In a recent bilateral meeting between India’s Prime Minister Modi and Russia’s President Vladimir Putin during the SCO summit in Uzbekistan, Modi made headline-making comments on the war in Ukraine, stating that “now is not an era of war” and expressing disquiet over the prolongation of the conflict. This is a major departure, as India has not expressed its displeasure in public with respect to the war in Ukraine. Since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war, India has maintained a lopsided neutrality, placing a stronger emphasis on its relationship with Russia and failing to balance its ties with Ukraine. A stance that ultimately undermines India’s position in the rapidly changing international security landscape.

While India recently reversed its long-held practice of UN abstentions by voting against Russia at the United Nations Security Council on August 24th and subsequently announced its 12th consignment of aid to Ukraine, it has nonetheless failed to project its neutrality by not cultivating further ties with Ukraine to offset its strong ties to Russia. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has not spoken with his Ukrainian counterpart, President Volodymyr Zelensky, since the evacuation of Indian students from Ukraine in March. Meanwhile, India’s National Security Advisor met with his Russian counterpart last month, and the Indian army joined for the VOSTOK military exercise in Russia in early September. India has also increased its purchases of Russian oil. The Ukrainian foreign minister recently slammed India with his remarks, saying, “When India purchases Russian crude oil, they have to understand that the discount has to be paid by Ukrainian blood.”

Since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war, India has maintained a lopsided neutrality, placing a stronger emphasis on its relationship with Russia and failing to balance its ties with Ukraine. A stance that ultimately undermines India’s position in the rapidly changing international security landscape.

India’s long-term goal is to become a major player on the international stage without entering any alliances requires stable conditions and a multipolar world. India’s interests could be harmed by the current Russia-Ukraine conflict, which could make Russia less of an independent pole. To avoid this, India’s multi-alignment strategy could benefit from a position that stresses neutrality by maintaining a balanced engagement with both Russia and Ukraine and proactively supports the mediation process.

India as a Mediator

In the immediate aftermath of Russia’s invasion, the former Ukrainian ambassador to India issued a rallying cry for India to utilize its influence to settle the crisis. Likewise, when Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov visited India in April, he expressed an openness to the possibility of India mediating the conflict. In the opinion of former Singaporean diplomat Kishore Mahbubani, India is best suited to mediate the dispute between Ukraine and Russia because it is one of the few countries that enjoy good will in both Washington and Moscow. For India, engaging in the mediation process would also increase its stature on the world stage. The idea of third-party mediation is not new to India, as it has played a major role in the Cold War in supporting a peaceful resolution to conflicts.

During the Korean War, India played a pivotal role as a mediator and proposed a resolution that offered the essential means to end the Korean War and eventually resulted in the signing of the Armistice Agreement. Though this agreement did not end with a termination of the conflict, it helped establish a Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission, chaired by India, to determine the fate of more than 20,000 prisoners of war from both sides. Despite various setbacks in the mediation process of the Korean War, India’s role elevated its stature among the newly independent Afro-Asian countries as a diplomatic negotiator.

