Afghanistan remains a political and military conundrum for the United States, with victory elusive in the 16-year-old war. A recent report from the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) highlighted that the Taliban now exercises control or influence over 54 of the 407 districts in Afghanistan, going up nine districts from six months ago, showing that the insurgents have gained a lot of ground this year. While conceding more autonomy to his military commanders operating in Afghanistan, U.S. President Donald Trump identified India as a key partner in the administration’s new South Asia strategy, thus greatly expanding the scope and nature of their bilateral relationship in the region. For both these democracies, this strategy will help buy time for Afghan President Ashraf Ghani to tackle the “fifth wave of violence” in his country, but it will undoubtedly be tested by a resurgent Taliban and a challenging Pakistan.

India’s development assistance initiatives in Afghanistan remain popular and can be a vital arrangement in buttressing U.S. counterinsurgency plans to fight the Taliban. In fact, at a recent Senate Armed Services Committee hearing, U.S. Defense Secretary James Mattis referred to India-Afghanistan ties as “enduring,” a sentiment that reflects the U.S. trust in the utility of India’s goodwill in Afghanistan. As one of the largest regional and international aid donors to Afghanistan, India’s grant-based assistance work on critical infrastructure projects such as the Zaranj Delaram road, the Afghanistan Parliament building, and the Salma hydropower project have been viewed as symbols of progress, both within Afghanistan and internationally. More importantly, India’s capacity-building measures to train Afghan soldiers and civilian administrators have reinforced indigenous governing capacity in a way that is synergistic with recent U.S. pronouncements of its desire to push forward a peace process that is Afghan-led.

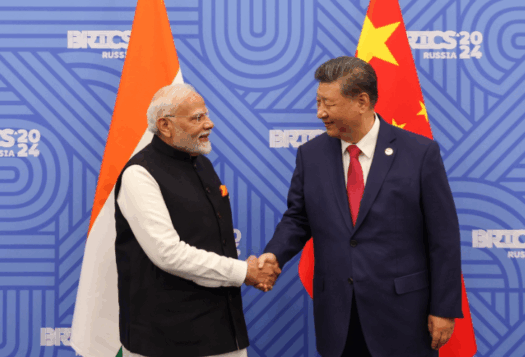

With the new U.S. strategy, India’s Afghanistan policy is likely to receive more support from the Trump administration. For instance, Indian External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj recently flagged off the first shipment of wheat to pass into Afghanistan through the India-constructed Chabahar port in Iran, bypassing Pakistani restrictions on India-Afghanistan overland trade. U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson’s manifold meetings with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi underline the new administration’s anxiety to prop India as a key regional player and encourage it to further flex its economic muscle in Afghanistan. During President Ghani’s visit to India last month, which happened to coincide with Secretary Tillerson’s visit, India announced a New Development Partnership with Afghanistan in the form of 116 projects across 31 Afghan provinces. For Ghani, the coming together of these two democratic powers is a “game-changer”—one that grants him a vantage position to attempt and push through a peace deal with the Taliban.

However, the current optimism around this strategic alignment will likely be moderated by highly-charged India-Pakistan-Afghanistan dynamics. In June, Afghanistan blamed Pakistan for a deadly suicide attack in Kabul and admonished Islamabad for merely paying lip service to counterterrorism efforts. Tensions between Pakistan and Afghanistan over terrorism will likely escalate due to a border fencing project that Pakistan has undertaken along the Durand line. Meanwhile, Pakistan’s (in)action against terror networks such as the Haqqanis are increasingly sapping U.S. patience in South Asia, and Secretary Mattis discussed with his Indian counterpart the symmetry between the United States and India towards a defiant Pakistan’s support for terrorism. Furthermore, this growing Indo-U.S. bonhomie in Afghanistan under the Trump administration has already rattled Pakistan’s decisionmakers. Pakistan’s intensifying regional isolation in South Asia could prove counterproductive to bringing about a solution to the Afghan conflict by heightening scrutiny of India’s actions in Afghanistan and helping usher China—Islamabad’s all-weather ally—into the subcontinent through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

Given the United States’ desire to resolve the conflict in Afghanistan swiftly, Ghani will continue to search for suboptimal solutions involving peace talks with the Taliban. In all likelihood, attempts to broker a peace deal with the Taliban will find support among an international community that needs a face-saving exit. Already, last year, Ghani struck a peace deal with the notorious leader of the Hizb-e-Islami group, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, while granting him and his followers full political rights. Earlier this year, Ghani sought to enlist the leader of Jamiat-Ulema-e-Islam (JUI-S), Maulana Samiul Haq, to parley with the Taliban. Ghani will solicit more Pakistani political leaders as negotiating partners as he tries to leverage an unreliable relationship with Islamabad. But reconciling the Taliban will pose a grievous test, considering the insurgent group’s renewed intention to transform Afghanistan into a “graveyard of the U.S. empire.”

India and the United States’ complementary approaches make them promising bedfellows in the Afghan reconstruction story. For both these countries, the high costs of Taliban recalcitrance will tie their interests together in the region for some time. At the same time, the strength of the India-U.S. axis will be tested by Pakistan’s distaste for Indian influence over its eastern border. The resilience of the Washington-New Delhi relationship will determine the success of Trump’s idea of victory in Afghanistan. In the short term, Afghanistan will benefit from an addition of U.S. troops and from India’s economic initiatives on the ground, but talking peace with a reinvigorated Taliban and a wary Pakistan could prove too tall a demand for President Ghani.

***

Image 1: Jim Mattis via Flickr

Image 2: Narendra Modi via Flickr