritized deepening relations with India, anchoring it in Indo-Pacific security, expanding trade and investment, advancing technology cooperation, and nurturing the people-to-people connections that serve as a “living bridge” between the two nations. Starmer returned from Mumbai with concrete results: GBP £1.3 billion (USD $1.7 billion) in new Indian investment pledges expected to create over 10,000 jobs across technology, engineering, and education.

In India, the visit sent a strong message to both domestic and international audiences that despite U.S. President Donald Trump declaring the Indian economy “dead,” its global economic pull remains strong. Following a painstaking, multiyear negotiation process, the deal signaled to international partners that India is increasingly ready to open up its markets to developed economies. The strategic logic of this growing partnership is driven by the shifting contours of international politics: as India pursues strategic autonomy amid mounting economic nationalism and geopolitical uncertainty, the UK offers a critical middle-power partnership focused on mutual economic growth, defense cooperation, and technological innovation.

Foundations: Trade and Technology

The top item on Starmer’s agenda for the Mumbai visit was to set the ball rolling on the implementation of CETA—described in London as the “biggest and most economically significant bilateral trade deal the UK has done” since Brexit and “the best deal India has ever agreed.” Their bilateral trade, which currently stands at around USD $56 billion, is expected to double over the next five years, with the agreement adding 0.13% and 0.06% each year to UK and Indian GDP, respectively. Under the deal, 85 percent of UK exports—from whisky and agricultural goods to aerospace equipment—will eventually enter India tariff-free, while 99 percent of Indian exports will face zero duties in the UK. The visit also saw the establishment of a “fintech corridor” between both global financial technology hotspots to augment cross-border payments and AI-driven financial services. Multiple UK universities received approvals to set up campuses in India, and Starmer invited India’s large film industry to produce “BollyBrit” movies in the UK.

“As India pursues strategic autonomy amid mounting economic nationalism and geopolitical uncertainty, the UK offers a critical middle-power partnership focused on mutual economic growth, defense cooperation, and technological innovation.”

Emerging tech has become an increasingly significant area of focus, with New Delhi and London viewing their partnership in this space from a security lens. A part of the ambitious India-UK Vision 2035, tech cooperation largely covers investment opportunities and research partnerships across critical minerals, artificial intelligence (AI), quantum, telecom, chips, biotechnology, and advanced materials. Just a year after its formation, this partnership has already set up joint centers on AI, Non-Terrestrial Networks, and cyber security and a guild to deliver investment in critical minerals supply chains. Notably, New Delhi’s only other tech partnership this deeply rooted in strategic intent—and led by both National Security Advisors—is with Washington, under the U.S.–India TRUST (“Transforming the Relationship Utilizing Strategic Technology”), the successor to the Biden-era U.S.-India Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology (iCET).

Growing Defense Ties

Defense cooperation is another pillar of the bilateral relationship. As part of Vision 2035, India and the UK have been working towards the adoption of a 10-year Defence Industrial Roadmap that emphasizes co-production over procurement in line with the Modi government’s “aatmanirbharta” (“self reliance”) and “Make in India” goals. Two key defense deals were announced during the Starmer visit: joint development of maritime electric propulsion systems for Indian naval platforms, and a GBP £350 million (USD $461 million) deal to deliver UK-built Lightweight Multirole Missiles to the Indian Army.

The visit coincided with the Royal Navy’s carrier strike group conducting Exercise Konkan with the Indian Navy in the Western Indian Ocean, the first time in history that a UK and Indian carrier strike group participated in an exercise together. This development follows the deployment of the UK carrier strike group to the Indian Ocean in 2021, when the UK officially affirmed its “tilt” to the Indo-Pacific. Both countries also announced that they will set up a Regional Maritime Security Centre of Excellence under the Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative, aimed at, as India’s former Chief of Naval Staff Admiral Karambir Singh put it, “developing human capital for the maritime domain.” Maritime engagement, therefore, is becoming the backbone of their security partnership, reflecting both nations’ evolution as blue-water powers with increasingly convergent Indo-Pacific interests: balancing China’s presence to keep this strategically vital region free, open, prosperous, secure, and multipolar.

Limitations: Domestic Politics, Strategic Shifts

Despite the intent shown by both governments, the India-UK partnership still faces significant challenges. In the defense portfolio, for instance, the relationship lacks the institutional scaffolding seen in India’s ties with its closest partners. While two editions of the “2+2 Foreign and Defence Dialogue” between India and the UK have taken place, these remain senior official-level meetings rather than ministerial-level dialogues like those New Delhi maintains with the United States, Japan, Australia, and Russia. Meanwhile, London’s deeper integration with AUKUS partners and Japan—all embedded within the U.S. alliance architecture—provides it with denser defense frameworks and operational alignment. India’s preference for strategic autonomy and reluctance toward formal alliances—stemming largely from its colonial past—imposes unique constraints on the institutionalization of defense ties with the UK.

