In a recent announcement, the Pakistani government declared that 1.7 million undocumented Afghan migrants must leave the country by November 1st either voluntarily or by force. South Asian Voices Deputy Editor Mahika Khosla and Associate Editor Sania Shahid spoke with Noorulain Naseem about the humanitarian, security, and diplomatic implications of this move. Noorulain is a Research Associate with the Islamabad Policy Research Institute (IPRI) and a former Visiting Fellow at the Stimson Center. Her policy and academic research focuses on Pak-Afghan border security, Afghan refugees and the spillover of Afghan conflict in Pakistan.

What are the factors that led the government to take this drastic move?

The justification given by the government for the decision was a rapid increase in terrorist activities in KP and Baluchistan by 59 percent and 39 percent respectively in 2023. This, however, is not the first time that Pakistan has securitized the Pak-Afghan border. In 2021, the government fenced the 1615-mile terrain, and in 2014, crafted Pakistan’s National Action Plan which included a clear policy on registering Afghans residing in Pakistan.

The interim government’s recent decision is meant to encompass ‘all illegal migrants residing in Pakistan’, focusing on those who have forged IDs and are involved in drug trafficking, smuggling, and the exchange of illegal finances across the border. The Apex Committee headed by the caretaker Prime Minister of Pakistan, based its decision on a few challenges. First is the heightened threat perception of Pakistan’s security sector against the TTP and ISK, which includes their cross-border movement to conduct hit-and-run operations, seek hideouts in Afghanistan, and sustain finances via illegal trade and crime across the Pak-Afghan border. Second is Pakistan’s desire to become a transit and trade hub for South Asia under BRI projects. This requires internal and border security, as well as strict monitoring of border transit points across Baluchistan and KP since these regions share a border with trading partners like Iran, Afghanistan, and China.

The committee designed a strict transit policy where after 1st November 2023, entry would be based on the possession of a valid visa and Afghan passport, whereas previously, only a Tazkira (Afghan ID), Proof of Registration Card (PoR) or even Prima Facie based entry for refugees was possible across the border.

Unfortunately, stringent border control curtails the refugee movement as well. After the 2021 takeover of Kabul by the Taliban, Pakistan received around 700,000 Afghans. Pakistani authorities have repeatedly vocalized the government’s incapacity to sustain refugees since the country’s economic crisis and political instability are already tolling on the governance and welfare of Pakistani citizens.

Given these factors, the committee designed a strict transit policy where after 1st November 2023, entry would be based on the possession of a valid visa and Afghan passport, whereas previously, only a Tazkira (Afghan ID), Proof of Registration Card (PoR) or even Prima Facie based entry for refugees was possible across the border.

The Pakistani government has said that 14 out of 24 terrorist attacks in Pakistan this year were carried out by Afghan nationals. What is your assessment of this claim?

Pakistan’s proximity to Afghanistan results in the spillover of some violence from across the border. In September 2023, the Afghan interim government confirmed capturing 200 TTP fighters from Afghanistan. These fighters were involved in attacks against security forces in the Chitral region of Pakistan, earlier that month.

In a recent policy memo I published as a Visiting Fellow at Stimson, I highlighted the risks associated with the unmanaged transit of people and goods across the Pak-Afghan border. The porous nature of the border allows illegal migrants, crime, and terror to cross country lines. The border terrain is regularly used by Pashtun tribes who are divided across the terrain, and increasingly so by women and ethnic minorities who are adversely affected by the Afghan Taliban’s policies. The Pakistan government and TTP held peace talks in 2021, negotiating the return of former TTP fighters and their families on disarmament conditions. The talks were unsuccessful but were perceived as a green signal by TTP fighters in Afghanistan to start relocating to Pakistan. They reportedly crossed the border and revived the otherwise disjointed terrorist offshoots alive in border terrain despite repeated military operations by Pakistan. This has been a factor in enabling dubious actors and networks to sustain operations.

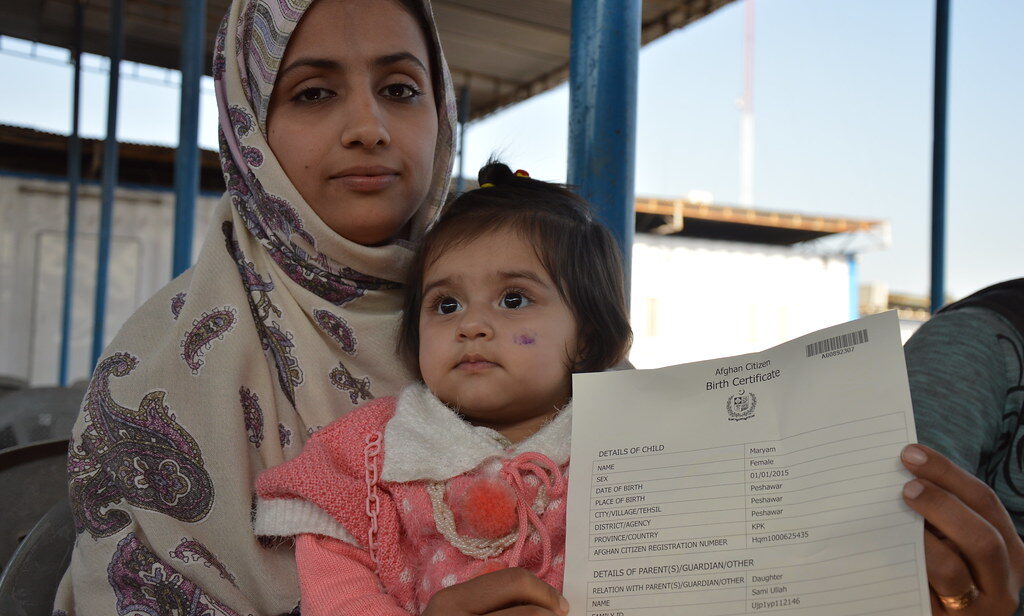

While the Apex Committee’s decision intends to curtail transnational crime and terror, it will arbitrarily affect Afghan refugees and economic migrants as well. The lack of laws on refugees in Pakistan leads to poorly defined migrant categories, making it difficult for transit and border control authorities to differentiate between various forms of migrants upon arrival. As a result, the Apex Committee’s sudden decision to crack down on illegal migrants puts thousands of unregistered Afghans, especially those who arrived after the withdrawal, at risk of detention and prosecution till proven innocent.

