Content warning: this essay contains references to domestic and sexual abuse.

Research informing this article was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

In recent years, Pakistan has introduced and passed various bills to safeguard the rights and protection of domestic workers in the country, including the Islamabad Domestic Workers’ Bill 2021, the Punjab Domestic Workers Act 2019, and the Sindh Home-Based Workers Bill 2022. Workers and activists have welcomed such bills as a step in the right direction. The country’s “informal” workforce has long faced severe exploitation and dehumanization without much intervention from the state.

Changing social norms, employers’ expectations, and devoting more resources to implementing existing laws can better protect Pakistan’s domestic workers in the future.

However, looking beyond the passage of these bills, the reality on the ground has largely remained unchanged. Most of the promises made by lawmakers in these bills—from creating contracts for workers, standardizing minimum wages, and establishing a force of inspectors—have yet to materialize, despite increasing reports of exploitation and mistreatment of domestic workers across the country. Changing social norms, employers’ expectations, and devoting more resources to implementing existing laws can better protect Pakistan’s domestic workers in the future.

The Issue

While no consolidated official statistics are available, the International Labor Organization (ILO) estimated that there were at least 8.5 million domestic workers in Pakistan in 2015. The number is likely much higher, considering the difficulty of accounting for informal labor in the private sphere. Widely referred to as “maids,” consisting primarily of women and young girls, these workers are employed informally across middle and upper-middle-class households to carry out domestic chores like cleaning, washing, and babysitting. Many of these workers have been doing these tasks for years and have become proficient at their job, yet they are widely considered unskilled labor and are not guaranteed the same rights and protections the formal workforce enjoys.

The exploitation of domestic workers goes beyond a lack of workers’ rights. Employers often mistreat their domestic workforce. Young workers have been beaten for minor mistakes. Some households “separate” their domestic workers’ eating utensils so they do not mix with the family’s dishes. Nannies or “ayahs” are sometimes made to sit apart from the family if they go out to eat. Verbal, financial, and sexual abuse is widely prevalent.

Most such cases go unreported due to fear of retribution. However, some prominent cases have garnered media attention in recent times. In 2020, an eight-year-old worker named Zahra Shah was beaten to death by her employers in Rawalpindi after she let their pet parrots free. In 2016, a 10-year-old girl named Tayyaba was found to have been repeatedly tortured by her employers, with severe bruises around her face and hands.

