The ensuing India-Pakistan crisis in the aftermath of the Pahalgam attack has once again put the fragile architecture of regional stability under stress. The sweeping retaliatory measures by both India and Pakistan have resulted in an unprecedented suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty and Islamabad announcing it “shall exercise the right to hold all bilateral agreements with India…including but not limited to Simla Agreement in abeyance.” This phrase—“including but not limited to”—has introduced a layer of strategic ambiguity in an already murky situation. It is unclear whether these bilateral agreements include nuclear confidence measures (NCBMs), or if those agreements would continue to function. This ambiguity is neither accidental nor irrelevant. At a moment of heightened tensions, this deliberate lack of clarity allows space for future calibration, but it also generates uncertainty about whether some of the most crucial mechanisms underpinning strategic stability in South Asia are still operational.

Why NCBMs Matter

Historically, NCBMs between India and Pakistan have survived difficult periods. Measures such as the annual exchange of the lists of nuclear facilities and prenotification of ballistic missile tests have continued to be implemented through past crises, from Kargil in 1999 and the 2001-2002 standoff to the Pulwama-Balakot crisis in 2019. In this continuity, the two states appeared to affirm that even limited and largely symbolic risk reduction measures held value. These CBMs may have appeared routine or even performative in peacetime, but their real utility becomes clear in times of heightened tension. Their suspension would not simply be symbolic; it would mark a shift toward greater unpredictability.

[…] [T]he hotline is like a fire extinguisher: its value lies in its availability during an emergency, not its everyday use. Suspending it may not have affected past crises, but if suspended now, it would eliminate a potentially vital tool just when the probability of needing it is rising.

If the existing NCBMs are held in abeyance and suspended without formal acknowledgment, the implications are serious. The most critical of these measures are those that are designed to prevent misinterpretation, allow real-time communication, and reduce the risks of accidental escalation and these are precisely the ones at risk of erosion or neglect amid the current diplomatic freeze. For instance, suspension of the nuclear non-attack agreement would reintroduce strategic opacity where clarity, however minimal, is desperately needed. Additionally, the ballistic missile prenotification agreement serves a vital purpose in reducing the risk of misreading a test as a strike, especially in a region where strategic warning time is minimal, and rapid decisionmaking could quickly lead to catastrophe. Discontinuation of this agreement would increase the potential for misinterpretation, implying that the margin for miscalculation has shrunk dangerously. This is especially so because such a misunderstanding would unfold against the backdrop of the 2022 BrahMos missile misfire incident. That incident occurred during peacetime and did not turn into a crisis, but a similar episode in the context of a full-blown crisis would trigger a profoundly different response.

The crisis hotline offers a direct channel between senior civilian officials to resolve misunderstandings at moments when backchannel diplomacy and third-party mediation may not be fast enough or feasible to prevent escalation. Yet, despite its importance, the hotline has never been used in an actual crisis between India and Pakistan. This persistent underutilization raises questions about political will and institutional readiness on both sides to use existing tools for de-escalation.

Because the hotline has never been used, its suspension can have two potential effects. First, the practical impact may appear minimal at face value. If a mechanism has remained dormant through multiple crises, its absence may not immediately change how states behave. However, this underestimates the importance of institutionalizing pathways for communication, especially in the nuclear realm. Mechanisms like hotlines are not created to be used daily. They exist for exceptional circumstances, when miscalculation, confusion, or misinterpretation can lead to unintended escalation. In that sense, the hotline is like a fire extinguisher: its value lies in its availability during an emergency, not its everyday use. Suspending it may not have affected past crises, but if suspended now, it would eliminate a potentially vital tool just when the probability of needing it is rising.

Second, suspending even unused or symbolic agreements depicts a deeper degradation of bilateral trust and the erosion of even the most basic channels of nuclear risk management. That Pakistan and India have not signed a single new NCBM in 18 years—and that there has been no structured nuclear dialogue for over a decade—underscores how little political capital exists for even minimal cooperation. In this context, the formal suspension of the hotline agreement would not merely confirm its dormancy; rather it would institutionalize absence, harden positions, and signal that both states are prepared to navigate the current crisis without guardrails.

The Subcontinent’s Unraveling Strategic Stability

The structural deficiencies in the nuclear CBMs regime between India and Pakistan become even more conspicuous and worrisome in times like these. Here, one of the most important challenges is the erosion of political will. If India and Pakistan no longer perceive nuclear CBMs as valuable trust-building mechanisms, implementation becomes inconsistent, and eventually, inconsequential. This opens the door to gradual disengagement from bilateral obligations and normalizes the reversibility of agreements. India’s suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty and Pakistan’s announcement that it reserves the right to place bilateral agreements such as the Simla Accord in abeyance reflects this shift. While these are conditional postures rather than an outright withdrawal, these developments are concerning because of the ease with which these longstanding frameworks are suspended with minimal domestic backlash or international costs.

The current India-Pakistan crisis is a test of whether even the thinnest threads of restraint can hold between the two states. The ambiguity surrounding the status of nuclear CBMs is not just a bureaucratic oversight; rather it raises the larger question of whether both states are still invested in the idea of risk reduction—especially as both are modernizing their nuclear arsenals, both qualitatively and quantitively. Amid this escalation, Pakistan’s issuance of a Notice to Airmen for April 24 and 25 indicating an impending missile test in the Arabian Sea signaled procedural adherence to the agreement on prenotification of ballistic missile tests. At the time of this writing, the test has not been conducted. Still, the notification suggests that risk-reduction norms serve a purpose. They may not prevent war, but they provide vital space for misperceptions to be corrected and escalation to be managed. Their absence would remove that margin for error.

The current India-Pakistan crisis is a test of whether even the thinnest threads of restraint can hold between the two states. […] In a region where crises emerge quickly and escalation timelines are compressed, the absence of even minimal engagement in the form of the implementation of nuclear CBMs can prove catastrophic.

As both India and Pakistan confront a potentially prolonged period of antagonism, the consequences of allowing nuclear CBMs to lapse, either formally or informally, could be severe. The stakes are not theoretical. In a region where crises emerge quickly and escalation timelines are compressed, the absence of even minimal engagement in the form of the implementation of nuclear CBMs can prove catastrophic. At present, it appears that the future of South Asian stability may depend not on grand agreements or breakthrough diplomacy, but on whether the most basic guardrails are quietly allowed to disappear.

Views expressed are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the positions of South Asian Voices, the Stimson Center, or our supporters.

Also Read: Why the Kashmir Attack Could Start Another India-Pakistan Crisis. For more analysis on Pahalgam and its aftermath, read our entire series here.

***

Image 1: India-Pakistan Flags via Wikimedia Commons

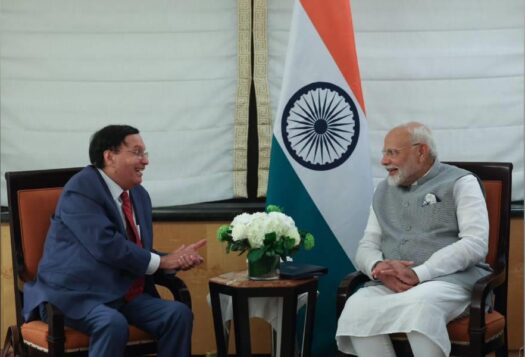

Image 2: Pakistan Inter Services Public Relations via Anadolu Agency/Getty Images