The Taliban has responded saying that this move is “unacceptable.” How may this impact Pakistan’s relationship with Afghanistan moving forward?

The Pakistani government’s relations with the Taliban have seen better days. Taliban along with local Pashtun leaders from Jamiat-e-Ulma-Islam (JUI) and Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM), have criticized Pakistan’s decision to deport all Afghans who are illegally residing in Pakistan. Pakistan insists that the lack of cooperation from the Taliban’s border forces pushed it to take such drastic measures. The Torkham border was closed last month after Taliban’s border forces exchanged fire with Pakistani security forces and attempted to build check posts inside Pakistan’s territory. This resulted in huge trade losses for Afghanistan, which is landlocked and is barely sustaining its economy.

Refugees were also barred from entry during that time, which offended Pashtuns in Pakistan since most of them have trading businesses or familial ties across the border. Most Afghans who took refuge in Pakistan after 2021 held moderate views or were ethnic minorities themselves. Cracking down on them will not be received well by moderate factions of the Afghan Taliban, Afghan minorities, and Pashtuns from both sides of the border. People-to-people contact has been a hallmark of bilateral ties between both states that translates into millions of dollars of trade, inter-marriages, education opportunities, and transit route access across Asia and the Indo-Pacific.

Pakistan through an executive order of the Ministry of State and Frontier Regions, directed its security sector to refrain from detaining or prosecuting 1.3 million PoR card holders and 840,000 Afghan Citizen Card (ACC) holders, although these cards expired in June 2023. However, Afghanistan’s diplomatic mission in Pakistan recently stated that around 1,000 Afghans have been detained despite having legal documents of registration. This is a moment of reflection for Taliban whose policies on women’s education, dealings with ethnic minorities, and form of government force Afghans to seek refuge elsewhere with minimal or no documentation, exposing them to prosecution, detention, and deportation. Concrete steps by the Taliban like issuing an official decree (fatwa) against TTP using Afghanistan as a launching pad can normalize relations with border regimes of neighboring states like Pakistan.

International organizations have warned the Pakistani government against the deportation of Afghan nationals. How can we expect the rest of the international community to respond?

Pakistan is not the only state in the region that has securitized its border with Afghanistan. Iran and India, for example, have also denied visas, refused to update them in some cases, and deported illegally settled Afghans since 2021. After the Ukraine-Russia war, international donor interest and investment have been directed away from Afghanistan. In 2023, only 57 percent of the budget needed for UNCHR Pakistan operations was met. INGOs operating in Pakistan like UN agencies are wary of this decision’s impact on vulnerable refugees. Though a major implementing partner of the Pakistan government, the UNHCR cannot act in Pakistan without the government’s permission.

The government should keep negotiating with relevant stakeholders including the Taliban, refugee groups, local communities, INGOs, diplomatic missions on the ground, and donor states, to explore mutually acceptable pathways to systematic repatriation, resettlement to third countries, or gradual integration.

If Pakistan’s crackdown on illegal migrants results in the targeting of innocent Afghan refugees, the situation can cost Pakistan its international goodwill. INGO missions have offered to facilitate access to a wider donor pool, assist in processing asylum requests to third country settlement and they are also extending legal aid to detainees. UNHCR may also reflect on its four-decade presence in Pakistan that could not lead to sustainable solutions for the Afghan refugee crisis. International organizations that are wrapping operations from Afghanistan and donor states that refuse to engage with the Taliban may reconsider the associated costs of isolating the Afghan economy and population.

Pakistan is clearly overwhelmed by the refugee situation but deporting 1.7 million refugees is not only a massive administrative undertaking but also inhumane. What are some recommendations to balance the government’s interests with those of the refugees?

There is much at stake for Pakistan’s government right now: its bilateral relations and trade with Afghanistan, the sentiments of local Pashtuns, international goodwill, donor commitments, and decades of investment in Afghan refugees. Not signing the Geneva Convention has not kept Pakistan from extending protection and integrating more than 68 percent of Afghan migrants into its population. The non-signatory status should not keep Pakistan from crafting procedures to manage migrants and refugees. Consensus-based Parliamentary action in the form of responsive legislation on Afghan refugees, and resulting transparent border and transit control mechanisms can make things easier for Afghan traders, refugees, and Pakistan’s security sector.

The government should keep negotiating with relevant stakeholders including the Taliban, refugee groups, local communities, INGOs, diplomatic missions on the ground, and donor states, to explore mutually acceptable pathways to systematic repatriation, resettlement to third countries, or gradual integration. Stakeholder engagement can help implement the Apex Committee’s decision in a way that does not compromise the integrity and security of millions of Afghans.

Also Read: Two Years After Taliban Takeover: What is India’s Afghanistan Policy?

***

Image 1: Afghan Refugees Holding a Birth Certificate via Flickr.

Image 2: Afghan Border Policeman at the Pak-Afghan Border via NARA & DVIDS Public Domain Archive.