Amidst debates concerning a possible overhaul in New Delhi’s strategy towards the, Taliban— since the group swiftly took over Kabul in August—the voices of hundreds of Afghan refugees in the country seems to have drowned out. Just a few days after the Indian government announced an emergency e-visa facility for Afghan nations to expedite their entry into the country, hundreds of Afghans nationals who fled from their country earlier protested outside the New Delhi UNHCR office, demanding refugee status. According to the UNHCR New Delhi Factsheet from September 2021, India currently hosts 15,769 refuges and asylum seekers. The lack of data makes it difficult to determine the exact ethno-religious composition of Afghan refugees in the country. Historically, refugee populations have been composed mostly of Hindus and Sikhs. The poor living conditions of Muslim Afghan refugees in India is well documented, but even Afghan Hindus and Sikhs struggle with poverty and abysmal living conditions. According to UN records, Afghan refugees constitute one of the world’s largest refugee populations, with more than 2.2 million refugees worldwide. UN refugee agency estimates that half a million people could flee across the border by the end of this year, indicating the urgency of the deteriorating humanitarian situation in Taliban controlled Afghanistan.

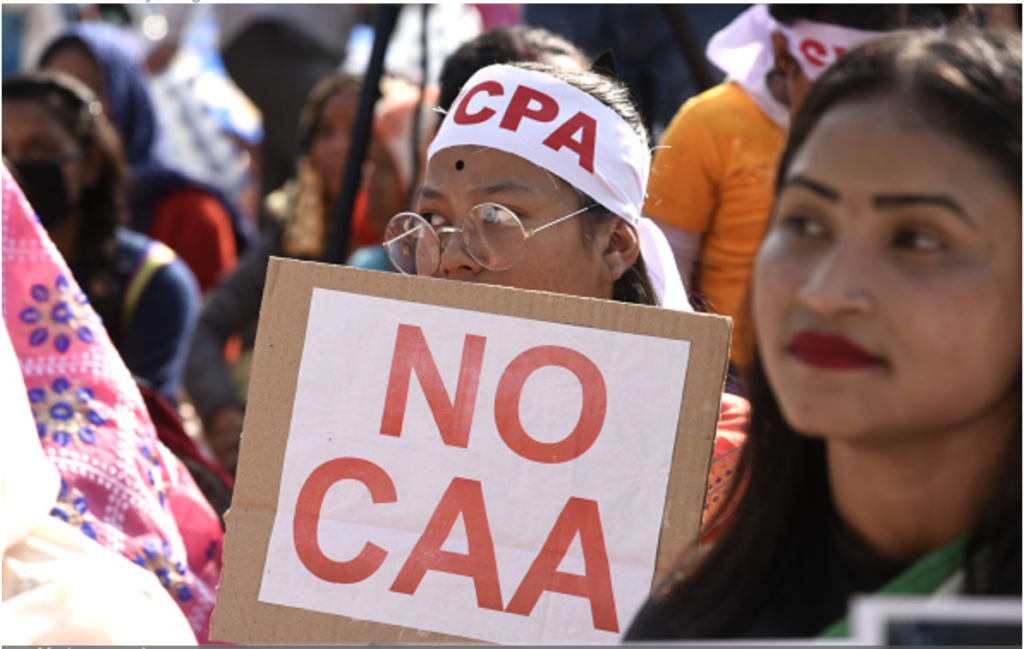

In 2019, the BJP government passed the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which grants citizenship to non-Muslim “illegal immigrants” who entered the country on or before December 31, 2014 from the three Muslim-majority countries neighboring India, namely Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. Without mentioning the word “refugee”—as India does not make a distinction between refugees and illegal immigrants—the act uses religion as a criterion for determining who will or will not receive state protection among groups facing religious-religious persecution. It was not surprising to see the current government proceed with selective prioritization of Sikh and Hindu Afghans in repatriating refugees from Afghanistan.

As an important regional player and one of Afghanistan’s largest Asian donors, India could play a major role in easing Afghanistan’s humanitarian crisis. Several countries have recognized New Delhi’s importance in managing the Afghan crisis, and lauded its leadership in steering a global consensus on Afghanistan in the deeply polarized United Nations Security Council. However, India’s changed domestic political environment—embodied in the CAA and other majoritarian policies—has already miffed its neighbors and created serious challenges for its “Neighbourhood First” policy. At a time when India is competing with China for influence in South Asia, such a legally enforced discriminatory stance on refugees handicaps New Delhi’s efforts to play a regional leadership role.

