Over the past year, and more so in recent months, Nepal’s ongoing political disorder has put the pandemic and response to natural disasters—including landslides and forest fires—on the backburner. The state government and political leaders have continued to prioritize political gains over addressing the pandemic, with the country witnessing several attempts—some successful—to dissolve the Parliament, alongside potential super-spreader political rallies and overall mismanagement of public health measures.

After an extended period of political unrest, Sher Bahadur Deuba was sworn in as the “new” prime minister for the fifth time on July 13. This marked the end of the rule by the Nepal Communist Party (NCP) government, which initially came to power on promises of “prosperity and stability,” but as of 2021, it has failed to deliver either. With the ongoing turbulence in Nepal’s domestic politics, it is clear that Nepal’s transition into a full democracy remains a challenging process with the diminishing faith of its citizens in its central government.

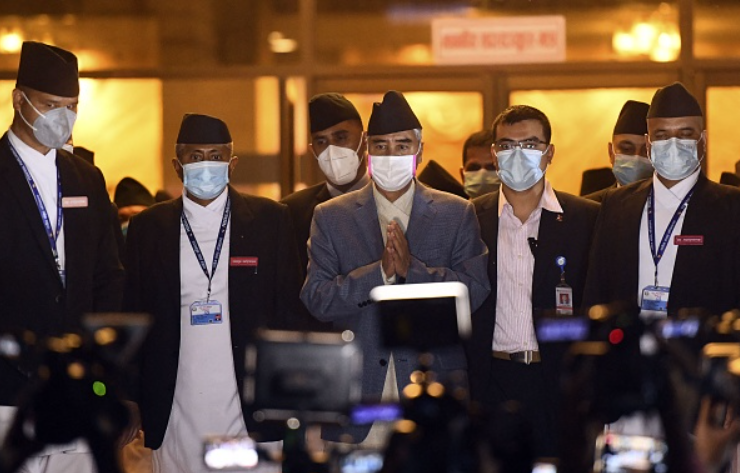

The Chaotic Appointment of Sher Bahadur Deuba

After abolishing the monarchy in 2008, this first general election in Nepal was held almost a decade later in 2017, but political stability remains a distant goal. K.P. Oli’s appointment as Prime Minister in 2018 brought about expectations for socio-economic transformation in Nepal. His second premiership was supported by the strongest government yet, as Oli’s Communist Party of Nepal-Unified Marxist-Leninist (CPN-UML) and Pushpa Kamal Dahal’s Communist Party of Nepal-Maoist Center (CPN-MC) forged an alliance, successfully securing nearly two-thirds of the seats in the 275-member House of Representatives. Under this alliance, the two parties merged to form the NCP, which was ultimately dissolved by the Supreme Court in March 2021, deeming it “illegitimate” over naming issues.

With the ongoing turbulence in Nepal’s domestic politics, it is clear that Nepal’s transition into a full democracy remains a challenging process with the diminishing faith of its citizens in its government.

The alliance rested upon Oli and Dahal taking turns as Prime Minister during the NCP’s five-year term, but a bitter power struggle unfolded between the two instead as Oli refused to relinquish his seat. Internal tension in the party began to escalate during Oli’s second tenure as prime minister. He sidelined his party members in government decisions and appointments, motivating Dahal and Madhav Kumar Nepal to create an opposition alliance in December 2020. The dissolution of the NCP in 2021 reverted Oli and Dahal back to their pre-merger positions of Chairmen of the two constituent parties, CPN-UML and CPN-MC.

With his own party members questioning his motives, Oli resorted to the dissolution of the Parliament in December 2020. However, on February 23, 2021, the Supreme Court ruled the move unconstitutional, reinstating the Parliament. The rivalry between the Dahal-Nepal and Oli factions surged as supporters took to the streets to protest amidst the pandemic in February with thousands of people demonstrating their support both for and against Oli in separate rallies. The situation came to a head in May 2021 where Oli lost the vote of confidence in the House of Representatives. Consequently, President Bidya Devi Bhandari announced a 72-hour deadline to form a coalition government with a majority in the House. The failure of the opposition parties to form a new coalition government by the deadline led to the reappointment of Oli, as chairman of CPN-UML which maintains the majority in the House of Representatives.

According to the constitution, Oli needed to obtain another vote of confidence, but Oli instead recommended President Bhandari to invoke Article 76(5), which allows any parliamentary member who is able to showcase the ability to win a vote of confidence to be appointed as Prime Minister. As per this article, Sher Bahadur Deuba, President of the opposition Nepali Congress party, showcased signatory support from 149 members while Oli claimed to have support from 153 members. President Bhandari rejected both their claims, and as per Oli’s recommendation, dissolved the Parliament for the second time.

