On February 26, 2019, India launched a brief but decisive airstrike on an alleged Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) training camp in Balakot, a town in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province. The strike was in response to the major terror attacks in Pulwama of Jammu and Kashmir that claimed the lives of 40 Indian security personnel. Reports on the results of the airstrike were often muddled and differed from source to source, but one thing was clear: the incident and Pakistan’s tit-for-tat airstrikes soon after fueled a dramatic crisis between New Delhi and Islamabad. The episode significantly raised concerns about a potential escalatory armed conflict and even a full-blown war between India and Pakistan. Though a spiraling military conflict was narrowly avoided, there have since been controversies over the implications of the unique cross-border operation.

Conflicting Narratives

As per New Delhi’s post-Balakot narrative, the airstrike set a “new normal” to address terror attacks emanating from inside Pakistan’s territory through inflicting punishment on the perpetrators. For New Delhi, the strikes also broke the spell of Islamabad’s nuclear deterrence. However, doubt has been cast over New Delhi’s characterization of a “new normal” through the airstrikes, particularly given the clumsy use of brinksmanship by both sides in previous crises and Islamabad’s ambiguous approach to the nuclear option if it is overwhelmed by India’s conventional military might. Islamabad’s unexpected show of restraint after the Balakot strikes may also be explained away otherwise: for instance, Islamabad viewed the Indian Airforce (IAF)’s limited action as being offset proportionately by Pakistan’s conventional countermove and did not see the strike as surpassing the set low-bar for other forms of military deterrence. Noticeably, Pakistani military elites have not abandoned a habitual thinking that links defense to its nuclear arsenal and Islamabad’s persisting effort to develop tactical nuclear weapons offers a telling testament to this. And for India’s part, how to reliably operationalize its hyped-up “Cold Start” doctrine remains a question, which adds further uncertainty to the prospects for any Indo-Pak conflict. Thus, it seems inconvincible that any Pulwama-sort emergency in the future can be resolved by simply using an intrusive airstrike (or a land “surgical strike”) without a spiral of escalation and nuclear risk.

But the very finale of the crisis, regrettably, was hardly seen as the result of any intended and effective bilateral diplomacy. More importantly, without post-crisis diplomatic reinforcements, the underlying problems have remained, meaning a likely future crisis will reignite the fears of an escalating armed conflict.

With nuclear-armed neighbors, diplomacy must take precedence over military responses in South Asia, even if other options—such as flexing military muscles, taking the maximum pressure approach, or securing domestic political gains—might be lucrative in their immediate effects. Indeed, India had reasons to seek sympathy and support in the wake of the Pulwama attack, yet the goal of its crisis diplomacy appeared set to justify a subsequent transgressing strike, rather than explore alternatives to remove its sense of insecurity. New Delhi’s disinterest in a diplomatic exit with Islamabad and decision to conduct a daring “preemptive” operation across the border also paid dividends to the ruling BJP’s domestic political needs. In retrospect, there would have been adequate space for the bilateral interaction before the airstrike occurred. Amid the international concerns following the terror attack, for instance, India could have taken advantage of a better position to timely push Islamabad’s stated willingness to cooperate and press for an enhanced action against anti-India militant outfits within its border.

In a rare moment of luck in the tense days following the airstrike, the crisis was eventually cooled after a mixed exchange of belligerent postures and conciliatory overtures between New Delhi and Islamabad, suggesting that the two nuclear-capable rivals never wanted to go to an all-out war. But the very finale of the crisis, regrettably, was hardly seen as the result of any intended and effective bilateral diplomacy. More importantly, without post-crisis diplomatic reinforcements, the underlying problems have remained, meaning a likely future crisis will reignite the fears of an escalating armed conflict. A future crisis may be even more threatening and consequential than Balakot, given the deep-rooted sources of conflict: the terror shadow haunting India for years, the rising nationalistic sentiments in both countries, and the deadlock of Kashmir as some underlying causes. The striking contrast of being prone to an interstate clash and lacking reliable crisis-managing platforms, either holistic or ad hoc ones, has been recognized as a dreadful reality in South Asia. Rather than scrambling in a crisis scenario, a worthwhile necessity for two South Asian rivals is to introduce a set of institutionalized and long-acting protocols to address each other’s sensitivities and stabilize their relations on a routine basis.

The Role of Third Parties: China and Crisis Mediation

Like previous Indo-Pak crises, the Balakot case once again underscored the relevance of third-party mediation in managing an unfolding crisis. In the backdrop of a lasting rivalry between the two nuclear-armed neighbors, a constructive role for international players seems indispensable in preventing a potential full-scale conflict. New Delhi’s wariness about any external leverage on its crisis with Pakistan, just like Islamabad’s interest in outside mediation—primarily due to an inevitable intent to draw external involvement to the disputed Kashmir issue—might not be beyond understanding from its own part, but that posturing has to be predicated on an expectable efficacy of bilateral crisis management. An appropriate external mediation, instead of being a game changer of the existing equation of force, may almost certainly serve as a booster of de-escalating conflict and returning to a diplomatic track. As a meaningful instance, the good offices of third parties, including one of China, turned out to be greatly helpful in defusing the 1999 Kargil conflict, a dangerous flare-up shortly following the nuclearization of the subcontinent. At the time China, alongside the United States, pushed Islamabad to withdraw its troops from Kargil and move toward a diplomatic solution, the key step for easing the mounting tensions and averting war. That was seen as a departure of China from its previous side-taking stance on a regional crisis.

