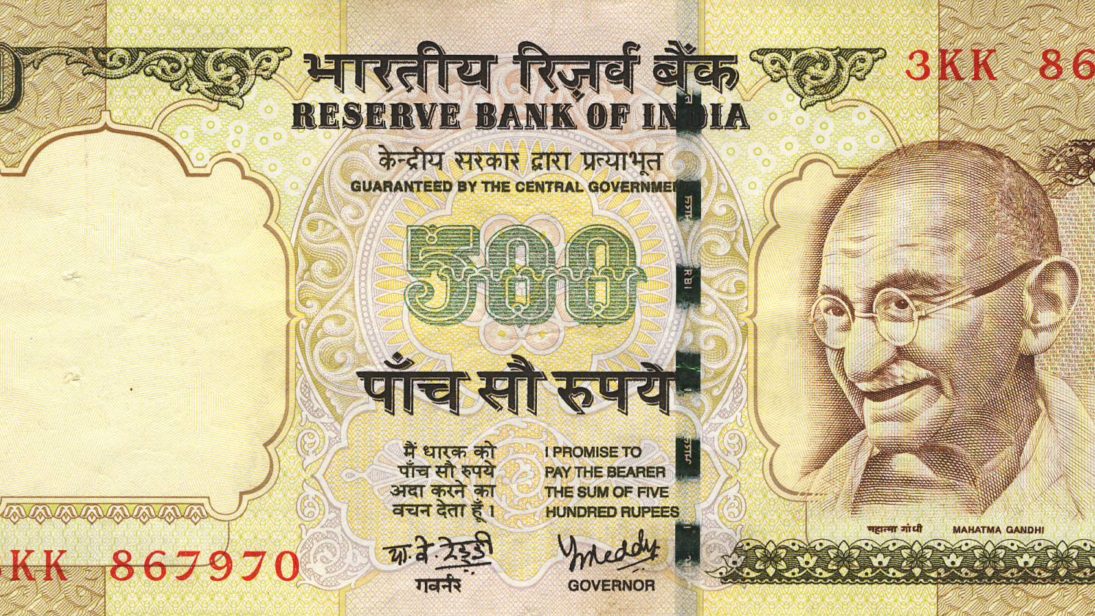

This week, Prime Minister Narendra Modi shocked the nation with his announcement to ban Rs.500 and Rs.1000 currency notes. Demonetization in basic economics is defined as halting a currency unit from being used as legal tender or a medium of exchange. The practice has been used by central banks and national governments to either change the circulation of a given national currency or replace an existing unit with another one. Modi’s attempt has largely been aimed at combating the creation and circulation of illegal wealth in India’s rapidly swelling informal economy, to further check corruption. But will it work?

History Repeats Itself?

In India’s modern economic history, there have been two previous attempts to demonetize existing currency units. The first was when Rs. 5000, Rs. 10000, and Rs. 1000 notes were taken out of circulation in January 1946 to reduce the use of higher currency denominated units. All three denominations were, however, reintroduced for circulation in 1954. The second was in 1978 when the Moraji Desai-led Janata Party coalition used the High Denomination Bank Notes Act to declare these three denominations illegal.

One of the key differences between the current demonetization announcement and earlier attempts lies in the support received by the government from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). I.G. Patel, the RBI governor in 1978, had criticized the move as it was perceived as targeting the “corrupt predecessor government or government leaders.” However, this time around, the current RBI Governor, Urjit Patel has backed Modi government’s demonetization move while acknowledging the “growing menace of fake Indian currency notes” that further exacerbates creation and circulation of illegal money.

Benefits of Demonetization

Economist Ajit Ranade has rightly argued that large denomination notes are “the preferred mode of moving illegal money” and not really used by “ordinary folk.” This is because currency notes with high denominations are rarely used on a day-to-day basis, and ultimately serve the interests of money launders, real estate players, or other tax evaders.

One of the other likely advantages of demonetization can be with respect to increasing the level of bank deposits (with people in thousands coming to declare black money held with them in form of currency notes of Rs. 500 and Rs. 1000). The process may allow banks to significantly boost their household deposits, allowing them a higher capital base (useful in further increasing lending and credit).

Administrative Challenges

However, the actual administrative challenges of creating and printing new denominations would be immense. The share of Rs.1000 notes in the stock of currency circulation is as high as 39 percent of total currency stock (as per 2014-15 figures) and Rs.500 notes account for 45 percent of the total stock. Combined, they account for over 86 percent of all currency notes in circulation. Thus, as these two denominations go out of money stock, the demand for currency notes with smaller denominations (Rs.10, Rs.20, Rs.50, Rs.100) will scale up severely, and may have a significant cost.

According to Livemint’s analysis of RBI data, printing a Rs. 10 note costs 9.6 percent of face value as compared to only 0.32 percent for a Rs. 1000 note. Thus, the RBI would incur higher total cost as it would have to print more smaller denomination notes (Rs.10, Rs.20, Rs.50, Rs.100, Rs. 500).

Additionally, for those with a history of paying taxes diligently, demonetization is likely to be an administrative nightmare, especially banks. They may find it extremely difficult to cope with the pressure of handling long queues as people exchange older currency notes for newer ones. While this may seem to be a temporary problem for administering a currency reform change, it is hard to imagine if the attempted demonetization move to combat generation of illegal wealth will actually lead to the desired result—unless persistent, ancillary measures to curb corruption or illegal wealth are not followed.

Combating Corruption

Deconstructing the basic essence of corruption as a crime of calculation, in a simple yet powerful formula by Robert Klitgaard, corruption equals monopoly plus discretion, minus accountability (i.e. C=M+D-A). And wherever these conditions shall continue to exist (whether in the public sector or private sector), corruption, including the circulation of illegal wealth, shall continue to exist.

The institutional solution for corruption in India lies in going beyond demonetization reform. This would have to include promoting reforms with respect to demonopolization across sectors (such as by creating a more free and easier entry for other firms in a given sectoral market); eliminating human discretion by ensuring the filing of e-returns for income tax; conducting automatic assessments and sending tax refunds to assesse bank accounts; and ensuring financial accountability through effective income declaration methods and widening the tax base. Moreover, efforts would need to be taken to curb conversion of existing piles of black money into gold jewelry by increasing duties on gold imports.

India is one of the most cash intensive economies in the world with a cash-to-Gross Domestic Product ratio of around 12 percent, which is almost four times higher than other emerging economies. For a widely-spread and populated rural India where access to digital payment instruments and banking services are limited, a radical switch to electronic payment systems or plastic money (as a result of demonetization) seems unrealistic (even after taking into account the Modi government’s recent financial inclusion scheme). Thus, persistent efforts will be required to ensure adequate disclosure of unaccounted wealth.

Having said that, the immediate advantage of such a currency reform can be seen with respect to the problem of using cash to fund polls, attached with political parties in times of election season, where more cash is distributed as a medium of exchange. This is likely to be brought under check through the current reform. The Modi shock may have a significant impact on the Uttar Pradesh elections (due in early 2017) where the frequency and density of cash transactions is far more than other states in India (owing to its large unbanked, informal market base).

Concluding Thoughts

Demonetization currency reform by the Modi government is a bold, welcome move. But it will require consistent efforts on part of both the government and the central bank to ensure its efficacy in combating black money and corruption.

***

Image 1: Miran Rijavec, Flickr

Image 2: Narendra Modi, Flickr