Late on June 15, Indian and Chinese troops engaged in a deadly clash on a narrow mountain ridge in the Galwan Valley in eastern Ladakh while the Indian Army was trying to reverse a Chinese intrusion. The clash resulted in the death of 20 Indian soldiers, including a Commanding Officer, and presumably some Chinese troops as well, but China has not released any numbers. Over 10 days later, the exact details of what happened are still murky, with a web of statements from military and diplomatic-level meetings between the two sides as well as media reportage suggesting disengagement one day but escalation the next. However, what is reasonably clear is that this standoff, which began on May 5 and has now dragged on for almost two months, is arguably the most serious crisis in India-China relations in decades, and has the potential to reshape bilateral ties in the long term.

What is different about this crisis?

Beyond the widely cited reasons for the significance of this crisis such as registering the first casualties on the India-China border since 1975 and the scale and sophistication of Chinese moves in terms of both the number of troops and equipment as well as the probing of multiple points simultaneously, there are a few more reasons that deserve attention. One, China is now claiming territory in the Galwan Valley that India considers settled and as many analysts have pointed out, China did not include as part of its claims in 1959 or 1960. From New Delhi’s point of view, this likely seems ominous since it fits the pattern of Chinese territorial aggression both in India’s immediate neighborhood, as seen during Chinese attempts to control Bhutanese territory through road construction during Doklam, and the broader region, such as Beijing claiming sovereignty over the East and South China Sea by building artificial islands over the last few years. But more importantly, in the backdrop of persistent Chinese efforts to resist the demarcation and delimitation of the Line of Actual Control despite the border agreements it signed with India in 1993, 1996, 2005, 2012, and 2013 and Beijing now openly violating these agreements by indulging in force buildup and unilaterally changing the status quo on the ground, the current standoff renders any border understandings between India and China essentially meaningless and casts doubts about China’s broader intentions.

The ongoing standoff underscores the unraveling of the logic that has undergirded India-China ties since the late 1980s and early 1990s—i.e. if the two sides kept the border dispute divorced from the broader relationship, they could build stability and cooperation, which would in turn help resolve boundary issues.

Two, the ongoing standoff underscores the unraveling of the logic that has undergirded India-China ties since the late 1980s and early 1990s—i.e. if the two sides kept the border dispute divorced from the broader relationship, they could build stability and cooperation, which would in turn help resolve boundary issues. In the Modi era, this has been symbolized by the “differences should not become disputes” policy. However, at least three major border crises between India and China in 2013, 2014, and 2017 as well as a tense period for Delhi-Beijing ties when China vocally and repeatedly opposed India’s candidature for the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) as well repeatedly resisted Jaish-e-Muhammad chief Masood Azhar’s designation as a global terrorist at the UN suggest this approach is not working.

Three, there has already been a hardening of Indian public discourse on China in the aftermath of Beijing hiding information about the severeity and spread of COVID-19, with anti-China memes and cartoons circulating widely on Whatsapp groups and social media, and many Indians tweeting in support of Taiwan’s bid for the World Health Assembly. In addition, China’s often publicly obstructionist and confrontational stance against India in the last few years, as seen through the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ aggressive rhetoric during the Doklam standoff or Beijing’s consistent blocking of India’s NSG bid, compared to generally anodyne statements by Chinese diplomats in the past extolling the “Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence” have likely contributed to a negative image of China in India. In that environment, the killing of 20 Indian soldiers on the border in an uncharacteristically violent way by Chinese troops is not likely to be an easily forgettable public memory, which could increase domestic pressure on the government to be tougher on China. Public anger after the June 15 incident is already visible in the form of a grassroots movement to boycott Chinese goods to economically hurt the country and an Indian company developing an app called “Remove China Apps,” which was downloaded 5 million times.

How can this crisis impact India-China relations going forward?

The Indian strategic community has often suggested the China threat is manageable by touting the fact that no serious confrontations resulting in death have occurred on the India-China border since 1967. That that rubicon has now been crossed calls into question this understanding. This could trigger a reassessment of New Delhi’s China policy, as indicated by recent comments from Foreign Minister S Jaishankar and the Indian Ambassador to China Vikram Misri, and as analyst Tanvi Madan at the Brookings Institution has drawn attention to, already being called for by former Indian diplomats such as Shyam Saran, Nirupama Menon Rao, and Gautam Bambawale.

