Twenty five years have passed since Pakistan and India clashed along the Line of Control in a limited terrain in what has come to be known, incorrectly, as the Kargil War. However, the misnaming of that armed conflict as “war” is not the only myth that has persisted for the past quarter century. There are other misperceptions too.

Coming just a few months after the overt nuclearization of India and Pakistan, the timing of the conflict raised concerns among international scholars and policymakers about the likelihood of a spiral that could bring nuclear weapons into play. Much has been made of this perceived nuclear angle to the conflict. The thesis has been promoted by analysts such as Bruce Riedel, a former CIA officer and policy expert, and Raj Chengappa, a veteran Indian journalist.

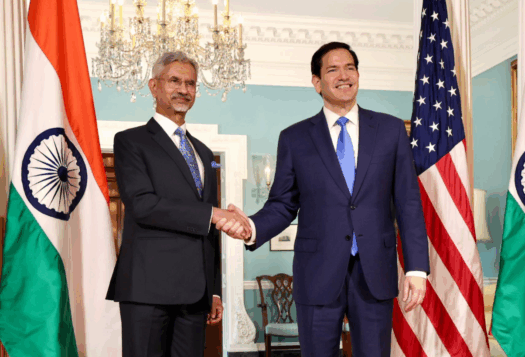

In his account of the meeting between then U.S. President Bill Clinton and Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif at Blair House in Washington, D.C. on July 4, 1999, Riedel states that Clinton told Sharif that his army was preparing for a nuclear war behind Sharif’s back and was shown satellite pictures as evidence of this contention.

To put Riedel’s account in perspective, India had carried out a second test launch of Agni-2, a medium-range ballistic missile, in April 1999 while Pakistan conducted the second test of the Ghauri missile, also a medium-range ballistic missile, a week later. Pakistan also followed this up two days later with the first test of the land-based, short-range Shaheen-1 ballistic missile. The satellite photos that Riedel has written about were most likely about the movement of these systems to the areas utilized for test launches. If Clinton did discuss these photos with Sharif, as Riedel claims, the U.S. intelligence might have mistakenly interpreted this as the operational deployment of these systems in their possible launch areas or Clinton might just have used these to pressurize Sharif.

The Kargil operation was conceived as a localized, tactical operation aimed at capturing a few Indian posts vacated by the Indian forces during the winter months. The objective was to observe and interdict the Srinagar-Leh highway in the Kargil region to make re-supply and reinforcement of Indian forces deployed in Siachen a tenuous exercise.

The missiles — the main delivery vectors of the two sides — had neither been proven nor inducted into the strategic forces at the time since they were still undergoing the testing phase. The only possible nuclear delivery systems available to the two sides at the time were their nuclear-capable aircraft. Though India made limited use of its air force, Pakistan did not deploy its air force throughout the conflict.

General V.P. Malik, India’s army chief during the conflict, has termed Reidel’s account as “highly exaggerated”[1] while Lt-General Khalid Kidwai, Director-General of Strategic Plans Division at the time, was dismissive of Reidel’s insinuations.

The late General Pervaiz Musharraf clearly stated in his memoirs In the Line of Fire that Pakistan’s nuclear capability was not operationalized at the time so contemplating any role for nuclear weapons in the conflict was out of the question.

The clashes were confined to a small segment of the Line of Control, and the volume of forces involved did not make a compelling case for either side to escalate to the nuclear level. Part of Pakistan’s Force Command Northern Area (FCNA), equivalent to one infantry division, comprising paramilitary Northern Light Infantry troops was the only formation taking part in the operation with support from mujahideen.

India did saturate the area with nearly five divisions and brought in all its Bofors guns, which were used in a direct fire role. However, India was careful to avoid opening another front. The navies didn’t engage in any hostilities while the bulk of the two armies, including the strike corps, were neither mobilized nor operationally deployed. By no political or operational definition of “war” can Kargil be called a “war.” At best, it was a limited conflict confined to Kargil, Dras, and Batalik.

Related to the nuclear dimension of Kargil is the argument that Pakistani planners intended to exploit the newly-introduced nuclear factor to their advantage by undertaking the operation under the nuclear overhang, confident that it would curtail India’s conventional response options for fear of nuclear escalation. However, facts belie this. The conflict took place too soon after the nuclear tests and their respective nuclear doctrines were still evolving, and nuclear capabilities were also limited in terms of numbers and variety of warheads. The nuclear command structures, too, were not in place.

On the Indian side, the army was caught unprepared, and its ammunition stocks ran low, as many analyses, including the Kargil Review Committee Report have, noted. India also chose, while seeking to reoccupy heights lost to Pakistan, to rely on coercive diplomacy through international state actors, especially the United States.