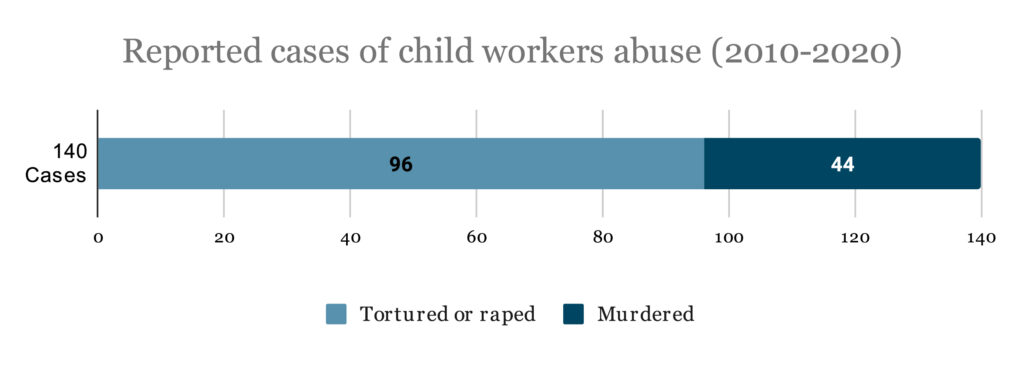

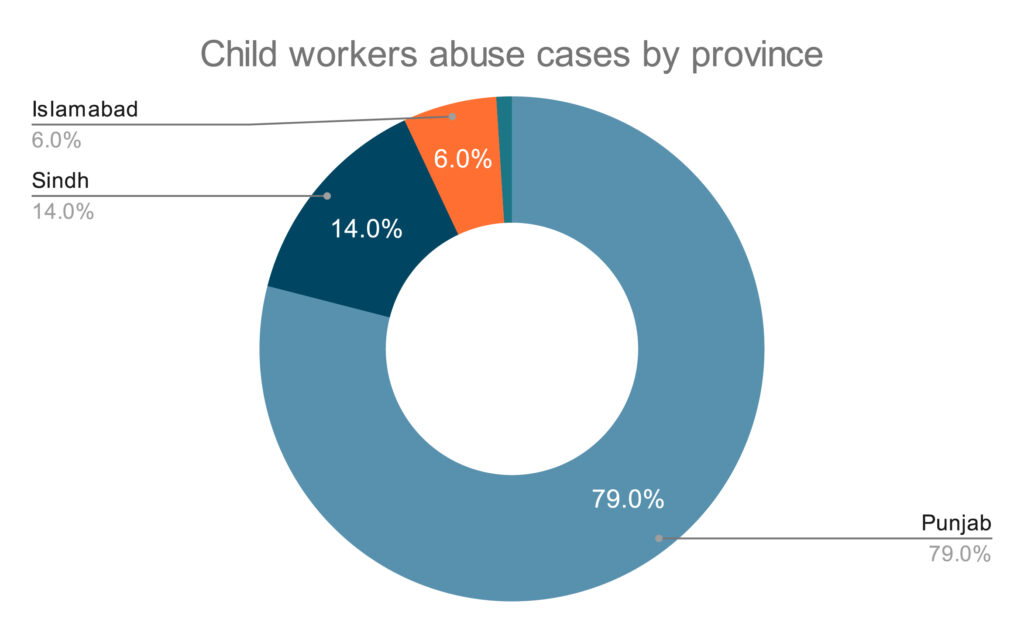

Source: Hari Welfare Association (HWA), the Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (Piler) and the Institute for Social Justice (ISJ)

In 2019, Punjab passed the Punjab Domestic Workers Act, bringing these workers under the protection of official labor laws. Last year, the federal capital passed the Islamabad Domestic Workers Bill 2022, setting standards for on-time payment, minimum wage, working hours and holidays, etc. The bill aimed to formalize the largely informal sector of domestic workers and create regulations and policies for protecting domestic workers’ rights.

Punjab had also pledged to register all domestic workers through its social welfare platform Punjab Employees Social Security Institution (PESSI), but by 2021, it had only registered 14,717 workers. The registration system remains open on the PESSI website and mobile app. Still, the low registration numbers—considering the more than 8.5 million estimated by the ILO—reflect that improving the conditions of these workers would take more than passing laws or creating registration portals.

Challenges Ahead

If these laws are to be put to good use, authorities need to create widespread awareness about them among domestic workers and employers. Government entities like the Ministry of Labor and Workers’ Welfare Fund should aid such initiatives nationally.

Several domestic workers the author talked to in Punjab did not know about the Domestic Workers Act or that they have a right to the minimum wage. One worker said the introduction of contracts or minimum wage would only limit her employment opportunities as their profession is not ready for such legal restrictions. Asking employers and employees to sign contracts or make monthly payments through banking channels would introduce new hurdles for the largely uneducated workers, who would need further training to navigate such avenues.

These fears have been echoed by other domestic workers, who are cautious of raising their voices or demanding their legal rights because of the abundance of other laborers willing to take their place for less pay. Unregulated termination and employment practices result in workers being asked to leave without cause or notice, but at the same time provides workers with the option to leave their place of employment if a better offer comes along. Convincing both sides to bind themselves in a legal contract would be challenging.

Even if the domestic workers agree to registration and contractual work, more effort would be needed to onboard the employers. This profession thrives because of the ease with which employers can find workers at low wages, especially when recruiting child domestic workers.

Dr. Ghazal Mir Zulfiqar, an academic researching poverty and rural development who has extensively researched domestic workers, told the author in an interview that employers are not ready for this change. “I blame the people who thought that passing a bill and steamrolling it onto us will solve anything because it cannot,” she said. “You have to make the public ready for it. We would need to run cultural campaigns because culture and public policy go hand in hand.”

The institutionalized and internalized issues are rooted in myriad problems, including Pakistan’s ever-increasing population in a country where unemployment is rising, child labor is easily available and unregulated, and attitudes towards labor laws are lax and inconsistent at the very least. There is a marked class difference that seeps into mindsets, creating a clear divide between workers and employers.

In 2015, Pakistan established the Domestic Workers Union, the first of its kind in the country. While the union only has a few hundred members so far (its existence is unknown to most workers), existing laws provide good legal ground for the organization to create awareness and campaign for better working conditions.

The institutionalized and internalized issues are rooted in myriad problems, including Pakistan’s ever-increasing population in a country where unemployment is rising, child labor is easily available and unregulated, and attitudes towards labor laws are lax and inconsistent at the very least.

To create any positive and widespread impact, the union and other stakeholders would need to work both at macro and micro levels, including challenging social norms, changing mindsets and the expectations of employers, and pushing the government for more resources toward implementing these laws. Attaining these feats would require a cultural shift in social attitudes beyond what mere laws and policies can influence. Perhaps the plight of domestic workers can become an integral part of widespread rights campaigns in the country like the Aurat March. Moreover, the educated elite — academics, politicians, activists, etc. — who commonly employ domestic workers can advocate for their rights with as much rigor as they do for other social causes.

***

Image 1: Яah33l via Wikimedia Commons

Image 2: Power22 via Wikimedia Commons