On Feb. 14, 2019, a suicide bomber from the Islamist terrorist group, Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM), attacked a Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) caravan, resulting in one of the deadliest attacks on Indian security forces in Kashmir. As JeM is a Pakistan-based militant organization with extensive ties to the Pakistani military establishment, India attempted to bomb a JeM training camp in Balakot, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. The attack and its aftermath led to yet another standoff between the two nuclear powers.

Although the Balakot airstrikes were a significant break from past operations against militancy, India has long struggled with state-sponsored terrorism emanating from Pakistan. This has resulted in numerous commentaries on how India might deter Pakistan and motivate it to crack down on terrorism.

Perhaps serendipitously, Wendy Pearlman and Boaz Atzili’s latest book, Triadic Coercion (Columbia University Press, 2018), addresses the very problem of compelling states to crack down on militant organizations. Through the lens of Israel’s experience in fighting terrorism, Pearlman and Atzili’s book has significant theoretical implications for India’s case of fighting state-sponsored terrorism, which is briefly examined in the book. The authors caution that a more comprehensive investigation on India’s situation is needed to verify their findings. By applying their model of triadic coercion to India’s counterterrorism approach in Bhutan and Pakistan, this article reaffirms the significance of host regime strength in combating militant groups.

Triadic Coercion

Triadic coercion is defined as a situation in which one state uses military threats and/or punishment against another state to deter it from aiding or abetting attacks by non-state actors from within its territory, or when it compels the state to stop such violence. For instance, President Bush’s attempt to coerce the Taliban government in Afghanistan to crack down on al-Qaeda following the September 11th attacks is an example of this form of compellence.

Pearlman and Atzili’s argument centers on a question: under what conditions does triadic coercion succeed? The authors find that triadic coercion is most likely to succeed when a targeted regime is in a position of strength. Strength is measured by a state’s institutional competency, domestic political legitimacy, and territorial control. Although the regime’s “cooperative” (predisposed to aiding the coercer) or “defiant” (uncooperative) nature towards the coercer may determine the coercer’s approach, targeted regime strength is the overriding determinant for successful triadic coercion. This brings Pearlman and Atzili to their second major puzzle and subsequent contribution: why do states continue triadic coercive policies if conducive conditions are not present?

Although the regime’s “cooperative” (predisposed to aiding the coercer) or “defiant” (uncooperative) nature towards the coercer may determine the coercer’s approach, targeted regime strength is the overriding determinant for successful triadic coercion.

To answer this, the authors put forth a new explanation for states’ engagement in triadic coercion–they are not necessarily guided by strategic calculations as much as by a strategic culture. Strategic culture, manifest in decisionmaking and ideas, is grounded more in socially constructed norms and identities than in interests. An analysis of strategic culture, they argue, allows analysts to understand why states undertake aggressive or defensive actions, even when such an action may be counterproductive.

To gauge vigor and applicability of Pearlman and Atzili’s triadic coercion theory, I analyzed two other coercive episodes between India-Bhutan and India-Pakistan. These cases provide further empirical evidence on the importance of regime strength while simultaneously illustrating India’s differing approaches toward a “cooperative” Bhutan compared to a “defiant” Pakistan. As the authors argue, regime strength triumphs every time in determining the success of triadic coercion.

Operation All Clear

The case of India’s coercion of Bhutan to act against militants in the Northeast in the early 2000s is evidence of successful triadic coercion in the context of a strong, cooperative regime. During the 1990s, Indian counterinsurgency operations in the Northeast forced the leadership of the United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA) and National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB) to migrate to other countries. These groups relocated to Bhutan, and the Bhutanese government decided to ignore these groups since they did not pose a direct threat to the state. Even if they desired action against the groups, it was questionable if the Bhutanese government was militarily powerful enough to force the insurgents out. Of course, this did not sit well with India, since the insurgents were now able to strike India from their new safe haven.

From 1999 onward, Bhutan’s view of the insurgents changed. India made it clear that it viewed the presence of these groups as unacceptable, and the militants began to pose a threat to Bhutanese political stability. On December 15th, 2003, the Bhutanese government initiated Operation All Clear, the country’s first military operation in 140 years, to oust these organizations. With logistical and medical assistance from the Indian military, Bhutan was successful in removing the anti-India insurgents.