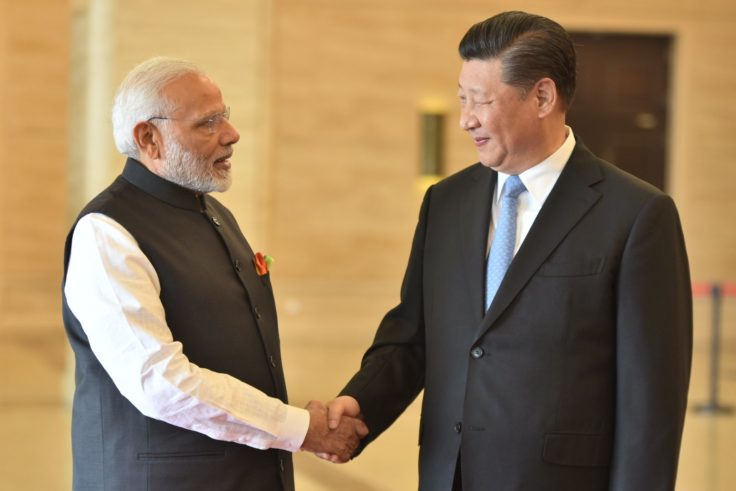

Particularly from the Modi government’s point of view, which has invested significant capital in engaging China, this is likely to be a crossroads moment. When Prime Minister Modi came to power in 2014, he tried to build economic cooperation with China, inviting Chinese investments in infrastructure in India. But even as President Xi Jinping pledged to invest USD $20 billion during his September 2014 visit to India, PLA troops intruded into Indian territory in Chumar. Modi then sought Chinese support for India’s NSG bid, and was spurned. After Doklam, he instituted high-level informal summits with President Xi to smooth over differences and come to a strategic understanding. However, any concessions India has made to accommodate the Chinese position, such as projecting an inclusive vision of the Indo-Pacific that would include Beijing or keeping Australia out of the Malabar exercises or downplaying the Quad, have not yielded results on issues that India cares about such as New Delhi’s concerns regarding the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor or the trade imbalance and market access issues between the two countries in China’s favor.

To be sure, the Doklam standoff had already rung alarm bells in Delhi that China was not only a long-term strategic threat but perhaps in the short to medium term as well. India’s move to join the revival meeting of the Quad in November 2017, a few months after Doklam, and its rapidly developing defense relations with the United States and Australia since then, should be seen in that context. Thus, the reevaluation of the threat China poses to India, which began after Doklam, is likely to be accelerated now.

In the end, the real test for India would be whether it seizes this strategic moment to learn the right lessons about China and sheds any presumptions of striking a grand bargain with Beijing.

A recalibration of India’s China policy in the long term may take several forms, such as strengthening partnerships with other like-minded countries to deal with the China challenge, both bilaterally and in plurilateral settings such as the Quad. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, India has already shown its willingness to utilize coalitions like the Quad Plus to find collaborative solutions to problems created by China. But it also may and is indeed already considering ways to reduce its economic exposure and dependence on China, both in response to this crisis and in the aftermath of coronavirus.

However, the challenge for India would be: is it possible to pave the path to comprehensive national power, particularly building economic strength to finance its military modernization, in order to deter Chinese adventurism without passing by Beijing’s doorstep? Analysts suggest that it would be difficult for India to become a USD $5 trillion economy without accessing Chinese capital. More importantly, how can India avoid serious conflict with China in the interim where it is still plugging the capability gap but is not quite there? These questions would require careful deliberation.

In the end, the real test for India would be whether it seizes this strategic moment to learn the right lessons about China and sheds any presumptions of striking a grand bargain with Beijing. As Stimson Center’s Yun Sun notes based on her conversations with Chinese strategists, there is little India can do to disabuse China of the notion that Delhi cannot be trusted or will not align with the United States. “It is only by recognizing change that we are in a position to exploit opportunities. The purposeful pursuit of national interest in shifting global dynamics may not be easy; but it must be done. And the real obstacle to the rise of India is not anymore the barriers of the world, but the dogmas of Delhi,” said Foreign Minister S Jaishankar in November 2019. Whether India sheds the dogmas in its China policy remains to be seen.

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

Image 1: Prime Ministerial Visits to China via MEA India

Image 2: PMO India via Twitter