The 2014 general elections—regarded as the “First Social Media Election” in India’s political history—kickstarted a social media revolution in Indian politics. Before the 2009 general elections, Shashi Tharoor, a Congress MP who had previously served as UN Under-Secretary-General, was the only Indian politician with a Twitter account. All major political parties significantly expanded their social media footprints ahead of the 2014 elections.

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s success in mobilizing India’s digital generation using social media platforms has forced contending parties to revamp their social media engagement. As a result, millions of politically motivated messages now flood India’s digital space, making elections susceptible to social media manipulation. The BJP reportedly operates around 200,000 to 300,000 WhatsApp groups and controls 18,000 fake Twitter handles. The party has developed an effective IT wing linked to disinformation and propaganda, both of which it uses to stoke communal divisions to reap electoral benefits. The spread of disinformation, and polarizing, BJP-led social media campaigns promoting Hindutva, deepen tensions among Hindu and Muslim communities. These combined threaten truth and India’s secular-democratic fabric.

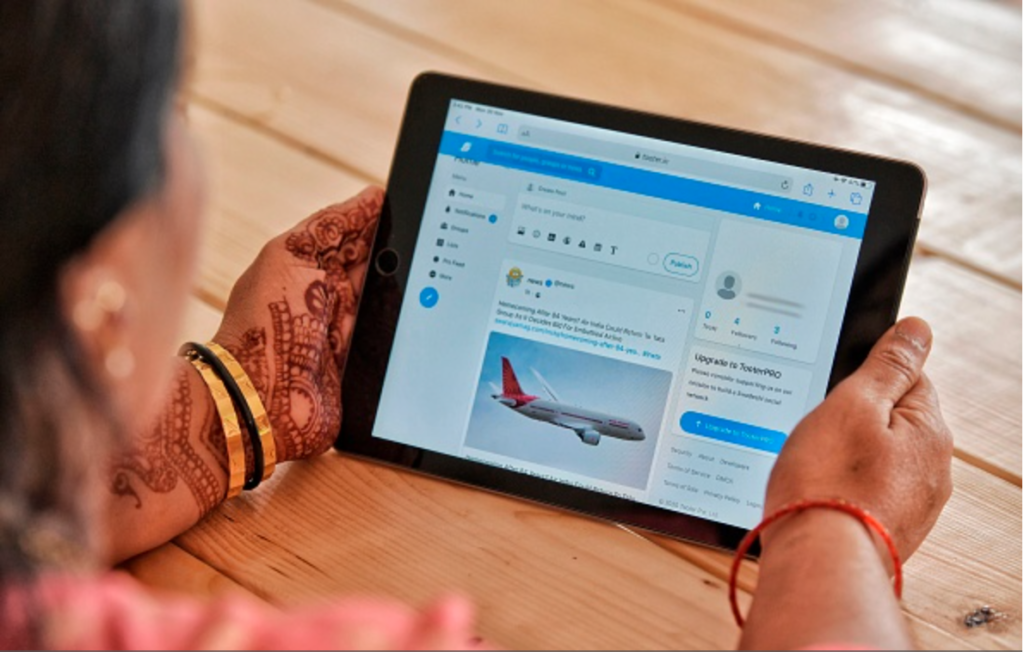

Widespread Political Messaging on Social Media

According to the Government of India, social media users in the country have surpassed the 500 million mark, with WhatsApp, YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter claiming 530, 448, 410, 210, and 15 million users respectively. According to the 2017 CSDS-Lokniti survey, one-sixth of India’s WhatsApp users were part of a WhatsApp group either managed by a political party or its leader. Signifying the volume of politically motivated content, a 2019 CSDS-Lokniti, and Konrad Adenauer Stiftung survey determined that one in every three Indian citizens on social media consumes political content daily or regularly.

The BJP has developed an effective IT wing linked to disinformation and propaganda, both of which it employs to stoke communal divisions to reap electoral benefits.

Political content voters absorb through WhatsApp and other platforms influences political perceptions in a two-step manner. First, political accounts generate an influx of positive narratives concerning a party, drowning out criticism. For instance, widespread nationalist content from BJP-affiliated right-wing groups praised the army and the Balakot air strikes while evading content on rising unemployment and debilitating economic crises in India. Second, disinformation—spread particularly through fake-social media handles—consolidates nationalist support against perceived “enemies.” In early 2020, BJP IT wing head Amit Malviya tweeted a fake video of Anti-CAA protestors raising “Pakistan Zindabad” banners. This was intended to deepen Hindu-Muslim communal divisions and advance the BJP’s political efforts.