Although India did not directly coerce Bhutan through military action or economic sanctions, India did apply diplomatic pressure and claimed that these groups posed a threat to the India-Bhutan relationship. Their strong historical relationship as well as the significance of India to Bhutan’s economy made the regime predisposed to cooperate. This, combined with the possibility of unilateral Indian action, played a role in Bhutan’s decision to launch the operation.

By the time Operation All Clear was launched, the Bhutanese regime was strong enough to fight the insurgents. The royal government in Bhutan built political resolve to attack the insurgents and strengthened its military. In a similar vein, India did not undertake any actions that would have undermined the Bhutanese king politically or weakened the country’s capacity. In fact, India trained and aided the Royal Bhutanese Army during military operations, and exercised strategic restraint to support the Bhutanese government rather than attempt unilateral action. By having a strong Bhutanese regime, India was able to coerce its neighbor to act against non-state actors. Although Bhutan was cooperative, any early action by India would have undermined the political standing of the Bhutanese government, ultimately harming India’s goals.

The Khalistan Insurgency

India’s coercive approach toward the Pakistani state during the Khalistan insurgency supports the argument for successful triadic coercion vis-a-vis a strong yet defiant regime. Between the 1980s and early 1990s, India faced a Sikh separatist movement in its northern state of Punjab. The insurgency had some support from Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). In retaliation, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi directed India’s external intelligence agency, the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), to form two counterintelligence teams to conduct covert action in Pakistan in the mid-1980s– one to attack general targets in Pakistan and one to directly hit Khalistani organizations. This campaign saw some success, as the heads of the ISI and RAW agreed to cease covert attacks in Indian Punjab and Pakistan respectively.

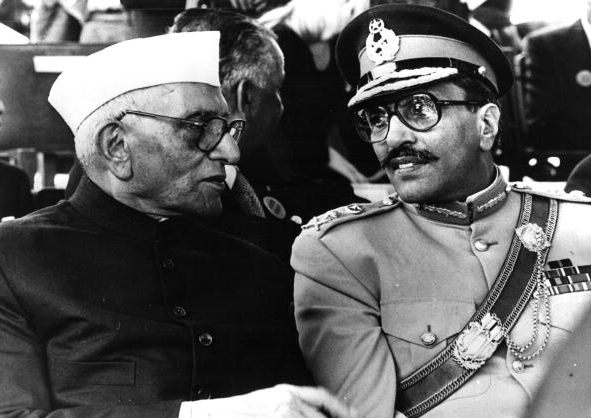

During the insurgency, Pakistan was ruled by the military dictator, General Zia-ul-Haq. Pakistan’s support for the Khalistan movement coincided with the United States and Saudi Arabia funneling large amounts of money to the country for hosting and supporting the mujahideen in Afghanistan. Despite some domestic opposition, Zia had tight control over the country, with a declassified CIA study observing that his opposition was disorganized and the military remained firmly behind the military dictator. This economic support combined with Zia’s tight control of the state suggests that Pakistan under the Zia regime was a strong one, one powerful enough to act against militants if it so pleased.

While refraining from military force, India took a different course of aggressive action to deal with a “defiant” strong Pakistan. This contrasts with Pearlman and Atzili’s case study where India’s coercion in 2001 and 2008 failed because the Pakistani regime was weak. As the authors pointed out, elements of the Pakistani regime, such as its intelligence agencies, continued to aid the militants as the state banned it. Their case study differs from Zia’s regime where he faced little domestic opposition and had powerful international support. Thus, India’s coercion against Zia’s Pakistan worked despite its defiant outlook, confirming the importance of regime strength in achieving triadic coercion success.

Conclusion

Although undertaking military action to coerce a state might feel empowering, it accomplishes little if the targeted regime is weak.

Pearlman and Atzili’s book is a valuable scholarly contribution in understanding triadic coercion. As demonstrated above, applying their model to India’s experiences confirms their central argument that emphasizes host regime strength. Although undertaking military action to coerce a state might feel empowering, it accomplishes little if the targeted regime is weak. It would be wise for policymakers and analysts to pick up a copy of Triadic Coercion to learn what conditions are necessary for deterring state-sponsored terrorism, and what are self-defeating.

Editor’s Note: In an ongoing series aimed at bridging the divide between policy analysis and academic scholarship, SAV contributors review recent articles and books published by leading scholars to evaluate the latest theoretical and analytical debates on strategic issues and their implications for South Asia. Read the series here.

***

Image 1: Nishant Vyas via Pexels

Image 2: Keystone via Getty Images