Domestic politics also occasionally constrains the India-UK relationship. A host of sensitive historical or sovereignty concerns, some rooted in the legacy of colonial rule, can engender periodic mistrust between the two polities. In the UK, subcontinental diaspora politics—especially around Khalistan and Kashmir—occasionally generate security concerns and political sensitivities. Recent years have witnessed violent protests, threats to Indian diplomats, and broader challenges to India’s interests, complicating the bilateral relationship. Furthermore, growing anti-immigration sentiment in the UK has generated political challenges, especially related to visas for Indian nationals.

The strategic logic of the growing India-UK partnership could also be on shaky ground. This year, Starmer’s Labour government has had to “focus urgently on European security” in response to the Trump administration’s approach to the transatlantic relationship. For one, in the European theater, India’s longstanding ties with Russia run counter to UK priorities; but more importantly, greater UK policy attention and resource allocation to European security could distract from shared India-UK interests in the Indo-Pacific.

Middle Power Partnerships: Indian Foreign Policy Pivot

The aforementioned challenges notwithstanding, from New Delhi’s perspective, this growing partnership fits squarely within India’s evolving foreign policy agenda: building substantive, agenda-heavy relationships with a diverse network of middle powers. Over the last few months, India has welcomed Australia’s first defense trade mission, signed a Declaration on Security Cooperation with Japan, and is working towards an EU-India Security and Defence Partnership.

This flurry of diplomatic activity comes against the backdrop of great uncertainty about the global priorities of the new U.S. administration. Upon the election of Donald Trump in November 2024, New Delhi was among the capitals most confident of steady relations with the United States, but today finds itself on the sharper edge of a new era in U.S. foreign policy. India received among the highest effective tariff rates on its exports to the United States, with an additional 25 percent duty tied to Russian energy purchases—seen by some as selective punishment to coerce trade concessions and retaliate for New Delhi’s dismissal of any U.S. role in the India-Pakistan ceasefire. Once a strong critic of Pakistan, following the May 2025 India-Pakistan crisis, President Trump has pursued closer ties with Islamabad and “rehyphenated” India and Pakistan through frequent claims of mediation. The United States, once enthusiastic about engaging India as a counterweight to China, now flirts with the idea of a U.S.-China “G2,” undercutting the central logic of U.S.-India partnership in the twenty-first century.

Despite this “storm” in the relationship, however, the United States remains India’s most important bilateral partner across most areas, including economy, security, and technology. In any case, India does not have levers—like, for instance, China’s rare earth monopoly—to get the upper hand in its negotiations with Washington. India’s strategy for now is necessarily pragmatic: wait, watch, and widen.

“From New Delhi’s perspective, this growing partnership fits squarely within India’s evolving foreign policy agenda: building substantive, agenda-heavy relationships with a diverse network of middle powers.”

In practice, this has created space and incentive for India to cultivate an arc of middle-power partnerships, with the UK, Australia, Japan, the EU, France, Russia, the UAE, Israel and others each filling a niche in India’s broader resilience architecture—strengthening New Delhi’s ability to withstand and adapt to global uncertainties and disruptions.

There has been a practical recalibration of India’s approach toward China as well. While in the works for some time post-Galwan, strained ties with the White House widened the opening for normalized ties with Beijing. In the short term, this means India will fuel its manufacturing ambitions with access to Chinese equipment and critical materials, at least until self-reliance goals mature.

India’s ties with the UK may not command the same spotlight as Washington or Beijing, but they capture the recalibration of world politics today. As both countries navigate economic nationalism and geopolitical flux, their partnership offers a template for what pragmatic, interest-driven middle-power cooperation can look like. Over the past few years, both sides have invested significant political and diplomatic capital in the relationship. The task now is to channel that momentum into mechanisms that deliver on trade, defense, and technology—Indian Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri’s visit to London in early November to follow through on the understandings reached during Starmer’s India trip represents an excellent first step. If they succeed, the India-UK partnership could emerge as a critical steadying force in the Indo-Pacific and beyond.

Views expressed are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the positions of South Asian Voices, the Stimson Center, or our supporters.

Also Read: Quo Vadis, Indian Foreign Policy? The Perks and Perils of Multialignment

***

Image 1: Narendra Modi via X

Image 2: Narendra Modi via X