In August 2017, over 745,000 Rohingya began fleeing Myanmar’s Rakhine State to Bangladesh. Now, more than two years later, Cox’s Bazar is the largest refugee camp in the world. Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina recently described the situation as “untenable,” but prospects for a quick resolution remain elusive.

The government of Bangladesh maintains that repatriation to a safe environment must be the solution, and Myanmar has stated that it is already prepared to receive returnees. However, international organizations, various foreign governments, and the refugees themselves have expressed concern that conditions in Myanmar are not conducive to a safe, dignified, and sustainable return.

History of Exodus

International organizations, foreign governments, and the refugees themselves have expressed concerns that conditions in Myanmar are not conducive to a safe, dignified, and sustainable return.

In August 2017, a Rohingya insurgent group, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, attacked several police posts, killing twelve security officials. The Myanmar military, known as the Tatmadaw, responded by conducting counterterrorism clearance operations in Rohingya villages. Brutal reports of state-sanctioned arson, rape, and killings of thousands of civilians (conservative estimates say 10,000) followed. Over 745,000 Rohingya fled to Bangladesh, joining tens of thousands more who fled earlier waves of violence in 2016 and 2012.

Myanmar has denied accusations of human rights abuses, stating that the military responded legitimately to threats posed by Rohingya militants. However, a UN-commissioned report accused the Tatmadaw of acting with “genocidal intent,” and the UN human rights chief described the situation as a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing.”

The Rohingya, labeled the “most persecuted minority in the world,” have faced generations of systematic discrimination. A distinct, majority-Muslim ethnic group, they trace their roots in Rakhine State to well before the Burmese Empire conquered the land in 1784. The Burmese government, however, views the Rohingya as illegal Bengali immigrants, “outsiders,” or “invaders.”

Consequently, Rohingya have been subject to forced labor, land seizures, restrictions on freedom of movement, and denial of education and employment. Most significantly, Myanmar’s 1982 Citizenship Law grants citizenship based on membership in one of 135 recognized ethnic groups. The Rohingya, excluded from the list, have been stateless since.

For some in Cox’s Bazar, this is their third time as refugees. 200,000 Rohingya fled abuse into Bangladesh in 1978, following a military operation to register citizens and prosecute illegal immigrants. In 1991, operations picked up once again—this time, under the premise of targeting Rohingya Muslim extremists. 250,000 Rohingya poured into Bangladesh, recounting forced labor, rape, extrajudicial killings, and torture. In both cases, the majority of refugees returned to Myanmar through what many human rights organizations considered a premature, unsafe, and involuntary repatriation process

The Question of Repatriation

Following the most recent exodus, Myanmar and Bangladesh signed a bilateral repatriation agreement in November 2017. Both countries have also signed Memorandums of Understanding with the UN refugee agency, UNHCR, codifying principles of “voluntary, safe and dignified” return. These agreements are strikingly similar to those that predicated the repatriation of the 1990s—in some cases, verbatim.

The governments have twice tried – and twice failed – to begin repatriation, once in November 2018 and again in August of this year. The refugees refused to go, saying they would not return without guarantees for their safety and citizenship.

Currently, such guarantees appear far-fetched. The UN’s Fact Finding Mission released a report in September stating that the over 600,000 Rohingya still in Myanmar remain under “serious risk of genocide.” The BBC has reported widespread destruction of Rohingya villages; where homes once stood, satellite images show confinement camps or government facilities. Refugees still enter Bangladesh daily. Since January, new conflict has erupted between the Tatmadaw and the Buddhist ethnic Rakhine population. Conditions in Rakhine State have not improved; they may have deteriorated.

As for citizenship, Rohingya returnees would instead receive National Verification Cards. NVCs effectively solidify the Rohingya’s status as foreigners in Myanmar, and human rights organization Fortify Rights has described the cards as “tools of genocide.”

Yet in the face of continued international scrutiny, Myanmar has encouraged the UN to spend less money on investigating alleged human rights abuses, and more on expediting return. But as long as the international community and the refugees themselves remain skeptical of conditions in Rakhine State, repatriation is unlikely to move forward.

Heightening Domestic and Regional Concerns

Rohingya have been subject to forced labor, land seizures, restrictions on freedom of movement, and denial of education and employment. Excluded from Citzenship Law list, they have been stateless since 1982.

Even if repatriation were to begin this year, analyses estimate that completing returns would take over ten years. That is to say, the vast majority of the refugees will likely stay in Bangladesh for the near future.

Bangladesh has been gracious in accepting hundreds and thousands of refugees, but patience is wearing thin. Local communities blame refugees for illegally taking lower-paying jobs and worry about the uptick in crime rates. Not wanting to encourage refugees to stay, Bangladesh has forbidden employment and formal education for Rohingya.

Conditions in Cox’s Bazar are crowded and desperate. Ninety-seven percent of children aged 15 to 18 are not receiving any education. Gangs and militants are increasingly operating in the camps. Refugees, barred from the economy, are turning to illicit activities. Drug and human trafficking are rampant.

There are growing anxieties about regional consequences, too. Hasina has expressed fears that refugees are susceptible to radicalization. Though transnational groups like ISIS or al-Qaeda are not believed to have influence in the camps, a Bangladeshi hardline group, Hefazat-e-Islam, has called for jihad against Myanmar and is present in the camps’ mosques and madrasahs, or Islamic schools.

In response to growing security concerns, Bangladesh has planned to enclose the camps in barbed-wired fences and has cut cell-phone access. The government also wants to move 100,000 refugees to Bhasan Char, a remote island in the Bay of Bengal, until they can be repatriated. Human rights organizations have expressed concerns that the island is flood-prone, uninhabitable, and would isolate refugees. Bangladesh insists that they are making the necessary preparations. No Rohingya have relocated yet.

Looking Forward

Hasina has stated that the refugees can stay for now, but the situation will only get more desperate as international aid and attention wanes. Currently the UN’s 2019 Joint Response Plan for the humanitarian crisis is only 42.9 percent funded.

Myanmar, coming up on elections in 2020, may become even less willing to create conditions conducive to repatriation. The Rohingya’s return is broadly unpopular among the ethnic Bamar majority and the ethnic Rakhine and likely to be politicized.

The present intractability of the situation places the burden on Bangladesh and leaves the Rohingya in limbo. As one UN official in Cox’s Bazar noted, “if policies are not created in recognition that this is a long-term problem, things are going to get worse.”

***

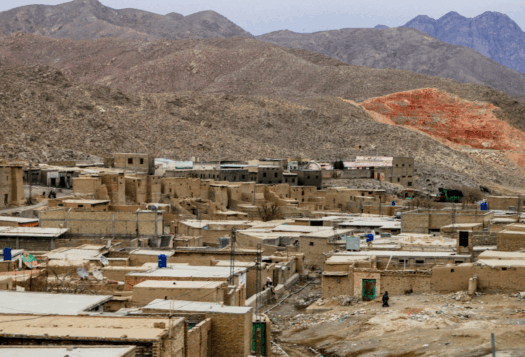

Image 1: Wikimedia Commons

Image 2: AFP Contributor via Getty Images