In the 70 years of India’s diplomatic engagement with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the economic component of that relationship has shown tremendous dynamism. While the general Indian population barely takes note of it today, the intensity and complexity of India’s economic relations with its northern neighbor is a relatively new phenomenon. From virtually nothing in the 1960s, India’s trade with China reached USD $95 billion in 2018. The PRC is India’s second largest trading partner and facilitating ever larger cross-border capital flows. Despite recurring security tensions, the India-China economic relationship can potentially provide further growth opportunities, however, new challenges including pandemic-induced low domestic growth and insular tendencies pose a serious threat to the future of the relationship.

India-China Early Economic Relations: The First 30 Years

Despite their close geographical proximity, the early years of India and China’s economic relationship is best understood by its obstacles. Several related historical factors suppressed economic engagement between India and China even as diplomatic relations were established in 1949. The two countries’ colonial histories meant that comparative advantages and supply chains were configured to serve colonial interests in what were naturally unsustainable arrangements. British India’s opium trade with China whose purpose was to finance British imports of Chinese commodities is a case in point. Colonial history further left both economies impoverished and focused on internal reconstruction. Moreover, mutual antipathy towards external engagements also kept both countries insistent on a development model predicated upon import substitution – a policy that calls for replacing trade with domestic production.

According to data collected by the Correlates of War project, between 1950 and 1960 India and China’s total bilateral trade stood at a meager USD $225 million (unadjusted). Making matters worse, the Sino-Indian war of 1962 over border disputes single-handedly brought economic relations to a near total halt, a condition that persisted for roughly the next two decades. India’s China policy in its totality became inextricably linked with the border question, precluding any advancements in structurally burdened economic relations.

Despite recurring security tensions, the India-China economic relationship can potentially provide further growth opportunities, however, new challenges including pandemic-induced low domestic growth and insular tendencies pose a serious threat to the future of the relationship.

Economic Relations: The 1980s Onward

Broadly speaking, structural transformation in both the Indian and Chinese economies has been instrumental in promoting economic exchange since the 1980s. On the one hand, China changed track from the Maoist tradition of zealous import substitution and state driven industrialization to a more market based and growth oriented model that generated large manufacturing activity and, consequently, the necessity to create value from foreign demand.

As economic growth became a salient priority for policymakers throughout China, access to India’s billion strong, low income market emerged as a strong incentive for cooperation. In the late 1980s economic growth also took center stage in India under the leadership of Prime Ministers Rajiv Gandhi and P.V. Narasimha Rao, resulting in incentives to jettison rigid import substitution and decouple the economic and security domains to a certain extent in relations with China. Prime Minister Gandhi’s visit to China in 1988 saw the creation of two separate Joint Working Groups, one on the boundary issues and the other ways in which the structural changes in the two economies could be translated into greater economic and scientific cooperation.

Bilateral trade drivers only intensified as the floodgates opened, generating significant advantages for both economies. After China joined the WTO in 2001, the country’s economy shifted up the value chain of manufacturing, generating demand for raw materials. India possessed a comparative advantage in these commodities, leading to intensified trade between the two countries. In the 2001 to 2008 period, India supplied roughly a fifth of China’s total iron ore imports in addition to large proportions of cotton and copper – though trade patterns are changing with China’s move up the manufacturing value chain. On the flip side, Indian demand for electronic goods is almost entirely supplied by Chinese exporters, thus playing a significant role in India’s digital drive and helping drive bilateral trade up to USD $95 billion in 2018. Robust capital accumulation in both countries coupled with large foreign reserves are also driving cross-border investments. Chinese corporations have offered capital to some of India’s most well known tech startups such as Paytm in e-commerce and Swiggy and Zomato in food delivery. Improved economic relations have therefore played a pivotal role in the two countries’ development.

This is not to say that stumbling blocks have been eliminated. Indian officials often decry the widening trade deficit with China, blaming their northern neighbor for protecting industries from Indian competition, a factor that played a role in India’s refusal to join the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Chinese officials meanwhile contend that deficits with trading partners results from the fact that they are consumption-oriented economies with a relatively weak manufacturing base, which necessitates more imports. The security element of the India-China relationship also occasionally rears its head in the economic domain, particularly in India’s telecom sector. For instance, the Indian armed forces have expressed displeasure and raised security concerns over Huawei’s role in India’s telecom infrastructure and the Government of India has been carefully contemplating banning Huawei from India’s 5G trials.

COVID-19 and the Future of Sino-Indian Economic Ties

None of these obstacles, however, detract from the broad mandate of economic engagement. With more dedicated bilateral mechanisms in place, individual episodes at the border in recent years have ultimately done little to impact the economic relationship. While U.S.-China trade tensions could potentially disrupt aspects of the India-China trade relationship, these are more likely to be more of a logistical cost as opposed to fractured ties. A decision to ban Huawei from India’s 5G infrastructure would likewise only generate punitive costs as opposed to a broad decoupling.