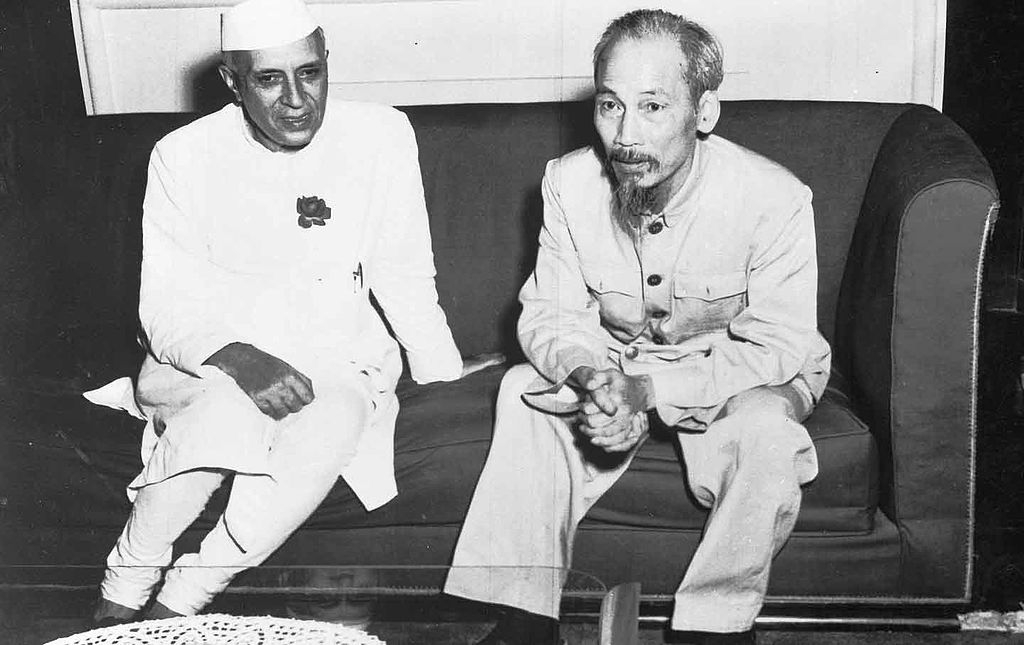

From 1954-65 India chaired the International Commission for Supervision and Control, established in one of the successful resolutions at the Geneva conference after the first Indochina War (Vietnam War). Despite a widespread perception that the Commission ultimately failed, it delivered several successful results during its early phase and its failure is largely attributable to the Commission’s inadequate mandate. The overall objective of India’s foreign policy was to prevent the involvement of large powers in India’s extended neighborhood. India’s engagement can be attributed to the fact that the potential instability in other parts of Asia could harm its interests. India believed that it would spread outside of East and Southeast Asia and constrain the resources needed for its development.

Mediation Setbacks

India’s role in mediating conflicts was severely hampered by its wars with China and Pakistan in 1962 and 1965, which ultimately led to a shift in India’s foreign policy from one of peacemaker to security seeker. The shift entails, defining India’s interests in narrower terms and a regional image centered on a subcontinent as opposed to an expansive Asian space, acceptance of balance of power as a norm, and a willingness to use force was no longer avoided.

Although India has adopted a more securitized approach to its foreign policy, it has never been reluctant to mediate a conflict when it was requested to do so. In 1987-88, when Vietnam decided to withdraw its troops from Cambodia, Nguyen Co Thach, the former foreign minister of Vietnam, requested India to convey Vietnam’s decision to ASEAN countries. Immediately recognizing the importance of the request from Hanoi, then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi sent India’s former Minister of State for External Affairs, Natwar Singh, to serve as a special envoy to Vietnam and other ASEAN nations in an effort to end the Vietnam invasion of Cambodia. With this action, Natwar Singh was undertaking the equivalent of shuttle diplomacy.

Historically, India’s approach towards mediation was not borne out of idealism, but rather a well-calibrated policy approach to suit its interests.

However, India’s policy of not employing third-party mediation on its own disputes in Kashmir has prevented it from actively intervening in conflicts in other regions. As this effort may attract the focus of the third-party mediation to India’s own issues in Kashmir. India has never formally offered to mediate in any conflicts since the end of the Cold War. Even while leaders from the Middle East, including Palestine, Syria, and Israel, have at regular intervals expressed interest in India playing a constructive role in the Middle East Peace Process, India has been reluctant to do so.

Linking the Past and the Present

India’s actions reflect the geopolitical interests that flow from its geography and history. During the Cold War, Delhi became involved in the Korean War and the Vietnam War to maintain peace and order in the region, which had implications for India’s interests. Likewise, in the current international security landscape, it is prudent for India to have an integrated approach when it comes to geography, as both the Indo-Pacific and the Eurasian theater need to be treated as a single geographic space. As the ongoing Ukraine-Russia conflict demonstrates, instability in Eurasia has direct economic and security implications for the Indo-Pacific and vice versa.

Historically, India’s approach towards mediation was not borne out of idealism, but rather a well-calibrated policy approach to suit its interests. It is likewise in India’s best interest to make every effort possible to prevent Russia from becoming China’s “junior partner.” India has steadfastly maintained its ties with Russia, however, a weakened Russia will be vulnerable to China’s diktats and it would constrain India’s space in the region which are important to its economic and security interest which includes Eurasia, Indo-Pacific, and potentially the Arctic region. If India intends to maintain a balanced relationship with Russia, it should not be concerned about the possibility of Russia’s reprisals for engaging with Ukrainian policymakers. As a result of its isolation from the west, Russia has less incentives to sour its ties with India.

Finally, India’s position is progressively altering in response to developments on the ground. The lightning-fast onslaught by Kyiv, which saw its military forces seize some significant cities in the Northeast of the nation that has been occupied by Russia, must push India to step up its engagement with Ukraine, and be open to mediating the conflict. If Russia is looking for a face-saving exit India should express its intent to mediate, as India has the capabilities and experience to play a meaningful role in ending the war.

***

Image 1: ALEXANDR DEMYANCHUK/SPUTNIK/AFP via Getty Images

Image 2: via Wikimedia Commons