China has defined its role in South Asian crises as a facilitator of peace and reconciliation, concerned about the protracted Indo-Pak tensions and potential for an escalatory conflict. Indeed, Beijing’s asymmetric engagement respectively with New Delhi and Islamabad may have an impact on its perception of a South Asian crisis. It is also true that the China-Pakistan strategic partnership has worked well; and that China’s ties with India have become increasingly sour in recent years, primarily due to the intense stand-off along their un-demarcated border. Nevertheless, the geopolitical alignments in the region are not the sole lens through which Beijing sees Indo-Pak tensions. This means China also intends to assess what has actually happened on its own merits before an apt policy choice calibrated.

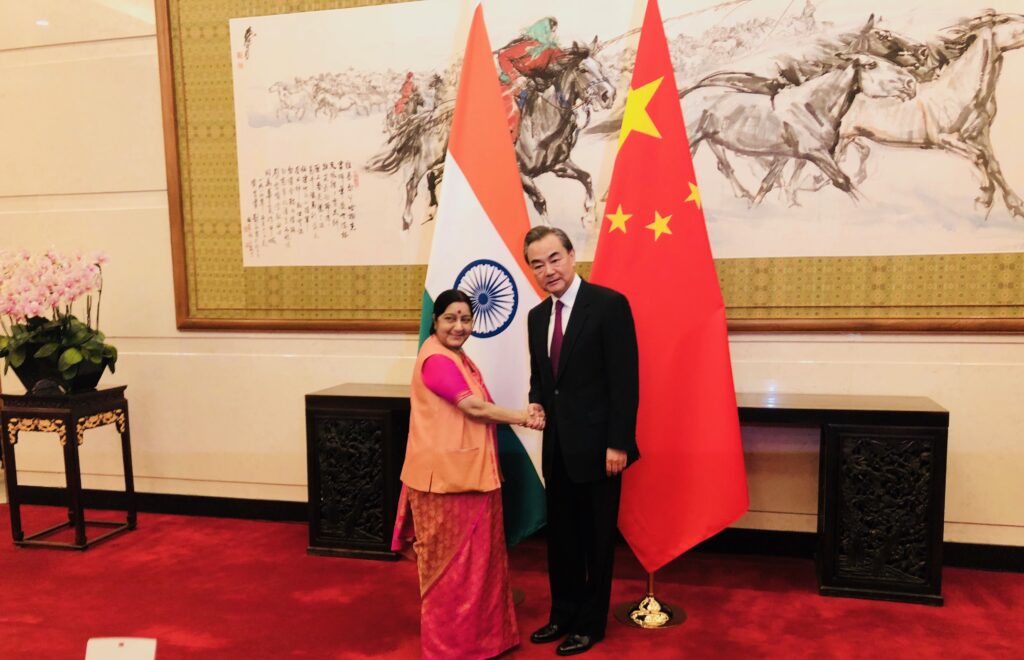

Unlike New Delhi, Beijing has recognized Islamabad’s endeavors, contributions and, of course, capacity limits in addressing terrorism. Around the Balakot incident, China’s balancing response proved to be an outcome of rational calculation: to react to the sudden crisis, Beijing condemned the terror atrocity in Pulwama and terrorism in a joint statement with United Nations Security Council, while urging New Delhi and Islamabad to exercise restraint, improve the bilateral ties, and embrace cooperation on terrorism. At the 16th Russia-India-China meeting in Wuzhen (Zhejiang) on February 27, Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi, joining his Russian and Indian counterparts, decried all types of terrorism and articulated rejection of extremist groups to be used for political and geopolitical goals. Soon afterwards in a call with Pakistan’s foreign minister Shah Mehmood Qureshi, who sought Beijing’s role of mediation, Wang stressed that “sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries should be respected,” an explicit criticism of India’s incursive airstrike. China’s stance on terrorism is expected to continue in South Asia today, with the growing concerns of terror threats (the most recent case is a deadly bus attack killing nine Chinese nationals in July 2021) and fears of a possible spillover of the regional militancy and jihadist ideology following the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan.

…The geopolitical alignments in the region are not the sole lens through which Beijing sees Indo-Pak tensions. This means China also intends to assess what has actually happened on its own merits before an apt policy choice calibrated.

After the fallout from Balakot, Kashmir remains the flashpoint of Indo-Pak relations and will continue to foster an unstable regional security landscape. In light of this rationale, there have been justifiable worries about the implications of India altering the legal status Indian Administered Kashmir. This, along with other measures such as the controversial Citizen Amendment Act in 2019, which would further complicate the vexed relations between India and Pakistan, have signaled New Delhi’s hardline approach in domestic and external politics while, at the same time, have prompted Islamabad’s sharp response and the skepticism elsewhere. In this sense, the crux of the matter for avoiding another critical crisis from spiraling into a military showdown between India and Pakistan—as well as addressing and removing the menace of terrorism—still lies with a significant improvement of their bilateral relations based on credible trust building efforts. In a broader context, the changing regional scenario will also be substantially influenced by multiple outside inputs, ranging from the closer Indo-US strategic engagement, the estrangement between Pakistan and the United States to the sustainable China-Pakistan partnership alongside an uncertain trajectory in Beijing’s relations with New Delhi. Any chances of China-US coordination in managing South Asian crises, akin to the erstwhile Kargil, will hinge on the nature of the bilateral relations between Beijing and Washington.

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a four-part series featuring reflections from senior analysts and policymakers in the United States, India, Pakistan, and China on the lessons learned from the 2019 Pulwama/Balakot Crisis. Read the full series here.

***