The relationship does, however, face a more existential threat of a COVID-19 induced global recession, which is likely to adversely impact the India-China economic relationship through multiple channels. The precipitous loss of household incomes and demand in both countries will naturally hit bilateral trade hard—even modest slowdowns in the two economies’ growth levels in 2019 led to a USD $3 billion reduction in trade levels year-on-year. Moreover, the pandemic has also prompted India to act on long standing concerns regarding predatory Chinese acquisitions of companies of critical nature (banks, data-intensive firms) by mandating screening of foreign direct investments. Given the uncertainty surrounding the specifics of the screening process and China’s capacity to retaliate against Indian investors under their foreign investment law, this could potentially shock cross-border capital flows.

The relationship does, however, face a more existential threat of a COVID-19 induced global recessions, which is likely to adversely impact the India-China economic relationship through multiple channels.

Most importantly, the pandemic is not a short-term, logistical hindrance but has the potential to drive both countries back to a policy emphasizing import substitution—a process that appears to have already begun in India’s case. To be sure, India’s adherence to principles of open trade had already suffered somewhat in recent years with new tariffs, including those on electronic items imported from China. The pandemic appears to be amplifying those tendencies with calls for self-reliance now being touted in speeches at the Prime Ministerial level. India’s COVID-19 stimulus package directs government agencies to strictly procure supplies locally and build domestic competitiveness through protective non-tariff barriers and state support to handpicked industries.

Policymakers, however, should resist the urge to return to a policy of self-reliance. As noted earlier, these preferences have a track record of suppressing economic relations directly as well as hampering productivity and domestic growth. Despite hurdles, Indian consumers and Chinese producers have benefited substantially from the exchange of cheap raw materials and manufactures, and it is imperative to account for the impacts of this on general welfare.

Perhaps more importantly though, Indian policymakers should view the Chinese market as a potential export growth opportunity—global trade has a tendency to strongly rebounded after economic crises and India’s USD $3 trillion economy possesses the ingredients and scale to be a major supplier to the over USD $13 trillion consumption-oriented middle income Chinese market. Sacrificing these growth avenues at the altar of self-reliance entails large opportunity costs of income and welfare in two huge economies. So much so, that it would not be far fetched to posit that the future of Indian, Asian, and global growth hinges on the trajectory of the India-China economic relationship.

Editors Note: As India and China mark 70 years of diplomatic ties, SAV contributors look back at Sino-Indian economic, political, and strategic relations since 1950 and analyze trends to watch for in the years ahead. The full series can be viewed here.

***

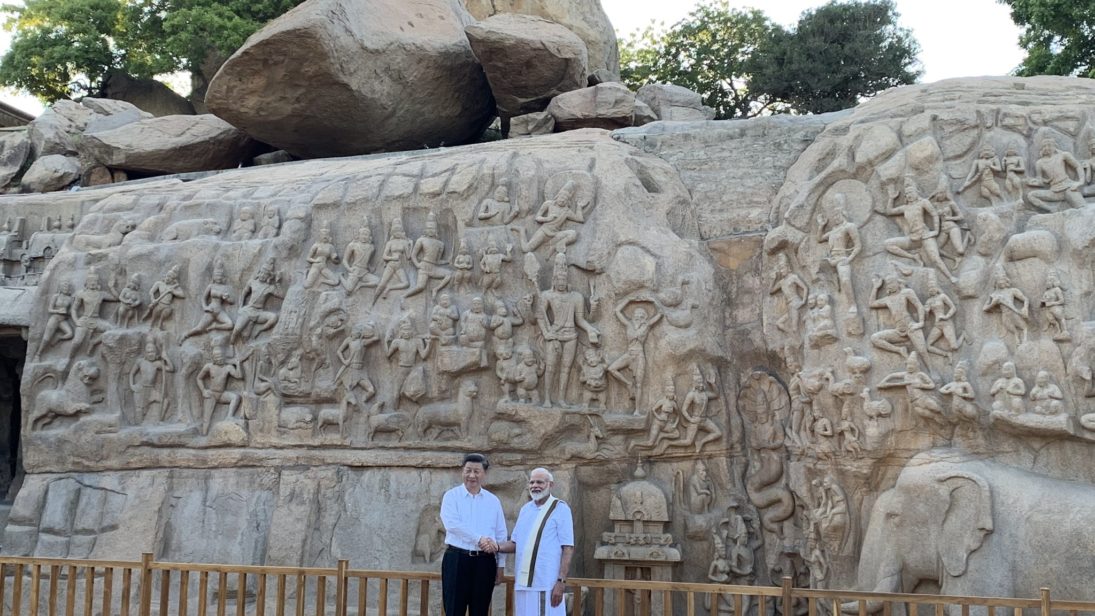

Image 1: Office of the Prime Minister of India via Twitter

Image 2: Str4nd via Wikimedia Commons