On July 12, the Supreme Court stepped in once again declaring Deuba’s claim of adequate signatory support to be constitutional, ordering the reinstatement of the House of Parliament and the appointment of Deuba as the new Prime Minister. On July 18, Deuba secured a vote of confidence with 165 votes on the first day of the House session. In accordance with Article 76(6) of Nepal’s constitution, Deuba will serve as Prime Minister for 18 months, which is when the next periodic election is scheduled.

Politics over Pandemic

The current political upheaval has unfolded in the background of the global coronavirus pandemic, devastating natural disasters, and civil unrest. As of July 27, Nepal reports 28,836 active COVID-19 cases. As experts warn of an impending third wave, the next few months of Deuba’s tenure remain crucial for his government to procure enough vaccines for the country and bolster the national vaccination drive. Deuba has reassured the nation that: “[Nepal] will bring vaccines [into the nation] no matter how expensive they are.” With the World Bank already providing Nepal with USD $100 million and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) approving a loan of USD $165 million for the purchase of vaccines, Deuba must ensure transparency in their procurement and distribution.

Nepal has had five Health Ministers in the past three years, four of which were appointed during the pandemic by the Oli administration. While Deuba seems to be focusing on tackling the pandemic so far, he was criticized for taking two weeks to appoint a health minister, which should be of the highest priority as COVID-19 cases rise again. Deuba’s government has pledged to vaccinate one-third of Nepal’s citizens in the next three months. Only 12 percent of the population has recieved at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, but an influx of bought and donated vaccines has reignited the inoculation drive.

Vaccine Distribution: Challenges Ahead

Globally, Nepalese people are some of the most willing to get vaccinated; the biggest hurdle in inoculating the country is the accessibility to the vaccines. As Nepal begins to get back on track for meeting demands for vaccine finances and supply, Deuba’s biggest task is improving vaccine accessibility, through a more systematic vaccine drive, updating online registrations, coordinating amongst provinces, and distributing information. Deuba also must work towards providing authentic vaccine certification and ensure that Nepal’s paper-based vaccine documents that are being provided will be valid globally. Another major hurdle is the storage of vaccines—while millions of vaccines are set to be shipped to the country, Nepal’s central city Kathmandu can only store one million vaccines.

Already prone to natural disasters, the dual challenges of a global pandemic and extreme weather in the past year underscore the security threats Nepal is likely to face for years to come.

Vaccinations have also been highly skewed towards urban centers, namely Kathmandu. Along with geographical challenges, systemic, social and economic inequalities that persist in the country prevent fair access to healthcare. The disparity between urban-rural and regional areas in healthcare and transport infrastructure has hampered national distribution including to vulnerable populations such as the elderly and migrant workers. As of the beginning of July, approximately 1.4 million elderly Nepalese above the age of 65 that had received the first dose of AstraZeneca in March are yet to receive their second dose. The incoming government will also be tasked overseeing the distribution of the 1.5 million doses of Johnson & Johnson vaccines received from the United States to migrant workers as it has promised. Many migrant workers had previously been administered VeroCell developed by Sinopharm, which was not approved by many destination countries. However, the low numbers of Johnson & Johnson vaccines means that the government may need to switch back to VeroCell, which could further hurt Nepal’s economy which relies heavily on remittances.

Addressing the Future National Security Landscape

Beyond the pandemic and its associated economic fallout, Nepal experienced its worst wildfire season during the second wave of the pandemic and is facing catastrophic floods and landslides accompanied by fears of a looming third wave of COVID-19. Already prone to natural disasters, the dual challenges of a global pandemic and extreme weather in the past year underscore the security threats Nepal is likely to face for years to come. As non-traditional security threats like pandemics and climate change disproportionately threaten vulnerable populations and amplify existing inequalities across the globe, Nepal’s leadership will need to place long-term mitigation and preparation to these intersectional threats in the forefront instead of political feuds.

The road ahead will not be easy for Nepal as it struggles to envision the post-pandemic scenario. Historically, Nepal has been a hotbed of political turmoil for decades, every government since 1990 having succumbed to political power struggles. With likely political friction ahead alongside the needs to address vaccination procurement, distribution challenges, and the increasing impact of natural disasters, Nepal requires a government to showcase strong leadership by putting Nepalese people before politics more than ever. The new government has the chance to regain the faith of its citizens by showcasing a commitment to improving the response to COVID-19 and working cohesively to strengthen democracy in Nepal.

***

Image 1: PRAKASH MATHEMA / AFP via Getty

Image 2: PRAKASH MATHEMA/AFP via Getty Images