India’s Ad-Hoc Refugee Policy

In 2013, Antonio Guterres, then United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and currently the Secretary General of the United Nations, described India’s refugee policy as an “example for the rest of the world to follow.” Home to over 200,000 refugees from Sri Lanka and Tibet and over 40,000 refugees and asylum seekers of other nationalities, India has a long tradition of welcoming refugees. Despite being one of the few liberal democratic countries not a signatory to the 1951 UN Convention relating to the status of refugees and the 1967 protocol thereon, India has received several waves of refugees from neighboring countries— including during the 1947 partition and Bangladeshi independence after the 1971 Indo-Pakistani War. Except Afghanistan, none of the South Asian countries are party to the convention, largely due to the porous nature of borders in South Asia, which poses unprecedented challenges to a region ill-equipped to deal with the contemporary refugee challenge.

At a time when India is competing with China for influence in South Asia, such a legally enforced discriminatory stance on refugees handicaps New Delhi’s efforts to play a regional leadership role.

In the absence of clearly defined statutory standards, refugee protection in India has been governed by arbitrary government policies and case-specific judicial interventions. As there is no clearly defined category of refugees under Indian law, either the Indian government or the UNHCR has determined the extent of protection refugee populations receive. A closer look reveals that the government’s record has been inconsistent in managing refugees, where official policy has clearly been influenced more by political equations than by legal and humanitarian considerations. This was evident when Sri Lankan refugees who were originally welcomed into the country were forcibly repatriated without international supervision, following the assassination of then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in the 1980s by a suspected member of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. The revival of majoritarian politics in 2014 under the current Modi government—after over a decade of coalition governments—has guaranteed a similar fate for refugees seeking asylum in India. This time, religion has become the means of discrimination.

Religious Litmus Test for Refugees

In a widely criticized move, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government has been deporting Rohingya (who are mostly Muslim) refugees in contravention to the international norm of non-refoulment, by playing up a “terrorism” threat. Several voices in the country directly alluded to and justified the government’s “religious” motivation for the decision—to create a rashtra (nation) of Hindus, by Hindus and for Hindus.

The persecution of the Hazara Shi’a Muslims and other non-Sunni Muslims—labeled heretical by the Taliban—serves as an unfortunate reminder of how hollow the distinctions made by CAA are.

Anti-Muslim sentiment has been on the rise since the Modi government came to power, which together with the governments systematic anti-minority policies, has specifically made Muslim refugees a target. The government’s commitment to protect Hindus, which took practical form in the CAA, reflects the government’s ideological stance—Muslims are seen as the perpetrators of violence in these countries, while Hindus are the victims as the constitutions of the three countries provide for a specific state religion. While it is true that non-Muslim minorities do face discrimination and persecution, it is also true that Muslim minorities, expressly not covered by the Act—which wrongly homogenizes the Muslim community—face a similar fate. Hazara Shi’a Muslims and other non-Sunni Muslims—labeled heretical by the Taliban—have been victims of the groups targeted violence, which serves as an unfortunate reminder of how hollow the distinctions made by CAA are. Those supporting the current governments blatant religious discrimination towards Afghan refugees point towards the dwindling number of Sikhs and Hindus in the country, projecting India as their last bastion of hope for survival. While it is true that a large number of Hindus have left Afghanistan to evade religious discrimination, not all wish to go back to India and some even returned back to Afghanistan, despite the threat of religious persecution. Others still have sought resettlement in the United States and Canada.

International Isolation over Discriminatory Policies

For a country which prides itself on its secular and democratic heritage and civilizational tradition of atithi devo bhava (the guest is god) India’s current position on the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan risks international isolation. Anti-CAA criticism is not confined to within India’s borders—international citizens, government actors and bodies such as UNHCR have called out the discriminatory nature of the act. On one hand, the Indian government is championing a “unified” response to the Afghanistan humanitarian crisis, on the other it has refrained from critically evaluating its own actions and policies on the issue. There is no easy answer to the enormity of the refugee crisis in South Asia which entails massive economic costs to build necessary infrastructure, the real possibility of radicalization of refugees, and abuse of refugee laws. But it is clear that religious discrimination is not the answer. The massive Afghan refugee crisis is the latest reminder that the current government’s approach is shaped far more by Hindutva politics than by genuine humanitarian considerations.

***