Another important point needs to be flagged. The operational plan for Kargil had reportedly existed since the late 1980s and was designed to cut off the supply lines to Indian troops in occupation of Siachen since 1984. As a former Indian brigadier Surinder Singh, who commanded the Kargil brigade during the conflict, has written: Pakistan had captured Point 5108, Dalunang Bunker Ridge and Sangruti heights in the Kargil sector in the 1980s. There was nothing unusual about these actions since India too undertook many such shallow ingresses along the LoC in the Dras, Qamar and Mushkoh sectors in addition to the occupation of the Siachen glacier area.

Be that as it may, the Kargil operation was conceived as a localized, tactical operation aimed at capturing a few Indian posts vacated by the Indian forces during the winter months. The objective was to observe and interdict the Srinagar-Leh highway in the Kargil region to make re-supply and reinforcement of Indian forces deployed in Siachen a tenuous exercise. However, as the Northern Light Infantry (then a paramilitary force) troops occupied their respective posts, they were tempted to move further into the unoccupied spaces beyond their assigned objectives, increasing the scope of the operation.

Another aspect of Kargil revolves around the identity of the forces occupying the Indian posts. The Indian high command initially characterized the assailants as a small group of mujahideen (local Kashmiri insurgents) who could be dislodged without much difficulty. This perception led to heavy casualties among the first waves of Indian counterattacks. However, after being unable to evict them, the Indians changed the narrative to mujahideen supported by regular Pakistan army troops and later to Pakistan army soldiers supported by mujahideen. Pakistan, however, officially stuck to the mujahideen narrative till the end. Though, later, General Pervez Musharraf in his autobiography mentioned the employment of 5 NLI battalions (a second line force at the time) in support of the mujahideen and also talked of the establishment of outposts and carrying out of raids and ambushes. He also revealed bringing in troops from elsewhere in the sector to augment Pakistan’s own defensive positions on the LOC. He has also remarked that the Indians lodged brigade-size attacks against posts held by as few as eight to ten of “our men,” leaving it ambiguous about what exactly he meant by our men.[2]

There is urgent need for independent, unbiased and objective accounts of the conflict based on serious research and analysis of actual records, as and when those are declassified.

Pakistan has been criticized for initiating the Kargil conflict and thereby creating the risk of a nuclear conflagration in South Asia. However, India, too has repeatedly tried to change the facts on the ground in Kashmir. A recent book by Indian scholar Happymon Jacob entitled Line on Fire: Ceasefire Violations and India-Pakistan Escalation Dynamics reveals the contours of an Indian plan to launch an operation far bigger in scale than Kargil along the whole length of the Line of Control from Batalik in the North to Chamb sector in the South aimed at capturing 25-30 Pakistani posts in battalion-to brigade-size offensive operations. Surprisingly, such a large-scale operation was considered by Indian military leadership as a limited operation that would remain below Pakistan’s nuclear threshold.

The operation, codenamed Operation Kabaddi, was planned to be executed anytime on or after September 1, 2001. It was never executed because of 9/11, which completely transformed the regional and global geostrategic environment. One cannot be sure whether the plans for Operation Kabaddi have been assigned to the dustbin of history or the files containing the plan are still lying in some archival record from where they could be retrieved, dusted and activated again. One could only hope that enough time has lapsed for the Indian decisionmakers to seriously contemplate the dangers inherent in such ambitious schemes.

Given the fact that there are so many conflicting narratives, myths and misperceptions surrounding the Kargil conflict, it is extremely difficult to arrive at a definitive conclusion due to non-availability of classified information even after the passage of 25 years. Some comprehensive studies have been published, but these were written too close to the events. It may be time now to have a re-look and see the forest instead of the trees. The need for this arises especially since the existing narratives on Kargil are, in almost all cases, either written by or based on the interviews of officers who took part in the operation. Most of these accounts are either attempts to glorify their own role or to defend their positions if they were accused of dereliction of duty, thus generally lacking objectivity. There is urgent need, therefore, for independent, unbiased and objective accounts of the conflict based on serious research and analysis of actual records, as and when those are declassified.

One must not lose sight of the fact that the roots of the Kargil conflict lie in the festering, unresolved Kashmir dispute. However, instead of making earnest efforts to resolve the dispute through negotiations with all stakeholders, India took unilateral actions in what Pakistan officially refers to as Indian-Occupied Kashmir in August 2019. The abrogation of articles 370 and 35A has stripped the state of its special status and rekindled resentment and anger in the local Kashmiri populace. This simmering frustration risks leading to another clash of arms between India and Pakistan. This time around, with matured nuclear capabilities including battlefield weapons and India’s Cold Start Doctrine and concepts such as surgical strikes, the consequences could be catastrophic.

Also Read: 25 Years after Kargil: Assessing Pakistan’s Crisis Preparedness

***

Image 1: Gaurav Chaturvedi via Flickr

Image 2: bm1632 via Flickr (cropped)

[1] V.P. Malik, Kargil: From Surprise to Victory (Harper Collins India, 2006), pp. 228-229.

[2] Pervez Musharraf, In the Line of Fire: A Memoir (United Kingdom: Free Press, 2006), pp. 90-93.