Bangladesh’s Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina is set to visit Beijing from July 3 to 5 to sign several agreements and memoranda of understanding (MoUs) with her Chinese counterpart, but the visit has come against the backdrop of a clash between hundreds of Chinese and Bangladeshi workers at a power plant site in southern Bangladesh – the latest bout of violence against Chinese-led and -funded projects in South Asia. While the two sides are eager to strengthen their economic cooperation, it will be interesting to see whether they will also discuss the power plant site incident.

Hasina’svisit and the clashes highlight that there are growing apprehensions in SouthAsia toward China’s strategic rise, though Beijing’s economic cooperation andinvestment has benefited the region and helped to balance India’s dominatingregional presence. Thesesentiments stem from the potentially strategic and opaque nature of Chinese-fundedinfrastructure projects as well as South Asia’s historical experiences andfears of great power domination.

Regional Perceptions of Chinese Projects

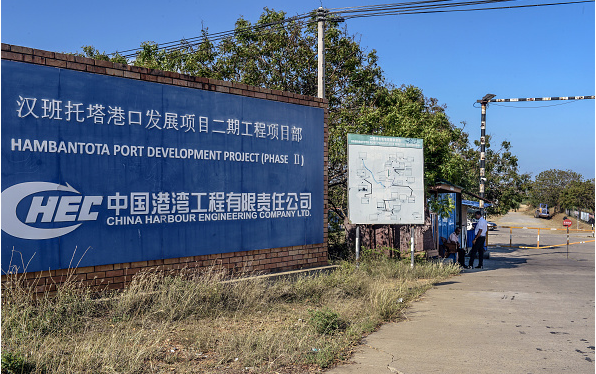

All South Asian countries barring India have either endorsed or joined China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in recent years. Some flagship projects include the Gwadar port in Pakistan’s Balochistan province as well as the Hambantota port and Colombo International Container Terminal (CICT) of Colombo port in Sri Lanka. China has managed to secure these assets via long-term contracts in order to reduce debt payments, securing the Gwadar, Hambantota, and CICT ports on 40-, 99-, and 35-year leases respectively. The length of these leases has raised concerns over China’s intentions in the region, particularly since it does not make economic sense for China to take over the transfer of operation of Gwadar port when private investors like Singapore’s PSA International deemed it to be commercially unviable. Many feasibility studies have also shown that Hambantota is unable to compete with the Colombo port, and thus will not be an economically viable asset. This has spread a narrative among many in policy and academic circles within and outside of South Asia that China is investing in these ports to achieve broader strategic interests and project power at sea, since these ports are part of major trade routes and international supply chains.

Chinese developments are also viewed by some locals as usurpation and exploitation of their country’s resources. For instance, in Sri Lanka, there are concerns that Hambantota port could become a naval facility for the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy. Unlike Colombo, where the Sri Lanka Navy is stationed, Hambantota could provide space for Chinese military vessels. Similarly, in the Maldives and Pakistan, the new governments of President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih and Prime Minister Imran Khan have questioned the long-term profitability and viability of Chinese projects in their respective nations. Both Solih and Khan ordered a review of Chinese-funded infrastructure projects soon after their respective electoral victories.

Like the recent clashes in Bangladesh, there have also been instances of violent backlash in Pakistan. In August 2018, the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) attacked a busload of Chinese engineers in Dalbadin district, wounding five people, including three Chinese engineers working on a Pakistan-China joint project. Similarly, in late November, the BLA attacked the Chinese consulate in Karachi, killing four. Even after the death of BLA leaders, including their commander, Aslam Baloch, in a suicide blast in Afghanistan, the group has vowed to continue attacks on BRI projects in the region. While it is too early to assess if Chinese projects can indeed deliver economic gains, they risk intensifying tensions between the state and smaller federal units and provinces such as Pakistan’s Balochistan and Sindh over alleged unfair economic development and resource distribution.

These attacks and incidents are not simply a response towards rogue practices and non-transparency of Chinese projects; they are a consequence of South Asia’s history. There are extant lingering fears rooted in historical experiences of colonial exploitation. From this history emerges a deep resentment to regional hegemony as well. For example, India’s structural dominance and policies in the region have garnered much resentment and suspicion in South Asian governments and publics, tilting neighboring states in favor of China to counter the strategic imbalance. India’s strategic ambitions in South Asia and consequential foreign policies to achieve political gains has caused many South Asian nations to view its actions as an interventionist posture. It led them to perceive India as a regional bully and fanned varying degrees of anti-India sentiments – which continue to be exploited by various political parties in the region to bolster nationalist credentials, shore up support, and gain electoral victories. By making a bid for regional primacy, China is making the same mistake that India did and exacerbating domestic opposition to BRI.

These attacks and incidents are not simply a response towards rogue practices and non-transparency of Chinese projects; they are a consequence of South Asia’s history.

Chartinga Way Forward

The tides seem to be turning. Increasingly, South Asian states are reassessing the terms of their engagement with China and re-establishing ties with India. For instance, Sri Lanka recently agreed to jointly develop the East Container Terminal (ECT) of Colombo Port with India and Japan. While anti-China sentiment in South Asian nations may intensify, these countries are unlikely to sever relations with China as Beijing remains critical to managing India’s regional clout.

To avoid appearing aggressive, China should shift away from muscle-flexing and make more conscientious efforts to take on the role of a benevolent power in the region. It can do so by diversifying and emphasizing its soft power. China’s soaring economy has elevated the country: it is now an economic model that many countries wish to emulate. The country also has a rich and ancient cultural heritage and boasts of many soft power sources such as art, architecture, food, and medicine.

China is already leveraging these tools to build a benign image in the world. In South Asia, it has established Confucius Institutes in Nepal, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka to promote social and culture exchanges. Beijing also offers scholarships to South Asian students to pursue higher studies and research in China. In November 2018, China started offering visa on arrival for Bangladeshi citizens who want to visit China for urgent humanitarian, business, and other grounds.

If soft power is to work, a country’s narrative needs to be consistent with its conduct. Attitudes toward China will hinge on the nature of Chinese interactions with the full spectrum of stakeholders at the local, regional, and national levels. China may need to be more transparent about its infrastructure projects, including BRI, in order not to be perceived as exploitative, especially given South Asian sensitivities toward dominating by great powers. Some reforms could include implementing multilateral rules and including local stakeholders in host countries to avoid appearing opaque and hegemonic. It is already setting up a panel of international mediators to resolve multiparty disputes arising from BRI projects, but it could also partner with international organizations such as the Asian Development Bank or the World Bank in order to appear inclusive, objective, and transparent.

If soft power is to work, a country’s narrative needs to be consistent with its conduct. Attitudes toward China will hinge on the nature of Chinese interactions with the full spectrum of stakeholders at the local, regional, and national levels.

As for soft power, China needs to encourage and actively facilitate more people-to-people contact with South Asian countries to complement traditional and formal diplomacy. This can be done through socio-cultural, religious, and educational exchanges with limited supervision from the state to develop greater understanding between the different communities. This may in turn facilitate positive sentiments about China and garner public support for its presence in the region. Beijing should also soften its aggressive domestic stance on human rights in its own country. By cracking down on human rights activists and repressing dissent, China not only hampers the potential of its civil society, but also undercut soft power potential in South Asia.

***

Image 1: The British Foreign and Commonwealth Office via Flickr

Image 2: Atul Loke/Bloomberg via Getty Images