The Evolution of Social Media in Electoral Politics

The BJP’s social media campaign has evolved significantly since 2014: then it largely focused on highlighting its leader; now it seeks to control content citizens consume. The core focus of BJP’s social media campaign in 2014, aided by professional agencies, was building the brand of then Prime Ministerial candidate Narendra Modi, promoting its development agenda and criticizing the ruling Congress government. Indicating the effectiveness of BJP’s social media strategy, Modi surpassed Tharoor as the most followed Indian politician on Twitter in 2013. The BJP’s social media campaign adopted more polarizing methods in the 2017 Uttar Pradesh assembly elections and the 2019 general election after the BJP government failed to deliver on its electoral promises, including its leading development campaign.

The BJP’s savvy social media presence and electoral success has created incentive for other parties to expand their presence in the digital space. Faced with continuous electoral setbacks since 2014—and a tarnished image of leader Rahul Gandhi as “Pappu” (a mocking name for an immature and half-wit boy in popular media) by the BJP IT cell—Congress’ social media spending increased tenfold in 2019 compared to 2014. Even the Communist parties, which have a history of opposing computerization, have begun training their cadres.

Weaponizing Hindutva

As the BJP has taken advantage of the social media space, Hindutva has emerged as the central rallying point of its disinformation campaign. As per 2018, disinformation in India centers on four themes linked to Hindu nationalist ideology: “Hindu Power and Superiority, Preservation and Revival (Hindu Culture), Progress and National Pride, and Personality and prowess of Narendra Modi.”

The BJP has used “anti-national” messaging to delegitimize the recent farmers’ protest, unmasking its weaponization of digital platforms to thwart voices of dissent. As part of this, the BJP has attempted to portray protesting farmers as “Khalistan supporters.” In November 2020, BJP IT head Amit Malaviya shared a video on Twitter countering the allegations of police brutality against protesting farmers. Later, Twitter flagged this video as “manipulated.” Then, a host of BJP leaders—including Tajinder Bagga (BJP Delhi spokesperson), Varun Gandhi (BJP MP) and Harish Khurana (Delhi BJP spokesperson)—propagated disinformation and tied protesting farmers to the Khalistan movement.

A significant part of the success of BJP’s social media strategy has been its ability to propagate messages that are more personal and thus have greater potential to influence a wide range of citizens’ political perceptions.

People are more likely to believe fake news when it aligns with their existing beliefs. The more personal the content becomes, the greater the impact it has on voter thinking. A significant part of the success of BJP’s social media strategy has been its ability to propagate messages that are more personal and thus have greater potential to influence a wide range of citizens’ political perceptions. To maximize the impact on voters’ mindset, the BJP, with the assistance of professional agencies, creates digital content in local languages and makes use of memes from popular shows and movies. For instance, it employed trolls and campaign ads using memes from the Game of Thrones series. Ample financial resources to set up IT cells, recruit techies, and hire professional agencies— combined with an efficient and vast network of organizational machinery on the ground to ensure the social media campaign reaches ordinary voters—helped the BJP far surpass competing parties in the digital outreach.

Conclusion: Impact on Democracy

Only a small proportion of Indian voters are social media users at present yet with a huge spike in social media users each year, social media’s role in political communication will only grow in upcoming years. The BJP has been the primary player accelerating the social media revolution in Indian politics. Campaigns intended to polarize on social media add fuel to the religious and social tensions in different parts of India, even generating threats to national security. Though the BJP’s social media campaign is an extension of what it does on the ground, using fake IDs to spread hate messaging makes BJP’s social media weaponization even more dangerous as it evades accountability and social auditing and offers easy deniability.

As the BJP seeks to advance its Hindutva agenda, the digital space is its most fertile ground. Since government-imposed censorship of social media platforms under BJP could be —used to crush voices of dissent—establishing an independent body, able to resist the government intervention, is the most feasible solution. Although ruling BJP may not support constituting such an independent body, the opposition parties must pressure the government for such a reform through all available means, including by seeking judicial intervention. Opposition parties must play an active role in holding the BJP accountable in its use of digital platforms. The social media platforms themselves must more effectively resist the pressures from government, halt the spread of disinformation, and work to guarantee the platforms do not become a vehicle for social and communal polarization.

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

Image 1: Bloomberg via Getty Images

Image 2: Manjunath Kiran/AFP via Getty Images